When Pres. Biden announced he was sending first of all one aircraft carrier battle group, then a second one, then also a Marines expeditionary unit to West Asia (the Middle East), each time the rationale he gave was that this was to “deter” actions by hostile actors. These declarations were completely in line with the main rationale provided since the 1940s for the maintenance of a huge U.S. military presence all around the globe. And they’ve been more or less accepted at face value by a U.S. commentatoriat that generally sees no problem in these large displays of force and that in recent years has been thought to be strongly averse to the employment of any U.S. troops in actual warfighting.

So if the president claims that the deployment of large U.S. “deterrent” forces to war-zones will help to prevent the escalation of violence, what could possibly go wrong?

Actually, a lot—and all the more so, since these displays of U.S. force are not accompanied by any U.S. diplomatic moves that aim clearly for a ceasefire in the hostilities that have continued between Israel and Hamas in Gaza for 13 days now. In this context of the absence of de-escalatory U.S. diplomacy in West Asia, the deployments of large carrier battle groups and the Marines unit(s) have thus far served mainly to escalate regional tensions.

Let’s quickly back up a bit and look at (a) how deterrence is supposed to work and (b) how the catastrophic failure of the “deterrence” that Israeli leaders thought they were projecting towards Hamas in Gaza actually led to the current crisis.

How deterrence works (or is supposed to)

If Party A is projecting deterrence against Party B, then it means that the leaders of Party A think its military is capable of inflicting politically (or even existentially) significant harm on Party B; and the leaders of Party A communicate clearly to Party B that “If you take Action X, then you can be certain that we will take Action Y, which will inflict unacceptable harm on you.”

Throughout most of the U.S.-Soviet Cold War, deterrence theory formed the core of the strategic relationship between these two nuclear-armed power centers, and it developed many sub-wrinkles such as the need for each party to be able to develop—and to demonstrate that it had developed—survivable “second-strike” capabilities, meaning that it could more or less “absorb” even a punishing surprise first strike on its nuclear forces and retain a capability to launch a “second-echelon” nuclear strike in return. What resulted was described as a situation of “Mutually Assured Destruction”, acronym MAD. Thank God that the leaders of the two countries were able to reach out to each other in the late 1980s and help each other climb down from that terrifying decision tree. (Though of course, later leaders in Washington then let the relationship with the Soviet successor state, Russia, wither very badly in the decades that followed, which has led to the current dangerous stand-off over Ukraine.)

In the region of West Asia, Israel is the only nuclear-armed state and has highly developed missile forces, an air force, and a submarine force all capable of delivering nuclear or non-nuclear weapons over a very broad distance. But its leaders generally do not publicize these capabilities, and their use of extreme strategic hypocrisy in this regard is generally supported and perpetuated by Western political elites who talk endlessly, for example, about the “threat” that Iran, or earlier Iraq, Syria, or even Egypt, might develop nuclear weapons… while keeping completely and mendaciously mum about Israel’s known possession of an advanced nuclear-weapons capability. But the fact remains that the “deterrence” that Israel projects towards its neighbors on a daily basis is nearly always of the non-nuclear kind…

Israel and deterrence

Israel has numerous non-nuclear military capabilities that that can be, and have been, widely demonstrated and used as a “deterrent” against other powers in West Asia. In the aftermath of the 1967 war, when it was able to defeat Arab armies on three fronts, seizing significant chunks of land from each of them—and all that within just six days of fighting—its ability to deter any pushback was particularly high. In 1973, the leaders of Egypt and Syria showed they were not deterred from trying to use force to regain their own lands that had been occupied in 1967, but both leaders and their armies communicated clearly that they did not intend to use force against Israel itself.

In 1982, Israel launched a huge ground invasion of Lebanon and was able (after roughly six weeks fighting) to realize its aim of expelling from the southern half of the country the PLO forces that had previously been well dug in there. However, in the end it realized that goal only through negotiating their exit. And thereafter, Israeli forces stayed in Lebanon for 18 years. They were unable to translate that presence into winning PM Sharon’s other political goal of forcing the Lebanese government to sign a peace agreement with Israel. And indeed, those 18 years of Israel’s occupation of South Lebanon ended up incubating the emergence of the most powerful anti-Israeli fighting-force ever seen in the Arab world: that of Hizbullah, which was homegrown and deeply rooted in Lebanon’s ancient Shiite community, though it also received some support from Iran and Syria.

In 2000, under intense continuing pressure from Hizbullah, the Israeli military retreated completely and fairly humiliatingly from Lebanon. Six years later, an incident in which Hizbullah kidnapped a couple of Israeli soldiers at the border sparked what Israeli PM Ehud Olmert had planned to be a very harsh, colonial-style punitive raid against not just the Hizbullah military but also the Hizbullah stronghold in the Southern Beirut “Dahiyeh” (neighborhood), and against many crucial points of Lebanon’s national infrastructure, as well. This 2006 Israel-Lebanon War inflicted terrible casualties on Lebanese people and their national infrastructure. That Wikipedia page tells us it, “is believed to have killed between 1,191 and 1,300 Lebanese people, and 165 Israelis. It severely damaged Lebanese civil infrastructure, and displaced approximately one million Lebanese and 300,000–500,000 Israelis.”

