This schematic from CSIS traces the 2018 rail links between China, Russia, and the rest of Europe.

In the United States, relations between China and “the West” are viewed as a trans-oceanic affair, with the Asia-Pacific region forming its main arena of cooperation or competition. Viewed from Europe or West Asia (the area formerly known as the Middle East), relations with China look different: in recent decades the many land routes that crisscross Eurasia in all directions have been growing fast in length, connectivity, and capacity.

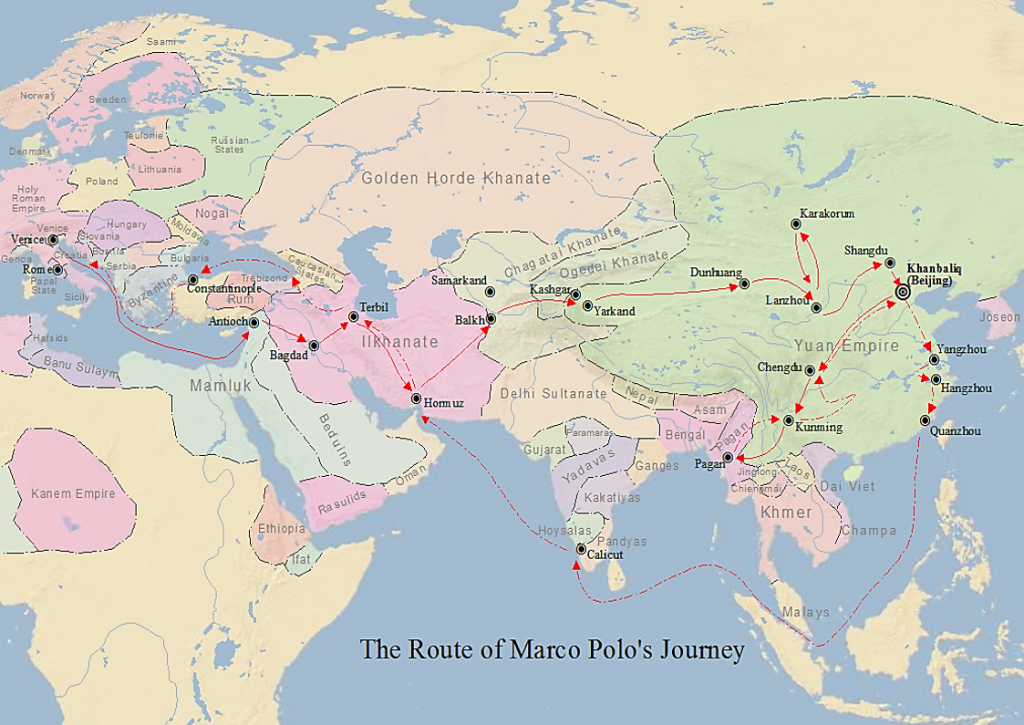

This could mark a big historical turning-point—or rather, a return after a 600-year hiatus to the kind of world in which, in the late 13th century CE, Marco Polo and his uncle traveled overland to, and through, large portions of China, as shown here.

In the intervening centuries, it was the lethal naval power of a handful of small West European states and their American offspring that came to dominate the destinies of all of humankind.

Everywhere they sailed in 15th through 20th centuries, those European-origined naval empires crushed the power of the large land-based polities they encountered. The Aztecs, Incas, Mughals, Ottoman, Ming and Qing Chinese, and numerous other empires and local confederations were all wiped out.

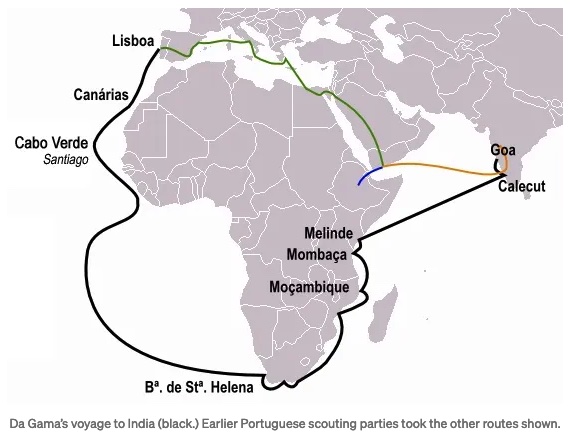

So now, 600 years after Portugal’s Prince Henry the Navigator first started to build his network of heavily armed trading posts along the coasts of Africa, it looks as if land empires and the ties that bind them are about to make a comeback.

