Have you, like me, been wondering what U.S. “climate czar” John Kerry has been talking about with his hosts in a Beijing that, like much of China and the United States, is drenched in extreme weather events?

If you read the (uber-nationalist) New York Times account of the meetings, you’ll learn that Kerry lectured and hectored his hosts. The Washington Post account was more measured, starting as it did with this lede:

John F. Kerry praised China’s “incredible job” expanding renewable energy sources Monday, while urging the world’s largest greenhouse gas emitter to stop building coal-fired power plants.

Let’s hope that Kerry’s approach toward his hosts was indeed respectful and collaborative. The fate of humankind and our whole, deeply troubled planet hangs on these two mega-powers finding ways to work together to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, while also reining in the currently raging over-depletion of all of our planet’s material resources.

If these two governments cannot overcome, or set aside, their political differences and find a way to work together to reduce CO2 emissions and resource depletion, then we will surely, within the next 20 years, see extreme weather events “baked” into all of the world’s climate system. We will also see entire economies, small and large, forced screeching to a halt—and also, all the social and political turmoil that will predictably result from that.

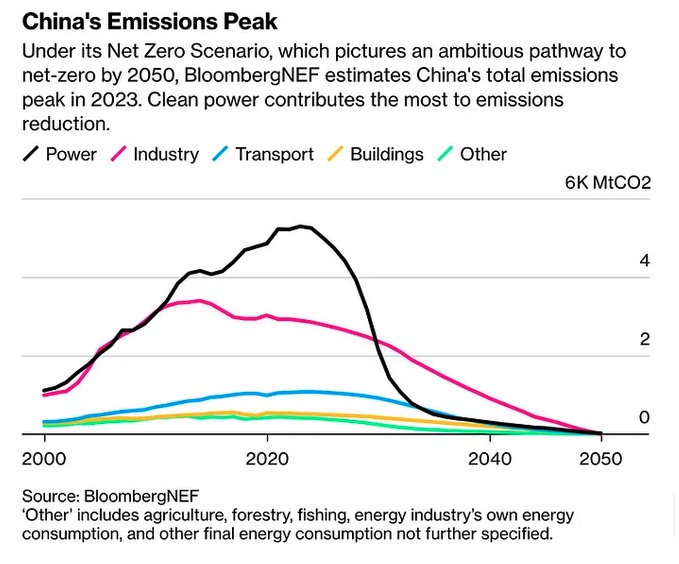

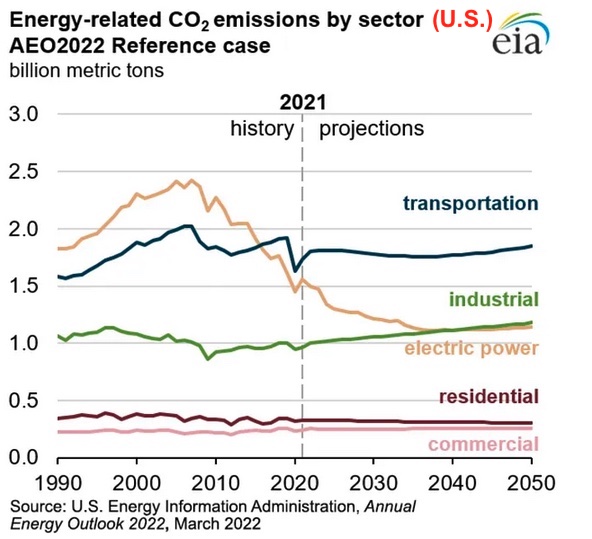

First, two key pieces of data regarding these two countries’ recent and projected CO2 emissions:

Click on either graph to expand it. The y-axes (verticals) show the same thing: billions of metric tons of CO2 emissions—but to different scales, as shown. The x-axes show past reported CO2 emissions levels through 2021 or 2022, and then projections from then through 2050.

See, most obviously, how China’s emissions, as reported by Bloomberg, are projected to drop to zero by 2050, while the United States’ emissions are projected by the federal government’s own Energy Information Administration, to show an increase between 2021 and 2050.

