The image above shows a Liebherr mining excavator and associated truck. Such an excavator can weigh > 800 tons and produce 4,000 horsepower

The crisis that our climate is in is now evident to all. It reminds us of the extreme risks humankind ran by failing to rein in our emissions of CO2 and other greenhouse gases. Many of us have long understood that fossil fuels that exist in limited quantities—and that as humankind draws those fuels down toward “empty” we will need to have in place robust energy systems based on renewables. But there are three other broad types of planetary resources whose depletion by humans is now also close to crisis point. These three categories are: metals, non-metallic minerals, and biomass.

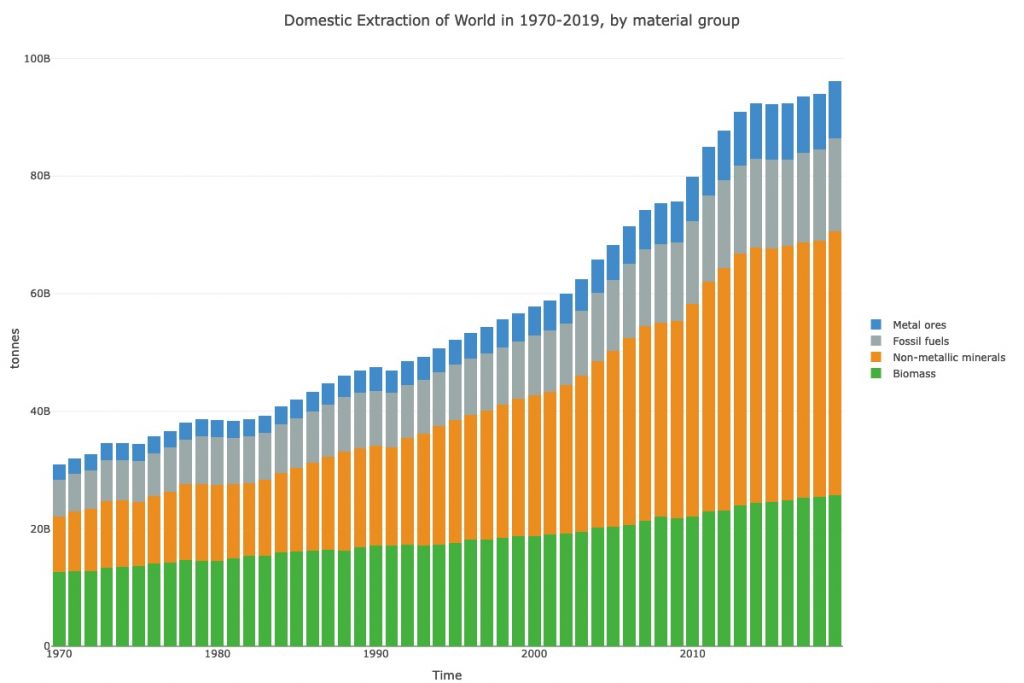

This graph from the University of Vienna’s excellent Materialflows.net website tracks the annual global extraction of all of these four resource categories over the half-century 1970-2019, measured in billions of tonnes. In those years, the annual extraction of fossil fuels (grey) increased by around 150%. But the annual extraction of of metals (blue) and non-metallic minerals (orange) both increased by around 350%.

The world population of humans increased by 110% in that period—which was roughly proportional to the increase in the extraction of biomass, shown there in green.