Let’s look at some recent news stories. There was this NY Times story about the numerous European leaders who have been visiting, or are now about to visit, Beijing. “European leaders,” the story says, “have been making a beeline to Beijing, weighing their strategy toward China just as the United States intensifies pressure to pick sides in the growing acrimony between the two superpowers.”

Or, from West Asia, there was the slightly earlier news of China’s leaders pulling off the diplomatic coup of brokering a rapprochement between former foes Iran and Saudi Arabia.

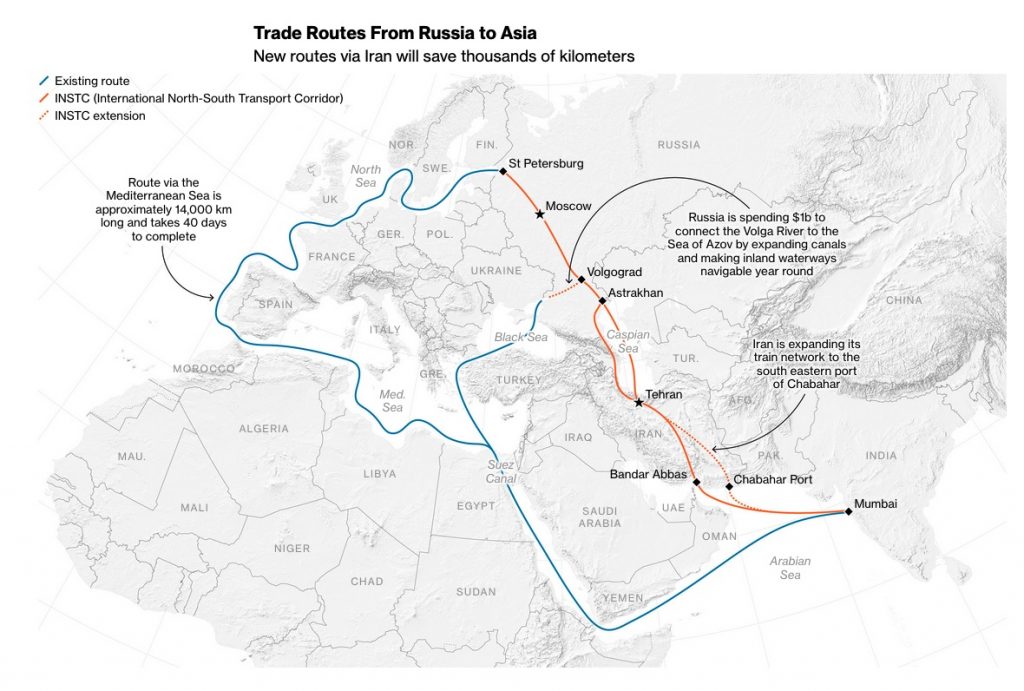

That latter news story can handily be supplemented with this recent (but paywalled) Bloomberg piece about China and Iran collaborating on upgrading a key rail corridor that connects Russia (and potentially, also other European countries) much more speedily with ports in the Indian Ocean than is currently doable…

A quick digression into rail nerdery

(If you don’t share my obsession with this topic, scroll on down for more of the geopolitics…)

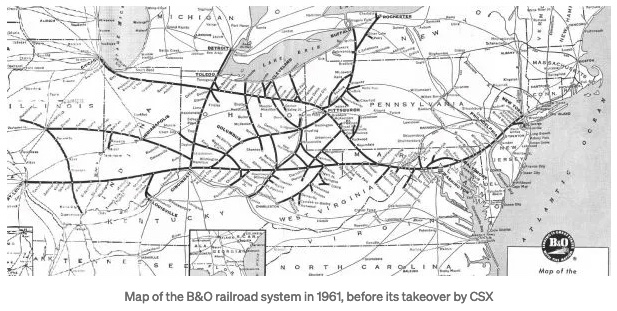

Ever since the 19th century railroads have been—along with pipelines—a key ingredient of land power. They were key for the Anglo settlers along the U.S. east coast who wanted to expand their colonies first across the Appalachians and soon after right across the content. In the aftermath of WWII, they were key for the project of the visionaries who wanted to end war in Western Europe by forming a European Union. And more recently yet, they have been key in the push by China’s leaders to spur growth in the whole of their large country while also integrating their economy with those of Central Asian nations and Russia (also known as the Belt and Road Initiative)…

