The death of former U.S. President Jimmy Carter feels like the end of an era– and all the more so, since it will be followed very speedily by the launch of the Trump/Musk presidency.

There has been much discussion about the echoes between Carter’s failure to win re-election after his first term back in 1980 and the crash-and-burn that doomed Pres. Joe Biden’s more recent, far too-long-pursued attempt to win re-election. The reasons for the two failures were very different. Age, which was the major factor (of many) for Biden certainly wasn’t a factor for Carter. The explanations most U.S. commentators have given for Carter’s resounding failure back in the elections of November 1980 have nearly all centered on his failure to resolve the lengthy and very debilitating crisis over Iranian students’ holding of U.S. hostages and the (linked) issue of the massive disruptions that the collapse of the Shah’s regime in Iran inflicted on the U.S. economy.

But by contrast, very little attention has been paid to the significant effect that Sen. Ted Kennedy’s decision to run against Carter in the Democratic primary much earlier in 1980 had in weakening Carter’s ability to organize a successful re-election campaign. And crucially, the role that dedicated pro-Israel organizing played in encouraging Kennedy to mount that primary challenge to Carter.

Back in 2009, I secured and was able to report on a short series of interviews with the Kennedy staff member who had been the linchpin of that pro-Israel organizing effort. That was Tom Dine, a man who in 1979 joined Kennedy’s staff in the senate after some years working for the Senate Budget Committee and as a defense-affairs staffer for Sen. Edmund Muskie. “With Ted Kennedy, I was ostensibly doing defense policy, but really I was orchestrating his Jewish-vote efforts,” he told me during those interviews.

With his hiring of Dine, the senator’s preparations for the presidential bid would go into high gear.

In this 2019 article in Vanity Fair, Jon Ward provided some intriguing background about Kennedy’s decision to run for president, focusing on the fact that the legacy, achievements, and fate of his two older brothers, JFK and RFK, weighed very heavily on him. Kennedy had been in the Senate since 1962. In 1972 and 1976 he had been reluctant to run for president because of the lingering stain from the Chappaquiddick incident of 1969, which resulted in the late-night death of a young woman riding alone with him in his car. But as Carter’s presidency continued, Kennedy increasingly felt that he might be able to put Chappaquiddick behind him and run in 1980.

In December 1978, he made an early, attention-grabbing big move, through his intervention at an unusual “midterm convention” that the Democratic Party bosses convened in Memphis. By then, Ward wrote, there was already considerable discontent in the party’s grassroots with Carter’s performance. Among the strongest gripes was the fact that Carter, a fiscal conservative, resisted calls from the base to establish a national health-care system– something for which Kennedy was a strong advocate.

At the Memphis convention, Carter gave an “unremarkable” presidential address. Ted Kennedy did not have an individual speaking slot, but he took part in a panel discussion on health-care, and according to Ward he completely wowed the audience. (That panel was moderated by the young governor of Arkansas, a complete unknown called Bill Clinton.)

Throughout the first half of 1979 Kennedy–who was Chair of the powerful Senate Judiciary Committee– and the president continued to tussle publicly over health-care. Meantime, Kennedy continued building nationwide support for a possible bid. By late summer he had made a definitive decision to run in the following year’s primary against Carter. He made the final announcement of his campaign in early November 1979. Tom Dine was one of the key people he brought in to help run the campaign. Here’s what I wrote in my 2009 profile of him:

Dine worked hard for Kennedy: “It was in the course of that campaign I met the organized Jewish community…. They were the kings in every city!” The campaign was troubled from the start, but in March 1980 Kennedy won a surprise victory in the New York primary. By all accounts, that win was propelled by the support he got from the Jewish community–particularly after Carter’s UN ambassador failed to protect Israel from a Security Council vote denouncing its West Bank settlements.

Meanwhile, another potential employer was also knocking at Tom Dine’s door: the board of the increasingly powerful pro-Israel lobbying group AIPAC offered him the job of Executive Director. “I said I would go with [Kennedy] as far as it goes,” Dine recalled. “Then in July or so, Carter gets renominated…. And I said yes to AIPAC.”

Carter and Kennedy fought hard during the months of state-level party caucuses and primary elections that were held, starting in Iowa in late January 1980… By early June it was finally clear that Carter had won enough delegates to win the nomination.

But Kennedy limped on. When the Democratic Convention was held in mid-August in New York’s Madison Square Garden he made an bid to change the rules so that delegates would not be bound by the results of their state-level primaries. That failed, and the convention then confirmed Jimmy Carter as the party’s candidate for November.