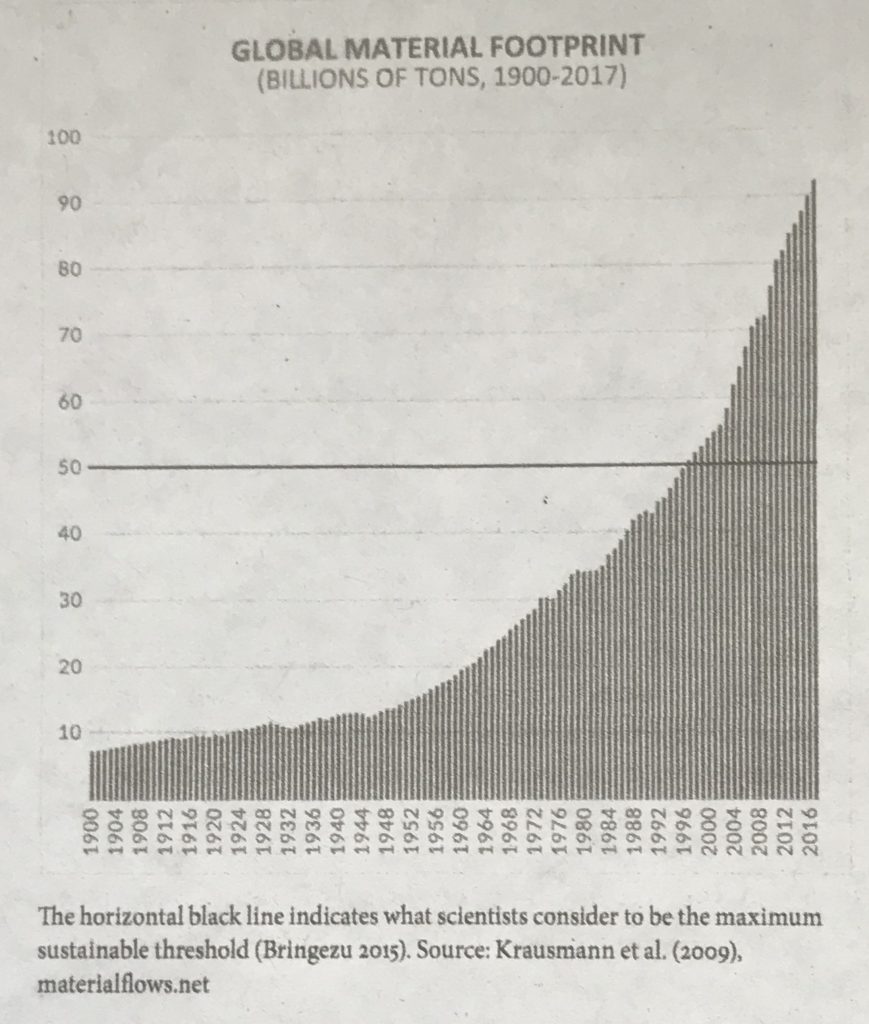

By the way, sustainability scientists calculated a while back that 50 billion tonnes of total annual resource extraction is roughly what’s sustainable over the long haul. We breached that limit in the mid-1990s and are now close to extracting twice that amount.

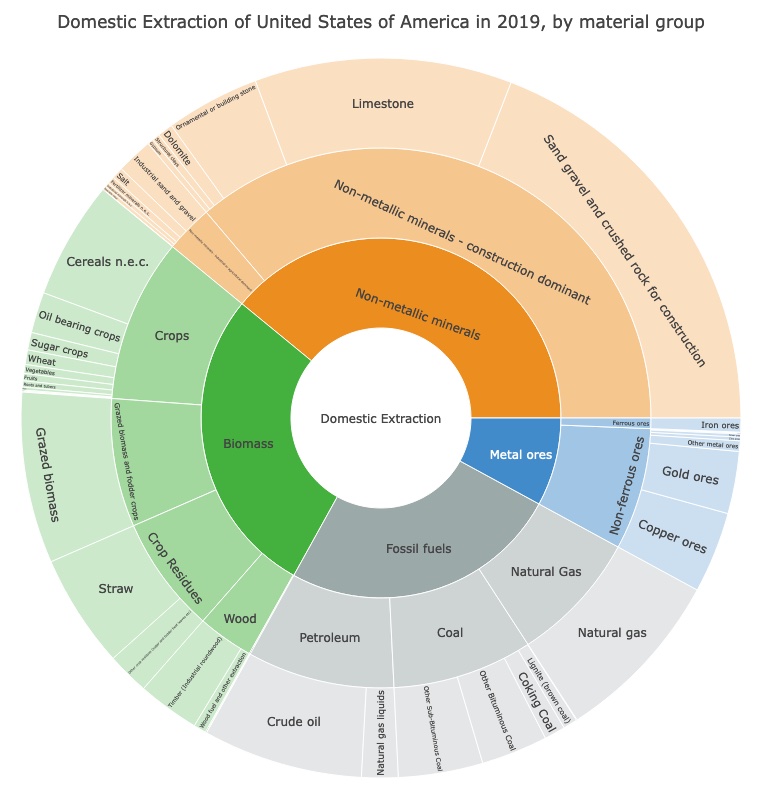

What do these resource categories contain? If you click on the “sunburst” chart here, which shows the domestic extraction activities of the USA in 2019, then each successive ring going out from the center gives more detail of what makes up the category. For the important (orange) “Non-metallic minerals” category, the vast majority of the tonnage extracted was for purposes of construction—limestone, sand, gravel, etc.