Here’s a great map, from this 2016 story in the Financial Times (unpaywalled!) that shows the Central Asian part of this growth—for pipelines as well as rail lines:

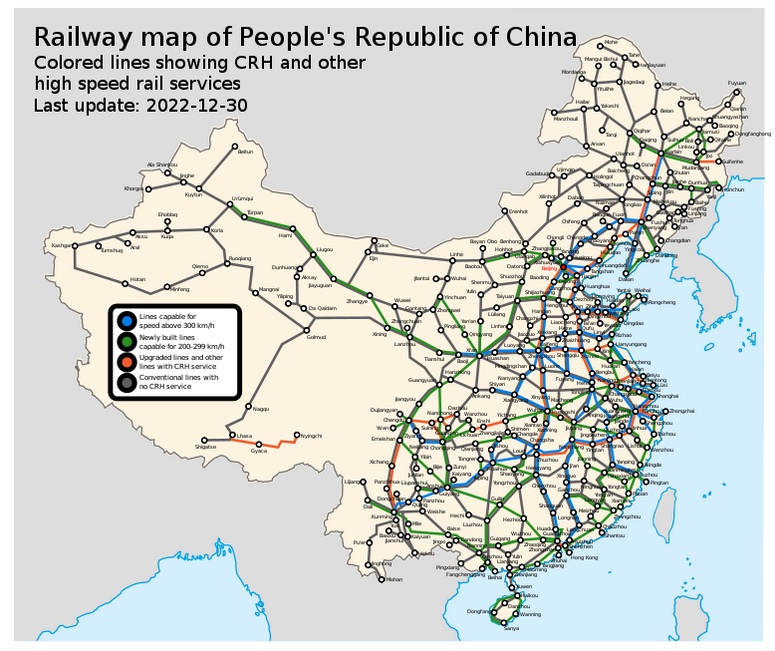

And here, for the map finale of this section, is a map from Wikipedia of China’s own domestic high-speed rail lines. (CRH is short for China Rail Highspeed):

Eat your heart out, Amtrak travelers!

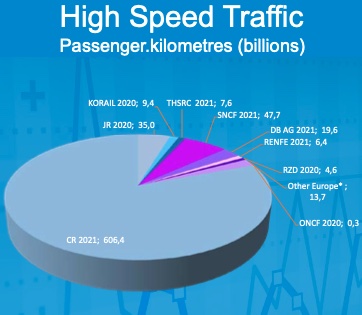

Here’s a pie-chart indicating the useage of China’s high-speed rail system compared with that of other countries. It’s taken from the 2022 edition of this annual report (PDF) produced by the Union International des Chemins de fer.

This chart shows that China Rail (CR) had more than 75% of the whole world’s passenger-kilometers of high-speed rail travel in 2021, at 606.4 billion p-km! Even with some possible disparities due to the pandemic, that is still astounding. France’s SNCF came in a very distant second with 47.7 billion.

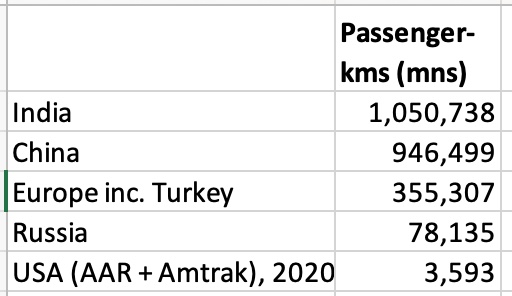

That same report has a plethora of other stats, too. I crunched some to come up with this little table about total p-kms traveled (not just the high-speed traveling) in various countries’ rail systems. The figures are for 2021 again, except the USA. (Which barely had any, compared with the other entrants there…)