In October 2008, the commander of Israel’s Northern Front, General Gadi Eizenkot, explained that what the IDF had attempted in Lebanon in 2006 was something that soon became known as the “Dahiyeh Doctrine.” Eizenkot said that what happened in the Beirut Dahiyeh in 2006 would,

happen in every village from which shots were fired in the direction of Israel. We will wield disproportionate power against [them] and cause immense damage and destruction. From our perspective, these are military bases. […] This isn’t a suggestion. It’s a plan that has already been authorized. […] Harming the population is the only means of restraining [Hizbullah head Hassan] Nasrullah.

Just two months later, in December 2008, when the IDF moved against Hamas in Gaza, it seemed to be pursuing something exactly like the disproportionate (= highly escalatory) response of a “Dahiyeh Doctrine”… and again, when it moved against Hamas in Gaza in 2014 and 2021. And certainly, when it moved against Hamas in Gaza 13 days ago.

However, it is also necessary to recall that in the Israel-Lebanon war of 2006, Israel’s actual pursuit of the original “Dahiyeh” assault proved absolutely catastrophic and humiliating for the Israeli military and their political leaders. After 33 days of relentless attacks against Lebanon from ground, sea, and air, the IDF was unable to suppress the Hizbullah units’ fire (which included long-distance rockets sent deep into northern Israel), and Israel had to beg for a ceasefire. The IDF ground troops who had advanced deep into Lebanon had to retreat in a very humiliating fashion. And since then, there has been an effective state of mutual deterrence between Hizbullah and the IDF along Lebanon’s southern border. That, despite all the attempts that Washington and it allies have made to defang Hizbullah through various political means.

(You can read my longer account of the 2006 war here, or my earlier account of the growth of Hizbullah here.)

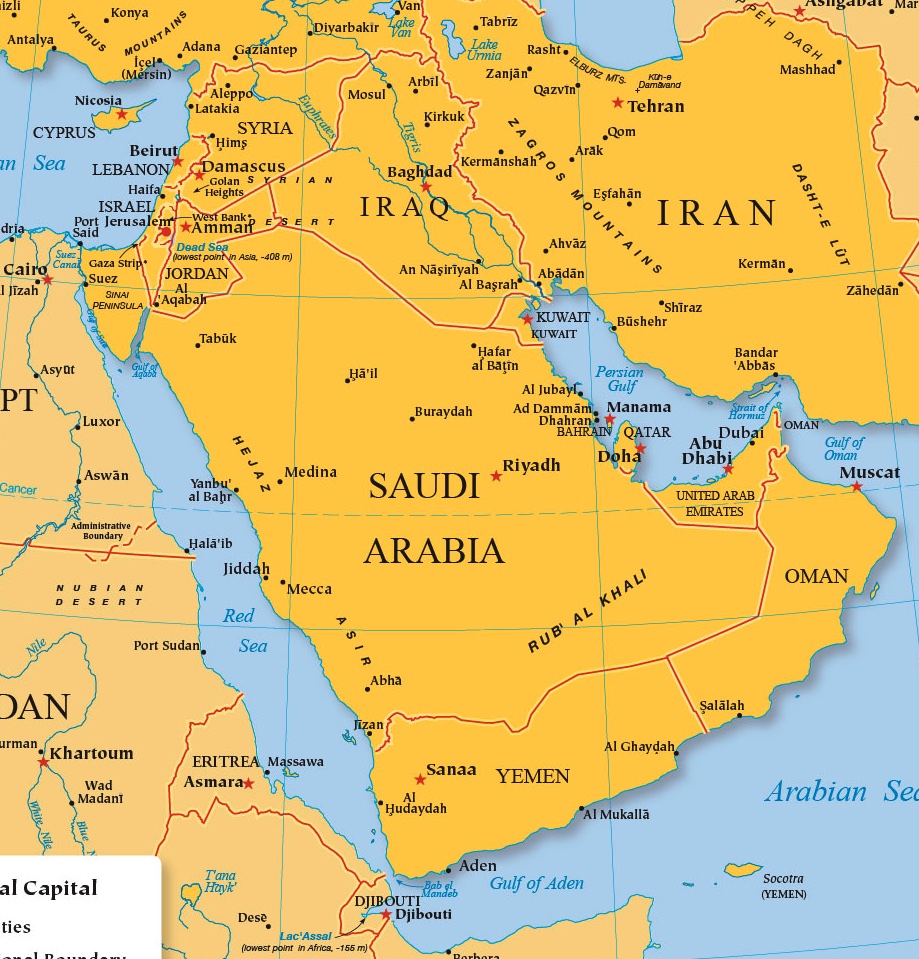

West Asia’s current vortices of “deterrence”

So now, let’s take a quick look at the many inter-swirling vortices of military “deterrence” within today’s West Asia, and the effects thereon of the injection of additional American military forces. Hold onto your seat. This gets complex, fast.