But our planet has only so much “stuff” to offer us; and as we use up more and more of it, extracting what remains becomes ever harder, and requires ever more energy to do so.

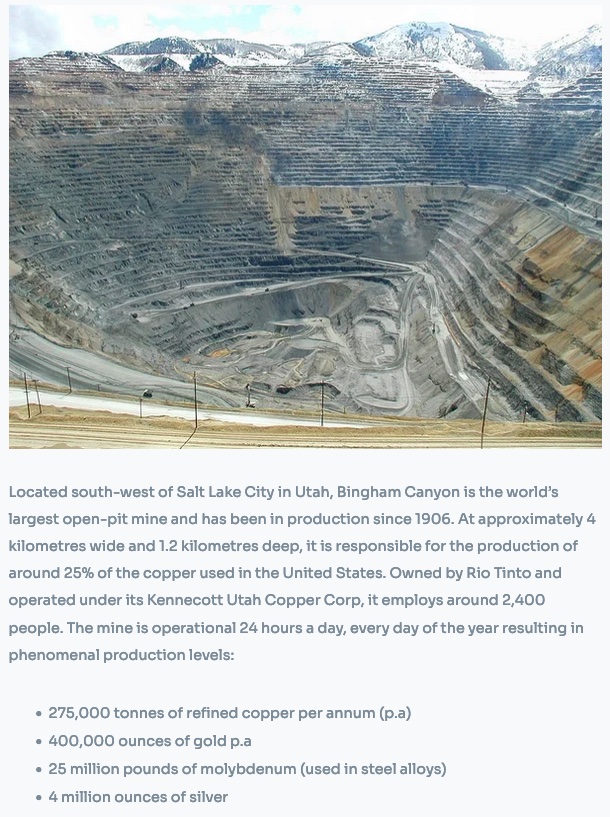

This is just one of the ways in which the finitude of physical resources interacts in what looks like an escalating death loop with the challenges of greenhouse-gas emissions and the climate crisis. Just look at the size of some of the diggers used in today’s open-pit mining operations (as shown in the banner image above)! Then estimate how far some of those massive trucks—which appear like tiny pin-pricks on the photo of the massive open-pit mine shown here—have to travel, heavily loaded, to bring the gouged-out minerals up to the surface. (Click to enlarge that image.)

Extractive activities on such a scale cannot, of course, go on forever. Indeed, they may not go on for very much longer, at all…

A matter of global justice

The resource crunch that humankind is fast approaching is absolutely a matter of global justice. It seems it is generally far better understood in Europe (which has long been a net importer of many types of raw materials) than it is here in the United States. But for more than a century now, Western Europe and the Western-heritage settler states of the United States, Canada, and Australia have all been responsible for a damagingly disproportionate amount of resource extraction worldwide. And the “Material Footprints” of these nations—a measure that includes the resources that they extract domestically, the resources they import from elsewhere, and the resource-base of the finished goods they import from elsewhere and consume—is also disproportionately high.

In his excellent book Less Is More: How Degrowth will Save the World, justice activist Jason Hickel goes back earlier than the data presented on the Materialflows.net website to show how the “global material footprint” of all of humankind increased from 1900 through 2016. (As shown.)

The horizontal line there is at the level of 50 billion tonnes/year that is what sustainability scientists judge to be “sustainable.”

It’s key to note that that whole period since 1900 has been one in which nations of West-European heritage have held great sway over the governance of the world. Until the 1950s and 1960s, corporations from a number of European nations rapaciously and directly looted resources from much of the Global South; and since then, corporations from those countries, the United States, and other “White” countries have enjoyed a standard of consumption far greater than that accessible to most citizens of the Global South.