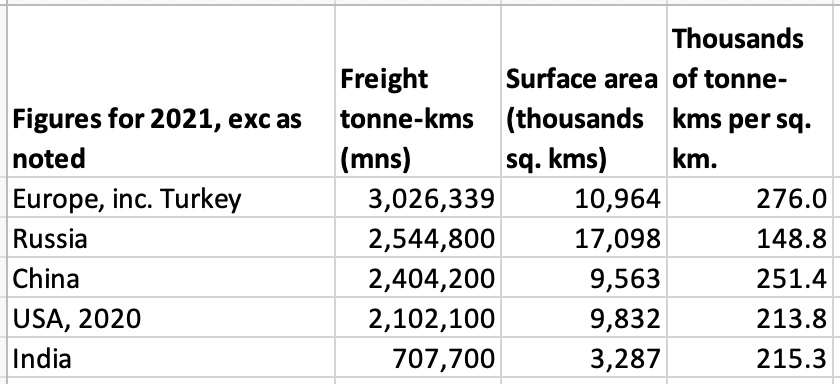

And here’s my table for the usage of rail for freight hauling in these areas:

From my work with the UIC numbers, I draw these conclusions:

- China has been doing very well in building its domestic rail networks across the board—for moving both freight and passengers, and especially for especially passengers on the high-speed lines.

- Russia, which has a massive surface area, has used rail pretty effectively for hauling freight, but apparently less well for hauling people. (Note, though, that its population is only 10% of China’s.)

- The USA is very far behind the rest of the developed world when it comes to passenger rail travel!

Parenthetically, as someone who has always loved rail travel, I have to admit that, now a denizen of Amtrak-land (ugh!), I am green with envy as I learn more about rail travel in China and the plans for its further development. Check out this very informative article on China’s high-speed rail system, from CNN last year. It says, inter alia, that:

No fewer than 37,900 kilometers (about 23,500 miles) of lines crisscross the country, linking all of its major mega-city clusters, and all have been completed since 2008.

Half of that total has been completed in the last five years alone, with a further 3,700 kilometers due to open in the coming months of 2021.

The network is expected to double in length again, to 70,000 kilometers, by 2035.

With maximum speeds of 350 kph (217 mph) on many lines, intercity travel has been transformed and the dominance of airlines has been broken on the busiest routes.

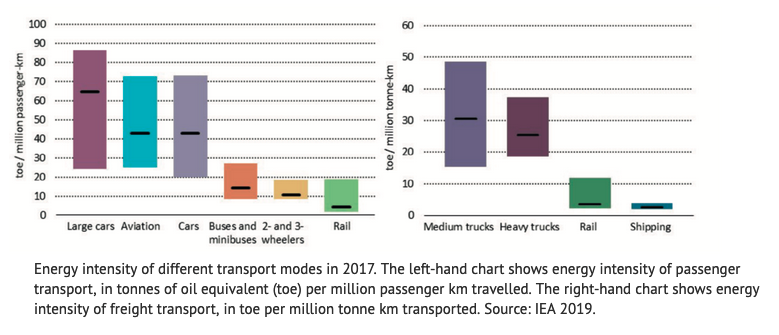

This last point is extremely important for the future of our planet. This 2019 report from the UK-based website Carbon Brief contains good stats on how much more carbon-efficient rail travel is than flying or traveling in large cars. Here’s one of their graphics:

Geopolitical implications

As I’d indicated above, the deeply West-European-dominated power structure that has governed the world for the past few centuries was established and then maintained by maritime adventurers from a handful of small polities perched on the western (Atlantic) coast of Europe. These were, to take them chronologically by the date of the establishment of their empires, the following:

- Portugal

- Spain

- England (later “Britain”)

- Netherlands

- France.

I have written at length elsewhere about the origins, early history, and world-changing significance of Portugal’s empire-building project, and also about how those other four empires developed in the 16th and 17th centuries CE. The lessons I drew from those studies included the following:

- When Portugal’s Vasco Da Gama rounded the southern tip of Africa in 1498 and entered the already bustling maritime trade routes of the Indian Ocean, he brought with him levels of sustained cruelty and violence that the peoples he found on and around this ocean had never seen before. And it was that capacity for violence (both physically, in terms of the types of weapons available, and psychologically, in terms of the readiness to use them) underlay Portugal’s ability to overpower many of the other polities they encountered—in India, the “Spice Islands” of East Asia, and elsewhere—and to lay the basis for the well-armed commercial empire they established in those places.