How is China planning to achieve its drop to zero by (or by some accounts, significantly before) 2050? And how can that plan be reconciled with the many reports we have of China continuing to build coal-fired power stations? A good explanation of both these points can be found in this report (PDF), which was recently released by the California-based NGO Global Energy Monitor (GEM).

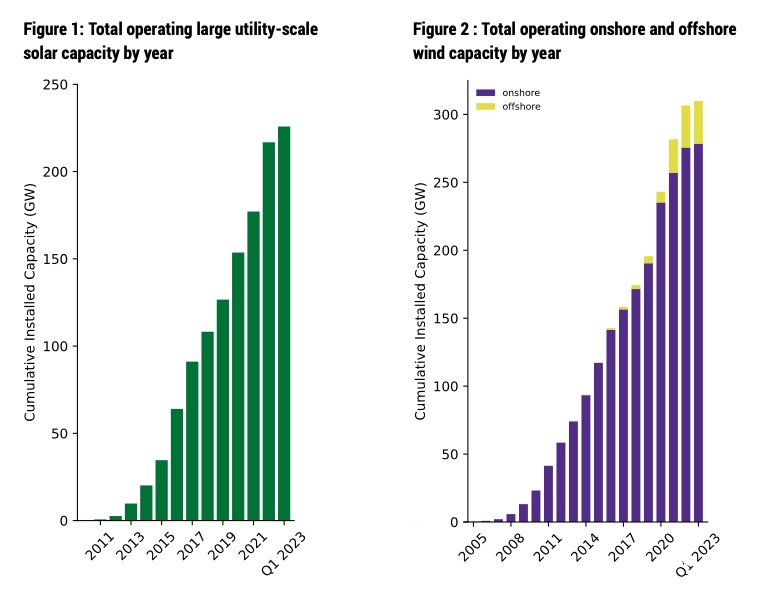

The GEM report, titled “Race to the Top: China 2023” has charts that show the stunning increase in the past 18 years of China’s capacity to generate electricity using both solar power and wind:

Actually, as the report itself states,this undercounts the total generating capacity in both fields, since it counts only the larger, “utility-scale” projects, whereas China also has many smaller projects. Hence, regarding solar, while the GEM chart shows only 228 GW capacity as of 2023Q1, the Chinese authorities report a total of 392 GW. Similarly, for wind generation, GEM reported 310 GW, while the Chinese government reported 365 GW.