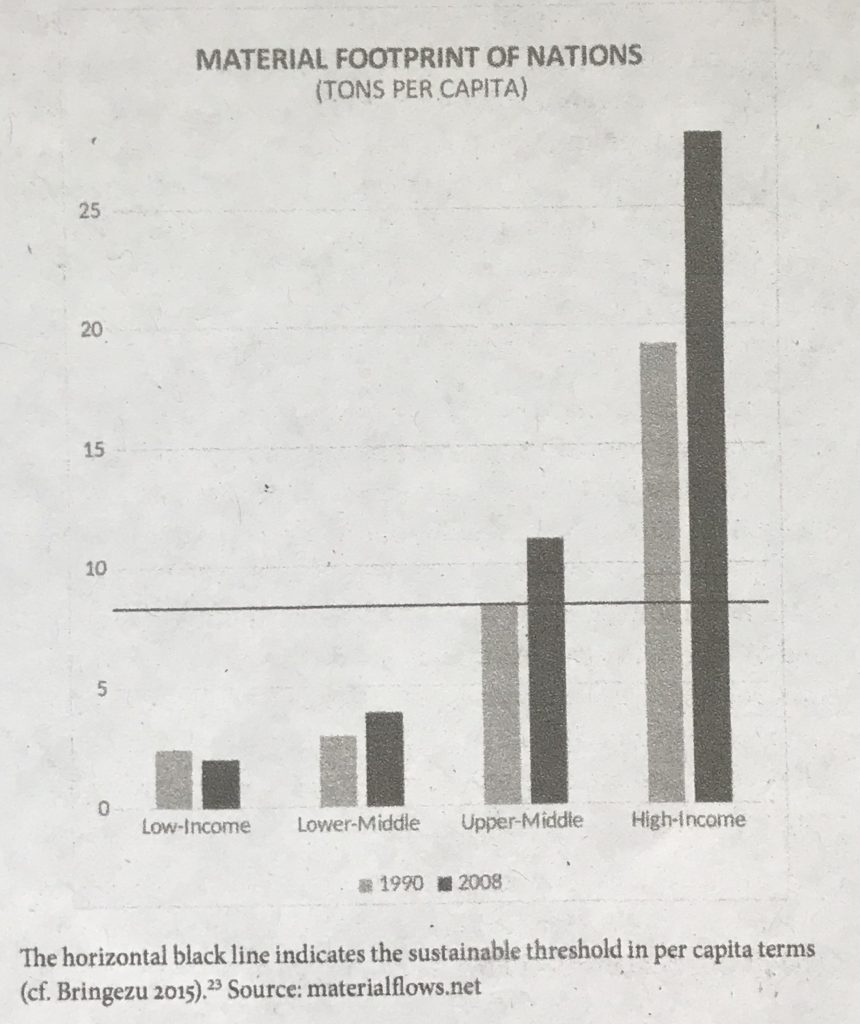

Hickel used data he has taken from Materialflows.net to compile the bar-graph shown here that shows the per-capita material footprint of nations according to their general income levels, in both 1990 and 2008. One first observation is that of these income-groups, the per-capita material footprint of people from low-income countries declined over those 29 years, while that of people from high-income countries went up considerably.

Another kind of ‘decoupling’

Back in Adam Smith’s day, economics was still a branch of “moral philosophy”, that is, ethics. And the Greek origins of the word economics, oikos+nomos, refer to the kinds of rules (nomos) that ought to order the running of a good home (oikos). The word ecology, comes from oikos+logos, referring to a more scientific and seemingly less directive study (logos) of the earth that is our planetary home. (For what it’s worth, in many Eastern churches, there is a powerful concept of “oikumene”, which literally means a “homecoming”.)

Well, I guess Adam Smith has been dead a long while now. Today, nearly the whole of “economics” as it is taught, discussed, and generally understood around the world pays little heed to ethics and is focused on a fetishized regard for Gross Domestic Product (GDP), in particular on the need for continued growth of GDP.