- The other four above-named polities then, over time, started competing with Portugal and each other to establish their (always well-armed!) trading stations on all the world’s continents. These deeply maritime empires all shared an ability to undertake, essentially, “hit and run” raids on the Indigenes they encountered which meant that even after enacting horrendous violence on these Indigenes, they did not have to stay thereafter and live alongside them as neighbors… Then, after they’d established super-extractive plantations in some of those distant areas these Europeans had the ability (and the ever-present firepower) to (a) work the local Indigenes to death on the plantations, if they chose, and then (b) replace those dead Indigenes as needed, with laborers they had captured from elsewhere in the empire and then transported across the ocean in conditions of chattel slavery.

- The birth and continuing development of these maritime empires itself helped in at least three of the cases—Portugal, Netherlands, England—to consolidate the emergence of a sense of “nationhood”, including in linguistic and other cultural forms, that otherwise would very likely not have existed or would have existed in a very different form.

It should not need to be noted here that in most cases, as convincingly demonstrated by Eric Williams and others, it was the hyper-profits made from those processes of imperial extraction that funded much of the “Industrial Revolution” in Europe.

The unfolding of Anglo colonial rule in North America was slightly different from the above template, in two ways:

- Here in Turtle Island, two centuries before Ian Smith tried to do the same thing in “Rhodesia”, the expansionist extremists among the local settlers declared and successfully defended their “Unilateral Declaration of Independence” from their metropole in London.

- For a century after 1776, the main focus of the United States’ colonial-expansion practice was directed toward territorial expansion, not maritime expansion.

But the U.S. Americans had brought with them from Europe a strong sense of cultural superiority over the Indigenes (whom they often saw as barely human), and the ability and willingness to use very lethal means to suppress them as they continued to steal their land and resources and to replace them with ever-new batches of settlers imported from Europe. Then, at the end of the 19th century, the final collapse of Spain’s trans-oceanic empire in the Caribbean and East Asia gave the Americans a good chance to continue building their own maritime empire, in addition to the territorial one they had now finished conquering.