First, Israel until recently relied on massive, threats of a (repeat) application of the highly escalatory “Dahiyeh Doctrine” against Gaza to deter the Hamas military leaders from launching any operations against Israel—at the same time that by all accounts they were relying on economic pacification to deflect Hamas from wanting to do any such thing. The economic deflection did not work. And thus far, the Dahiyeh Doctrine has not worked either. (As, indeed, it did not in the actual Beirut Dahiyeh back in 2006.)

The potential for either a lengthy continuation of Israel’s current delivery of huge amounts of death and destruction against Gaza from stand-off platforms (air, sea, or air), or for a large-scale and quite likely highly escalatory ground invasion, certainly remains. Paradoxically, some forms of a ground invasion might inflict less damage on civilians in Gaza than a continuation of stand-off bombing.

Israel is also currently relying on threats of massive retaliation to deter Hizbullah from launching any significant escalation from Lebanon.

Various Iranian leaders have warned that if Israel moves ground troops into Gaza, then “Hizbullah’s fingers are on the trigger” in Lebanon. That is a classic projection of deterrence.

But then, U.S. leaders have warned both Hizbullah and Iran since last week, that if they take any action against Israel (or against the U.S. military presence that is widespread in many parts of West Asia), then “they will regret it”, etc. Those are also classic deterrent threats.

Yesterday, there were reports that Iran’s allies in Yemen’s Houthi movement had taken some low-grade military actions against Israeli assets, apparently in or near the Bab al-Mandeb Strait at the south end of the Red Sea—and also, reports that the significant pro-Iranian militias in Iraq had launched drone attacks against at least one of the U.S. military bases in their country.

None of those reported actions seemed to have caused many casualties, if any; and they did not immediately escalate further. But they almost certainly served as warnings from the pro-Iran side that, in the event of an escalation in Israel’s immediate vicinity (at either its southern or northern borders), then U.S. and Israeli assets throughout a broad swathe of West Asia could be at risk. They thus served amply to back up Iran’s clearly communicated posture of deterrence.

Where is diplomacy?

To be honest, the above listing of deterrences in West Asia is far from complete. I haven’t mentioned Syria there (which had two big airports bombed by Israel last week), and I haven’t mentioned the potential for radical political upheavals to occur in the region, which could change many of the strategic calculations governments are currently making.

However, it is clear that by inserting additional numbers of its own troops and naval vessels (including aircraft carriers) into the region, the United States is definitely increasing its linkages to the conflict(s) in the region both qualitatively and quantitatively.

During Pres. Biden’s visit to Israel on October 18, much was made of the fact that both he and Secretary of State Blinken had actually sat in on meetings of Israel’s war cabinet. This is a far, far closer degree of U.S. entanglement in an Israeli war than has ever been seen before. Several Israeli and Western reporters (including the NYT’s Steven Erlanger here) have written that this close U.S. involvement in the conduct of Israel’s war in Gaza unsettles many Israeli commentators, who fear Washington may act to constrain the decisionmaking of Israel’s leaders. It should most certainly unsettle the American citizenry, since it ties our country unprecedentedly closely to the course of a conflict of quite unpredictable proportions.

And it does this at a time when there is zero U.S. diplomacy visible to the public that aims for de-escalation or better yet a complete Gaza-Israel ceasefire, such as could and should be monitored by a high-level U.N. monitoring body. Indeed, as we learned last week, State Department employees were as of then—and apparently still until today—under orders not to even mention terms like “ceasefire” or “de-escalation” in their public utterances regarding Gaza.

This craziness has to end. The United States has no business raising global tensions in this perilous way. We as U.S. citizens need to add our voices to those of peoples and leaders all around the world who are calling clearly for a complete ceasefire in Gaza and speedy attainment of a resolution to the underlying Israeli-Palestinian conflict on the basis of long-existing U.N. resolutions.

35 years ago, the world finally breathed a sigh of relief when leaders in Washington and Moscow realized that ending the situation of Mutually Assured Destruction through negotiations was far and away preferable to omnicidal nuclear annihilation. Today, the situation in West Asia is poised on a new knife-edge that (with or without the use of nuclear weapons) threatens the Mutually Assured Destruction of much of the political map in that long-troubled region. This is the MADness that has to end. Ceasefire and far-reaching peace negotiations are the only path out.

great analysis and insights.