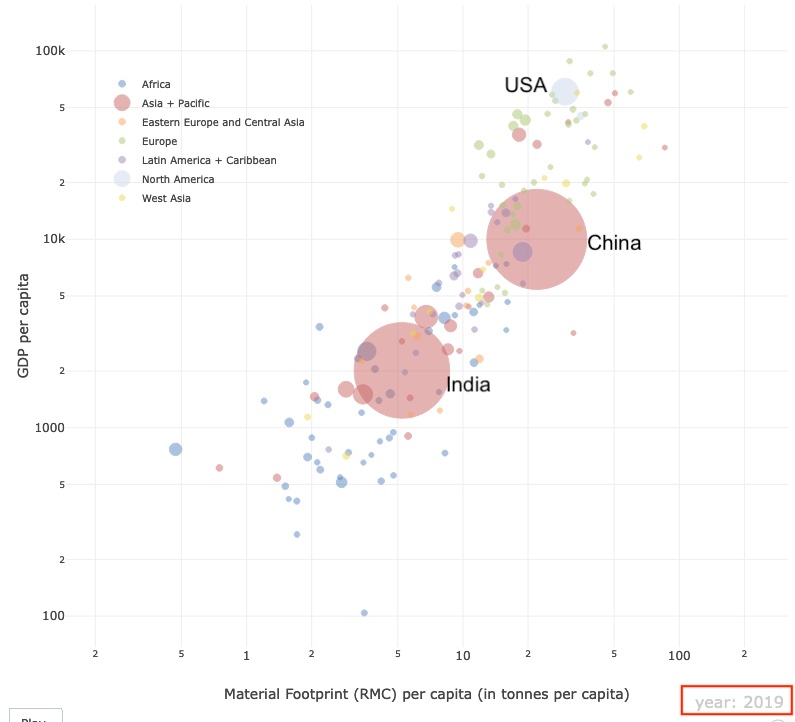

Generating an increased GDP nearly always requires increasing a country’s level of consumption of resources, as can be seen from a number of the different visualizations provided by Materialflows.net, such as this one, which places countries on a chart according to their per-capita GDP (y-axis) relative to their per-capita Material Footprint (x-axis.) Both axes are logarithmically scaled.

Two important comments here:

- It is quite possible—indeed, necessary at this point in time—for all of us lucky enough to have incomes high above the global mean to wean ourselves away from the intense valorization of GDP as a measure of human wellbeing and also from the longstanding fetishization of GDP “growth”.

- It is also quite possible and necessary to decouple the quest for the “GDP” that people need from a proportional increase in resource consumption. This, indeed, is the kind of “decoupling” sought by people in the field of sustainability studies. (It is quite distinct from the vicious and blindly nationalistic “decoupling” that many U.S. politicians have been urging, of the U.S. economy from China’s economy.)

How can such decoupling be achieved?

As mentioned above, scientists and politicians in some European countries are far ahead of most of their American colleagues in investigating these issues. For example, the excellent Materialflows website is a joint project of both Austria’s Federal Ministry for Climate Action, Environment, Energy, Mobility, Innovation and Technology and the Vienna University of Economics and Business. And specialists from East and Central Europe also play leadership roles in the U.N. Environment Program’s International Resource Panel (IRP).

Both these bodies offer a wealth of online resources on the different aspects of the resource-crunch challenge. For example, the IRP has a good basic Glossary of Terms, and a portal to several instructional videos, including this one (4:41) that introduces the basic concepts and methods involved in Decoupling.

For its part, Materialflows offers, in addition to its many terrific data visualizations, numerous pages of helpful and informative text, such as this one on Decoupling.

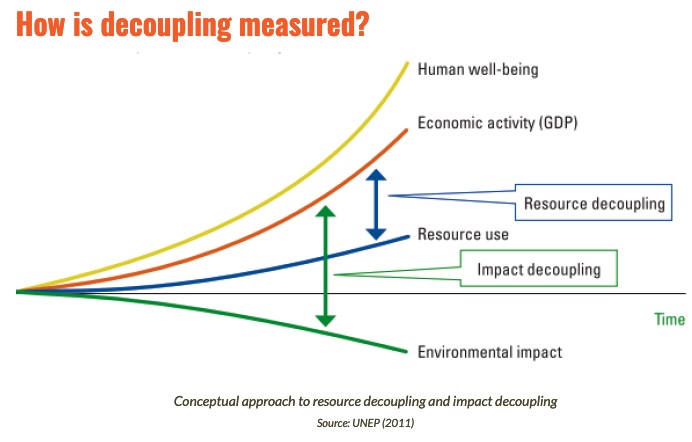

One basic distinction here is between Resource decoupling—getting more economic usefulness from any given amount of raw materials used—and Impact decoupling, which looks at the impact on the environment of any economic activity in terms of both resource depletion and generation of greenhouse gas emissions and other harmful wastes.

How to live more mindfully

I want to give a shout-out to the amazing Sri Lankan writer and thinker Indi Samarajiva, many of whose writings have (along with Jason Hickel’s Less Is More) forced me to think through these issues more deeply. Indi has a thorough, and duly wry, understanding of U.S. culture and its values, having grown up in an immigrant family in Ohio. He also has deep affection and understanding of the Sri Lankan society to which he has largely returned.

And he’s a truly terrific wielder of the English language! If you’re able to follow his work on Medium, you certainly should. Just since the beginning of July he has published How Colonizers Changed Words and Kept Colonizing, How War is Peak Capitalism, The Body Horror of the Highway, What is GDP, and more than a dozen other super-thoughtful essays.