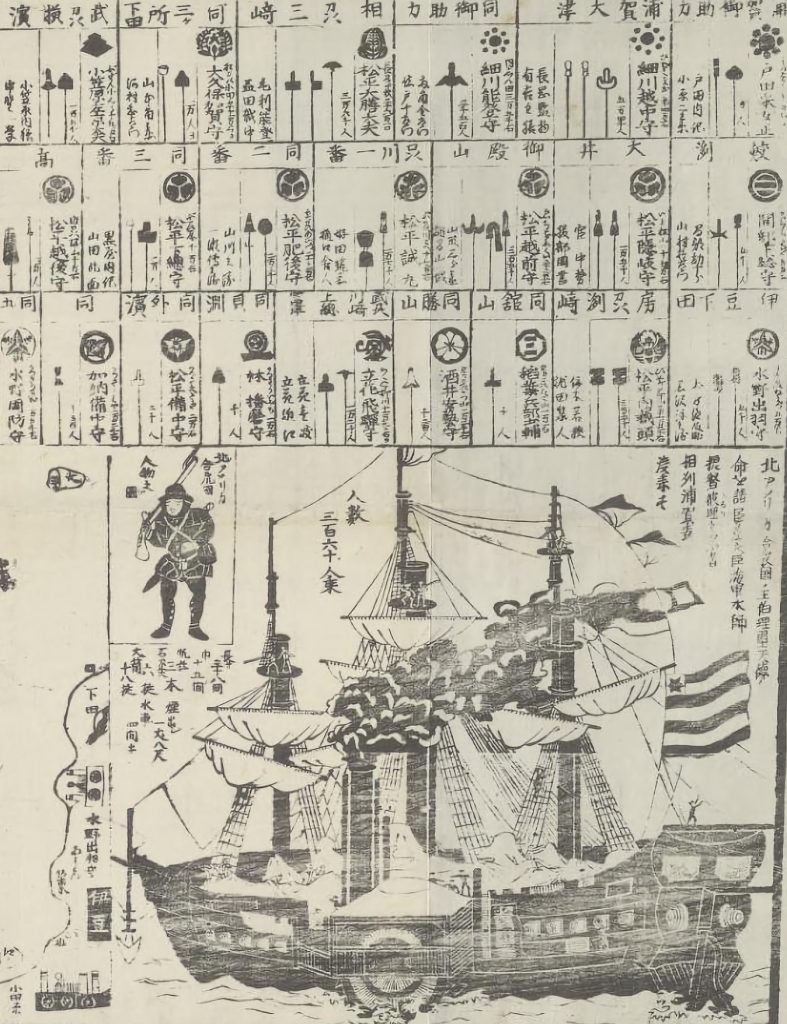

American missionaries, traders and naval vessels had anyway been plying the world’s oceans since the early 19th century. In Japan, in 1853-54, Commodore Matthew Perry used the eight ships under his command to force the shogun in Japan to “open” up the country’s ports to American traders.

And a decade before that, in July 1944, U.S. naval power had already forced the Treaty of Wanghia onto the Qing empire of China. This treaty allowed the United States to establish largely self-governing outposts in Shanghai and four other Chinese cities, in which:

- American companies could conduct business on the same favored terms that the British had earlier imposed on China in their just-concluded Treaty of Nanjing (which had guaranteed the British free access to China’s huge market for the opium that the British were very profitably cultivating in India), and

- Chinese subjects would be tried and punished under Chinese law and American citizens would be tried and punished under the authority of the American consul or other public functionaries authorized to that effect.

At that point, the U.S. government joined a whole string of West European governments—and Japan— in forcing upon China a series of “Concessions” that significantly eroded China’s sovereignty and freedom to determine its own destiny. Small wonder that most Chinese refer to the century that followed as “the century of humiliation.” (Soon thereafter, at the other end of Asia, several West European powers came together to force a parallel series of Concessions on the rulers of the still-large, land-based, Ottoman Empire.)

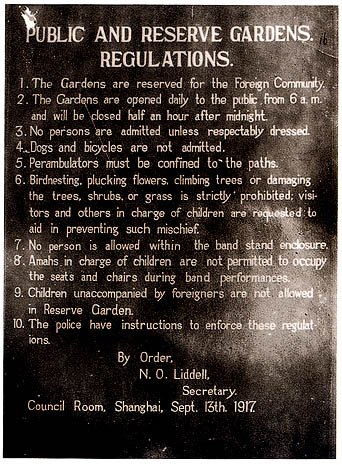

In Shanghai, to take one example of what ensued from the Chinese Concessions, in 1863 the British and American enclaves that had been allowed by the two treaties joined forces and created a largely self-governing enclave called the Shanghai International Settlement. (Unlike what happened in Hong Kong and Macau in that era, in the SIS the underlying sovereignty remained with China.)

By 1905 the SIS had a population of 501,000. By 1925 this number had grown to 1.14 million.

(In 1941, the Japanese military occupied the whole of Shanghai including the SIS. In 1943, as part of the attempt by the USA and Britain to muster Chinese support against Japan, both governments agreed to return governance of the SIS and many of the other 19th-century “Concessions” areas to China. In 1949, the Chinese People’s Liberation Army took over the whole of Shanghai during their victory over the Kuomintang.)

The shifting nature of global power

For nearly the whole of the past 600 years, the power to transform and then to govern the international order has grown out of the barrel of a long-distance gun. For the first 500 of those years, the most influential of those guns were naval cannons; and then, over the course of the 20th century CE, airpower came to also play a crucial role. Indeed, the United States’ use of air-delivered nuclear bombs against Hiroshima and Nagasaki could be seen as the apotheosis of the long-distance bombardments that had since the beginning been a key marker of “Western” empires.

But the introduction of nuclear weapons into the global power balance then increasingly, over the years that followed 1945 (and especially after the Soviet Union’s first nuclear weapons test in 1949), had the paradoxical effect of rendering not just their own use but also the use of increasing numbers and types of other long-distance/ standoff weapons increasingly unproductive and then, in political terms, actually counter-productive.