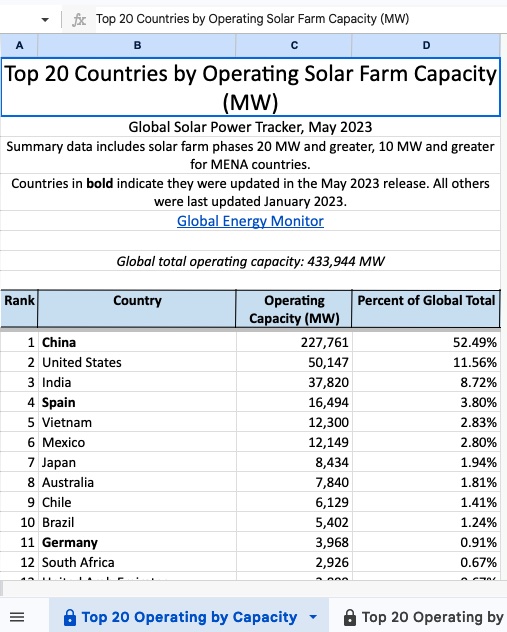

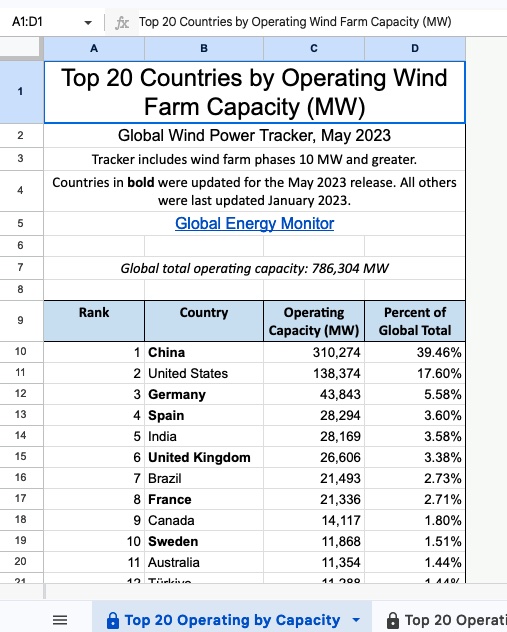

GEM’s website also provides a large amount of other energy-related data, including these notable, very up-to-date, country-by-country comparisons of clean power-generating capacity using solar and wind:

Regarding China’s continuing (and currently increasing) use of coal-fired power generation, the GEM report provides (pp. 20-23) many details on how the Chinese authorities are working to integrate cleanly generated power into a nationwide transmission system that also carries a lot of coal-generated power; to push coal-generated power increasingly into a “support” role to support the continued expansion of clean energy; to develop the power-storage systems needed to even out the variations of supply that clean energy generation results in; and to reduce their reliance on coal to zero over the coming decades.

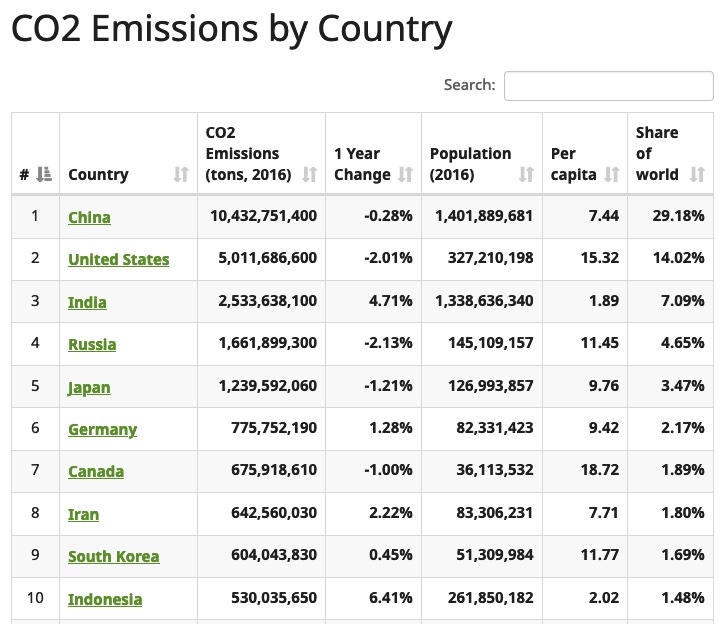

It remains true that, as of now, China’s annual rate of CO2 emissions is roughly twice that of the United States. However, since China’s population is roughly four times that of the United States, its per-capita rate of emissions is roughly half the U.S. rate.

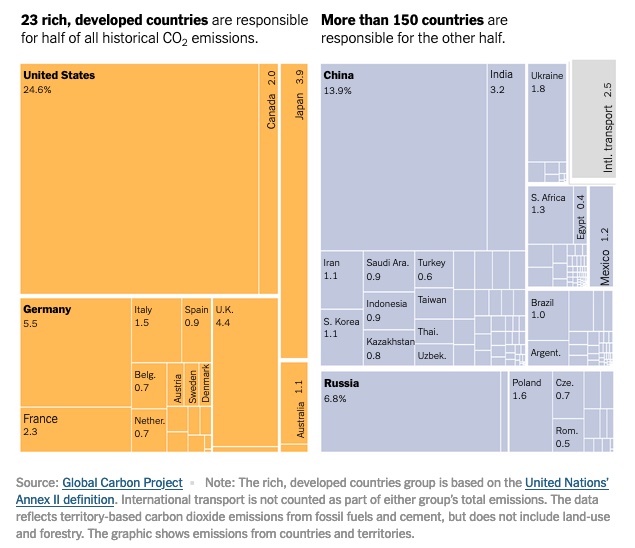

There is also the matter of the responsibility of various countries for historical emissions of CO2, that is, since the start of the Industrial Revolution. These figures from the Global Carbon Project (via the New York Times) show the estimated total historical CO2 emissions of different countries through 2021:

This question of “historic responsibility” for the long accumulation of GHGs in the atmosphere, with China’s historic responsibility pegged at just over half that of the United States, is relevant to China’s continuing claims that, as a country that is still developing, it does not have the same responsibility as the United States and the other “rich, developed” countries for bearing the costs of global climate-mitigation efforts. On Sunday, U.S. National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan hawkishly told CNN’s “State of the Union” that China, “should not able to hide behind any kind of claim that they’re a developing nation, to step up to their responsibility.”

John Kerry may sincerely want to work with his Chinese counterparts on joint plans to scale back GHG emissions and the broader global depletion of the Earth’s resources. But his boss, Pres. Biden seems determined to continue to needle, constrain, and confront China, so it is hard to see how much Mr. Kerry can achieve.

During his 30 months in office so far, Pres. Biden has not only kept in place the trade tariffs that Pres. Trump earlier imposed on China. He has also imposed a range of tough new curbs on China’s ability to develop its superconductor manufacturing capabilities. His Pentagon has identified China, for the first time, as the “pacing threat” or “pacing challenge” against which the U.S. military needs to plan and has increased the pace and scale of the surveillance and probing operations it maintains near China’s coastline. His administration has worked hard to strengthen military alliances with Japan, Australia, and South Korea and to find other eays to “contain” reach in the Asia-Pacicific region. And he has imposed a broad range of curbs on scientific cooperation between the two countries.

For its part, after the visit that Pres. Biden’s ally the former U.S. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi made to China’s near-secessionist province of Taiwan last summer, China responded by withdrawing from a number of longstanding U.S.-China consultation forums. More recently, it banned one U.S. company, Micron, from supplying microchips to critical Chinese industries. And it has announced a forthcoming ban on the export of gallium and germanium, two rare minerals vital to the manufacture of computer chips.

In general, relations between the two countries remain very tense, even after Secretary of State Anthony Blinken visited Beijing last month. Pres. Biden seems to have gauged the mood of the U.S. public as one very supportive of policies that constrain and counter China. That reading may be generally accurate, at a superficial level; and with Biden now well into the planning for his re-election campaign for next year, it is probably one he is very reluctant to buck.

However, it is also notable that Biden has done nothing at all to try to lead a broad conversation with Americans about the extreme risks of any escalation of tensions with China and the many benefits, from an economic, ecological, and global perspective of trying to find as many ways as possible to work with Beijing.

So where does this leave John Kerry and his current, climate-focused mission in China?

Kerry certainly does not look poised for any significant achievements, or breakthroughs. From the Chinese side, a team of reporters from the semi-official Global Times daily wrote that the four hours of meetings that Kerry held with his Chinese counterpart Xie Zhenhua on Monday,

are seen as the latest effort to revive climate cooperation between the two countries and a positive signal for bilateral relations, currently at a historical low.

With the topics of reducing methane emissions and coal use on the agenda, experts said that climate change cooperation is not an “ivory tower” or “safe house” for China-US relations, as the two sides face the complexity of “rivalry and cooperation”, “divergences and shared responsibilities.”

Washington claims to seek climate cooperation while maintaining its suppression of Beijing in areas such as trade and technology, and has been flip-flopping on climate policy under partisan politics, creating obstacles for China-US cooperation in this field, some experts said.

China is seeking substantial dialogue this week, and exchanges on climate and the green transition could contribute to improving China-US bilateral relations, Xie said on Monday…

Let us hope for the best. But let us also keep front and center in mind the sharp differences between the ways Washington and Beijing are already planning to address their countries’ contribution to CO2 emissions over the 27 years ahead.

3 thoughts on “John Kerry, China, and averting planetary disaster”

Comments are closed.