In this essay, Why Renewables Won’t End Environmental Destruction, he writes:

Colonialism began with renewable energy. Wind to sail across the world, solar to grow cash crops, and human blood, sweat, and tears to grow them. For the violent and resource-poor tribes of Europe, ‘blood for oil’ began as ‘blood for sun’. Vile companies like the VoC [the Dutch East India Company] (the first multinational) technically had zero emissions. By this logic, you could say that early colonialism was ‘sustainable’ but it obviously wasn’t. Because the problem isn’t the energy source, it’s what you use that energy for...

One of the important sources Indi uses in his writings on economics and the resource crunch is an open-source, 2021 textbook Energy and Human Ambitions on a Finite Planet, by U.C. San Diego physics prof Tom Murphy, Jr. You can download the entire 465 PDF of Murphy’s book here.

Energy and Human Ambitions (EHA) was written as a fairly general, though slightly math-heavy, introduction for college students to the whole question of planetary resource limits. Much of it merits close reading, but I found two portions near the end particularly rewarding.

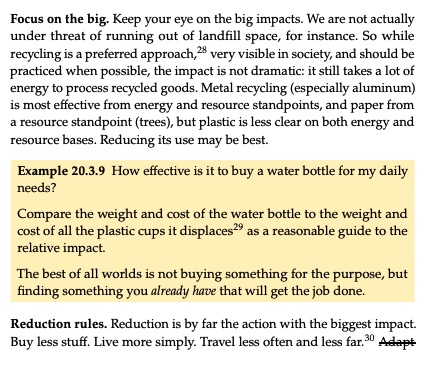

In one of these, pp.353-63 (download PDF of these pages here), Murphy explores actions that his readers—U.S. college students, and others—can take to reduce their own carbon footprints. Along the way, he introduces lots of examples of specific decisions a person might make as well as the thought processes behind some of the decisions he has made in his own life. Here is an excerpt from this section:

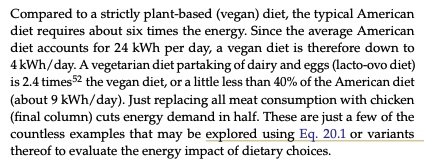

He has suggestions for many kinds of choice an individual might make, including dietary choices. Here, after doing some math-heavy explorations, he concludes with this:

Though he warns elsewhere against virtue-bragging, Murphy also writes (p.343) that through making mindful choices he has been able to reduce his own average daily energy usage to 26 kWh, from a U.S. average of 93 kWh. Pretty inspiring!

Not just individual choices

In his book, Murphy alludes fairly briefly to the fact that, however many thoughtful choices individuals in a society like the United States might make, by far the most significant decisions regarding humankind’s total resource use are those made by governments. In his Chap. 19, “A Plan Might be Welcome”, he notes that until now, humankind hasn’t needed to have a “global master-plan” for resource use, but now it is becoming increasingly clear that one is needed. He notes that the United Nations is the closest thing we have to a global government, but that it lacks enforcement powers.

He then writes, p.321,

[H]ow might a viable plan emerge? Who might produce one? Corporations cannot be expected to lay out a responsible plan for our future. Their interest is in company health and profits…

Governments are in a better position, presumably interested in the long-term health and viability of the country. Many governments, however, are constrained by election cycles that in the U.S. are every 2, 4, or 6 years. Decades-long planning is not natural in such high-turnover systems. Authoritarian governments may be in a better position to effect long-term planning, and even have the ability to impose sacrifice for longer-term goals. Yet, here again the goals are not aimed at achieving global peace and prosperity, but rather securing that particular country’s fortunes and survival…

I disagree with his implication there that governments that are capable of doing longterm planning are all “authoritarian.” But it nonetheless seems evident that one of the governments that is currently doing the most to make concrete, multi-decade preparations for the coming era of resource shortage is that of China.