In the 1950s, the North Koreans and their Chinese volunteer allies, who had no nuclear weapons and who were subjected to horrendous bombardments by the United States (including, quite possibly, by biological weapons) managed to fight the very powerful U.S. intervention force in Korea to a standstill.

In October 1962, after the United States and the Soviet Union came to the brink of the actual use of nuclear weapons during the Cuban Missile Crisis, both sides backed down and agreed to a negotiated outcome.

In Vietnam, intense U.S. bombing and other military actions were unable to stave off the victory of the North Vietnamese and their allies.

In those same decades, intense military actions that Britain and France took against national-liberation forces in imperial holdings in places like Malaysia, Aden, Algeria, or Kenya were similarly unable to prevent those forces from achieving their goal.

The demise of Portugal’s longstanding empire in Africa was especially interesting. In 1974, discontent among the (mainly conscript) Portuguese forces fighting to suppress independence movements in Angola and Mozambique led those Portuguese units and their officers not just to give up the fight in Africa but also to go home to Lisbon and overthrow the whole reactionary government there.

The records of White South Africa and Israel—two European-origined settler-colonial outposts in the Global South—were also informative. In order to survive in the locations where they’d been planted, those outposts had to figure out a way to live alongside the various Indigenous groups who were their neighbors and which they could not, in the world as organized after 1945, simply wipe out through genocide.

White South Africans fought a tough series of battles against local liberation forces until 1991, then finally agreed to a negotiated stand-down (on terms very favorable to themselves.) As for the Israelis, they demonstrated their considerable military might by using it against their neighbors repeatedly from 1947 and—in the case of Syria and Gaza—periodically until today. Throughout those decades, Israel’s use of military force successfully forced Egypt and Jordan to sue for peace. But despite all the suffering Israeli violence has imposed on Palestinians since 1947, this violence has never succeeded in forcing Palestinians to give up their claims for full rights, including the rights to return and to self-determination.

Israel’s use of force against Syria and Lebanon has proven similarly un- or counter-productive. The large-scale military assault that Israel launched against Lebanon in 1982 did succeed in forcing the Palestinian guerrilla units to leave Lebanon. But Israel’s subsequent attempt to force a peace agreement on Lebanon itself proved short-lived; and meantime the continuing presence of Israeli occupation forces in South Lebanon “succeeded” merely in incubating the new, militantly anti-Israeli Lebanese fighting force, Hizbullah. In 2006, an attempt by Israel to repeat its 1982 assault on Lebanon ended up a humiliating fiasco; and Hizbullah has remained deeply embedded in Lebanese society and politics ever since.

And then, in the current century, there have been Washington’s massively sized—and budgeted—invasions of both Afghanistan and Iraq. We know how disastrous these two campaigns have been, at the humanitarian level, for the two countries’ peoples (and their neighbors.) But politically, what did they achieve for the United States? We must surely conclude that the net political effect of each of them turned out to be extremely negative.

In Afghanistan this is indubitable. The Taliban are back. The scenes of American allies fleeing for the exits in August 2021 left lasting marks worldwide. In Iraq, too, the net political effects for Washington have been very negative. The United States’ lengthy occupation of Iraq fractured the whole country; incubated the Islamic State (IS); and sent waves of instability into Syria.

Meantime, the geopolitical impact of these two U.S. military campaigns and the many other military or economic-punishment campaigns that Washington has waged in this century throughout the Global South—in Libya, Syria, Somalia, Venezuela, Mali, and elsewhere—has completely undercut the credibility of any claims the United States can make to being a power that “leads” or even just upholds the world political order.

China’s longstanding campaign to grow its global political power has, by contrast, been built on very different foundations: primarily those of steadily strengthening economic ties with countries around the world while providing a strong example of how countries in the Global South can lift their people out of poverty and backwardness through sustained investment in infrastructure and economic development.

In the post-1945 world, it turns out, global political power no longer grows out of the mouth of a naval cannon or a “strategic” bomber, but rather from the thousands of kilometres of railroad track, the bridges and tunnels that carry their sleek passenger and freight trains, the towering cranes at fully automated ports, and the mouths of pipelines…

This is a wondrously welcome turn of events! Which is not to say that wars are no longer being fought (as we well know), or that force and violence have completely lost their role in world affairs. But if the past decades have shown us anything, it is that campaigns to use massive military force at long distances from home are deeply counter-productive and that in most parts of today’s global arena economic power and other forms of “soft” power have started to outperform the traditional tools of the military.

The Ukraine-Russia paradox

Of course, I need to say something here about the ongoing conflict in Ukraine: a place where hard military power has clearly retained considerable importance.

My first observation here is that the focus that the United States and its allies have placed for the past 20-25 years on long-distance/ standoff weaponry in its campaigns in Afghanistan, Iraq, and elsewhere has left many of these Western countries very short of the basic materiél needed to wage large-scale ground warfare. And the steep decline that the broad manufacturing base in the United States and other NATO countries have seen over those same years makes it very hard just to speedily crank up military production lines in the way that was done in the 1940s or even the 1970s.

As JCS Chair Mark Milley and others have warned, there is a very real chance that within the coming weeks or months Ukraine’s NATO backers will run out of the kinds of weaponry and ammo that the UAF’s ground forces will needs if they are to hold their, er, ground.

Another observation is that (as I’ve noted earlier) Washington’s attempt to force Russia to its knees through the imposition of uber-punitive sanctions has not succeeded. Indeed, to the extent that its spurred many of the other members of “Team Sanctioned” and “Team Tarriffed” from around the world to collaborate on devising ways to reduce or end their exposure to such actions from Washington, the U.S. sanctions on Moscow can be described as having been quite counter-productive.

In the Ukraine conflict, military force has not been shown to be un- or counter-productive. Far from it. But it is a certain kind of military force that is being used there: namely, large-scale ground forces on a scale not seen since WWII. And such forces, in those two countries as anywhere else, require a very robust manufacturing base to sustain them.

The return of China, land empires, and the Global South

On the surface of things, the three decades since the end of the U.S.-Soviet Cold War seemed for a long time to be a period in which the United States exercised unchallenged hegemony over the international order. But underneath Washington’s often arrogant flaunting of that power, changes of deep global significance were brewing.

Those changes were at the level of both hard and soft power. Here’s a quick initial list:

- The kinds of stand-off weapons that the U.S. military gloried in developing and using were proving to have ever-lessening utility in effecting the stated real-world political goals.

- The arrogance with which Washington wielded those weapons, while bending many of the instruments of global governance to its will, provoked ever-growing resentment in the Global South. (The decision to invade Iraq in 2003 was a key turning point in this regard.)

- The hypocrisy with which Washington paraded itself as a supporter of “rights” while giving strong continuing support to Israel and other evident rights-abusers cost it dearly in terms of global soft power.

- The cruelty of the economic sanctions Washington maintained on countries like Iran, Cuba, Syria, and Venezuela further alienated millions of people throughout the Global South.

- The vigor with which U.S.-dominated financial institutions like the World Bank and IMF worked to impose neoliberal policies on countries in the Global South imposed real hardships, especially when contrasted with the investments China was making in infrastructure development in many of these same countries.

- The selfishness with which Western countries guarded the patents to Covid vaccines, denying to pharma manufacturers around the world the ability to co-produce them…

That list of U.S. mis-steps and misapprehensions could go on and on. It’s worth reiterating here that the peoples of the Global South constitute a very strong majority of the whole of humanity, with the “White” countries of the “West” forming only around 12% of the whole. Also worth noting: that most of the factors in any such list as that above are factors of soft, not hard, power.

The net result of all these processes has been the significant re-emergence onto the world scene of a China that is self-confident, smart, and strongly connected to other power centers across the Global South through ever-deepening economic ties and through a series of interlocking institutions like BRICS, the G20, the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, and the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank.

In world-historical terms this is huge. It means that the 600-year era in which world affairs was dominated by self-righteous adventurers from a handful of small West-European countries, and their spawn, is now—finally—coming to an end. Phew.

One thought on “China’s rise and the changing nature of global power”

Comments are closed.