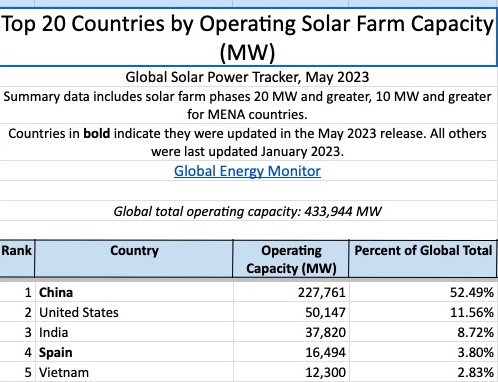

In this essay, which I published last month, I presented several pieces of recent data from the California-based non-profit Global Energy Monitor GEM), that convincingly show that China has already established itself as a leader in the transition to renewables. It has already installed 52.49% of the world’s total (large-scale) solar-farm capacity, and 39.46% of the world’s wind-farm capacity…

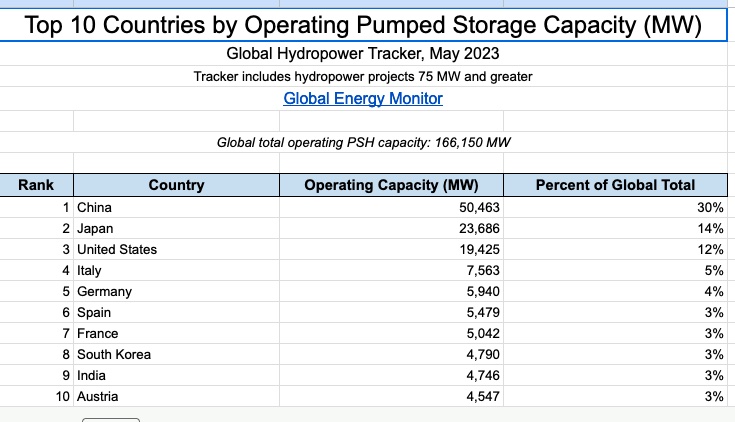

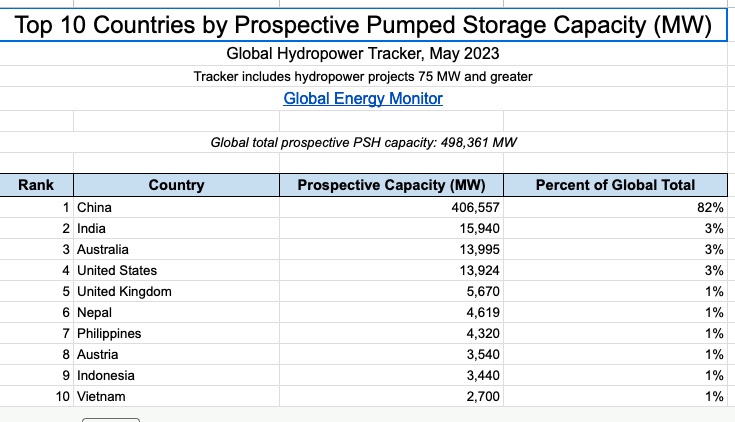

In those domains, as in the also-important domain of pumped-storage hydro—which has emerged as a key way to even out electric supply and demand, especially in the context of a reliance on renewables—China is not just the current leader but is actively pursuing plans to increase its global lead in what GEM terms a “Race to the Top”. Check out these numbers from GEM:

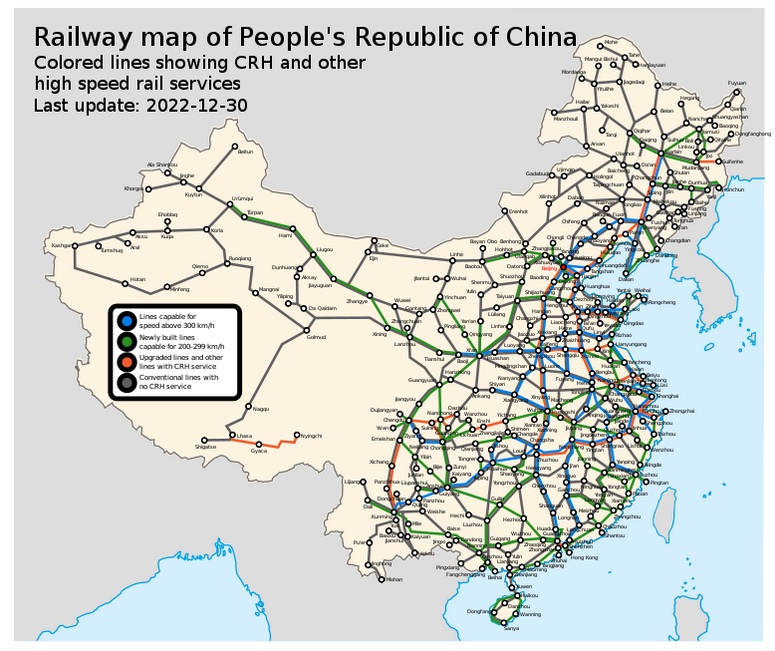

Meanwhile, in another key energy-related domain, that of inter-city transport, China has also emerged as a clear global leader—something that I wrote about here.

Now of course all of China’s investment in infrastructure projects has taken, and will continue for some years to take, a considerable investment of physical resources. That is almost certainly why, though Pres. Xi Jinping has on a number of occasions publicly committed his government to the elimination of all CO2 emissions by 2060, he also notes that China’s emissions will continue increasing for a few more years before they peak “before 2030.” (This puts China a little at odds with the timeline established by the 2015 Paris Agreement, which seeks concrete reductions before 2030.)

This phenomenon by which a country that seriously commits to reducing or eliminating its reliance on fossil fuels (and on other finite physical resources) will probably need to “invest” in using more such resources for a short while, in order to build the needed, more sustainable infrastructure is one that Tom Murphy referred to explicitly in his book. On his pp.310-11 (download the PDF of those two pages here), he introduced the concept of the Energy Trap.

He writes there:

Imagine now that we find ourselves having reduced access to oil, driving prices up and making peoples’ lives harder. Now the government announces a 16 year plan to divert 25% of energy into making a new infrastructure in an effort to reduce dependence on fossil fuels. That is a huge additional sacrifice on an already short-supply commodity. Voters are likely to respond by tossing out the responsible politicians, installing others who promise to kill the program and restore relief on a short timescale. Election cycles are short compared to the amount of time needed to dedicate to this sort of major initiative, making meaningful infrastructure development a difficult prospect in a democracy…

Now it is perhaps more apparent why this is called an energy trap: short-term political and economic interests forestall a proactive major investment in new energy, and by the time energy shortages make the crisis apparent, the necessary energy is even harder to attain. Short-term focus is what makes it a trap.

One wonders how democracies will fare in the face of declining resources. The combination of capitalism and democracy have been ideal during the growth phase of our world: efficiently optimizing allocation of resources according to popular demand. But how do either work in a decline scenario, when the future is not “bigger” than today, and may involve sacrifice? We simply do not yet know.

I strongly contest the assertion he makes there that “The combination of capitalism and democracy have been ideal during the growth phase of our world… ” Ideal for whom? Certainly not ideal for all those peoples of the Global South from whose suffering were born—in a rapaciously colonialist Western Europe— the “Industrial revolution” and its step-brother the purely profit-seeking system of corporate capitalism! And not ideal, either, for the millions of European small farmers forced off their held-in-common lands by “enclosures” to make way for the privatization and monetization of those lands and to force those low-income Europeans into drudgery in the early capiatlist factories.

But still, the larger point Murphy makes about the difficulty, within a polity focused on short-term electoral goals, of formulating and pursuing an investment plan aiming at long-term ecological sustainability is certainly one worth grappling with.

I just return, at this point, to the relatively much smarter and more engaged policies discussed and adopted by a number of European societies that have strong democratic traditions and commitments. The short-term-ism that Murphy decries is not a necessary feature of all “democratic” societies. It is one that is, I think, particularly acute within a U.S. polity in which money from corporate donors carries particularly heavy sway and in which the education levels of many of the voters are considerably lower than in most European countries.

Still, all is not lost, even here in the United States. Though our democratic system is currently badly impaired (as I wrote last week), the extreme weather events that many parts of the country have experienced this summer should act as a wake-up call. And we do, now, have an increasing number of educational resources that can help us think through some of the policy steps—as well as the personal steps—that we need to start taking if we want to save Planet Earth for all of our grandchildren.

The idea to use the coercive power of government for the greater good is a poisoned chalice, it must be resisted bu all those who set out to “save the word”, the seductive appeal of being able to control our destiny is hard to resist by starry eye intellectuals. there are no solutions only compromises and those who ll bear the cost should decide for themselves, not some unaccountable beurecrat, who the rules and resultant deprivation won’t apply to. you presuppose that your messianic plan to save the world is right and you know all the possible unintended consequences of your actions. Good intentions do not justify using coercion/force( which is basically the only way you can attempt to alter human behaviour on the scale you propose ala the great tragic communist experiments of the 20th century),it always leads to more human suffering than it was planned to avert.