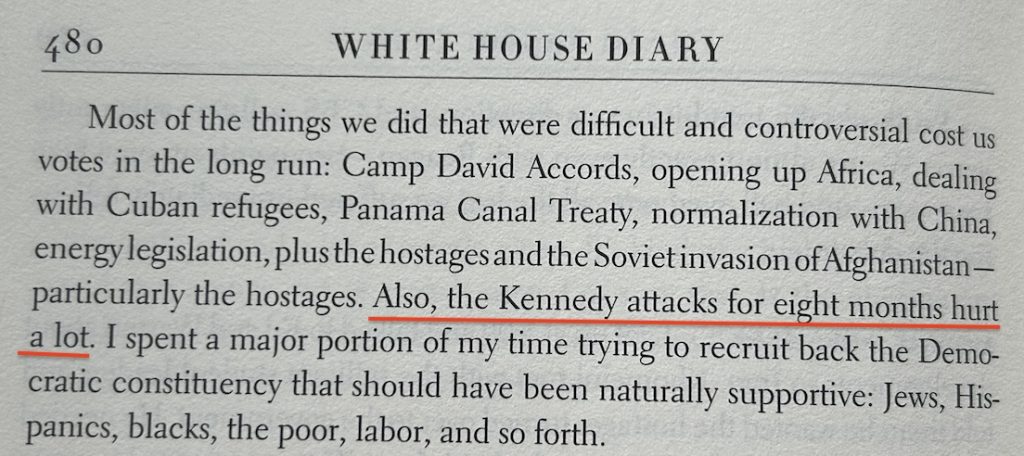

Kennedy conceded Carter’s victory at the convention only grudgingly. But those months of tough intra-party wrangling had already contributed significantly– along with the other factors like the burning hostage crisis, the economic woes, and so on– to weakening Carter’s political standing as he entered the last weeks of the general election.

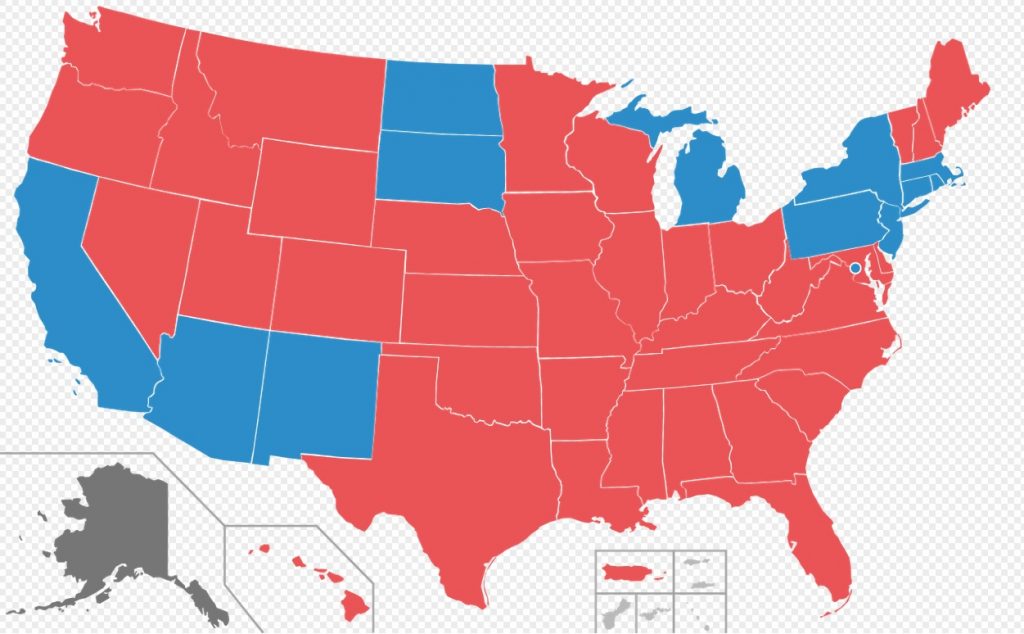

That election was held November 4. Even before polls closed in California it was clear to Carter that he had lost. In the annotated version of his White House Diaries that he published in 2010, Carter wrote of his defeat that day:

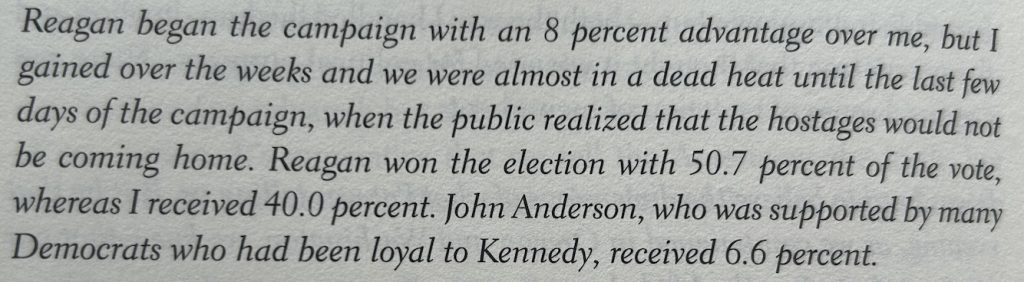

On November 5, he noted these numbers in his diary:

Ten weeks later, he returned to his hometown of Plains, Georgia.

Tom Dine, meantime, was settling comfortably into his new position as Executive Director of AIPAC. He speedily built a close relationship with Pres. Ronald Reagan’s Secretary of State, George Shultz. During my conversations with Dine in 2009, he told me he had many fond memories of the Saturday mornings when he used to sit one-on-one with Shultz, by the fireside in Shultz’s office on the seventh floor of the State Department, conferring closely–no aides present–on key aspects of US Middle East policy, “especially arms sales.”

Early on in Reagan’s first term, his administration had had one public spat with Israel. In his 2009 conversations with me, Dine recalled that in 1981 he had fought hard to block a sale of US-made AWACS planes to Saudi Arabia. He narrowly lost that battle.

“[B]ut you never really want to have this kind of confrontation,” he told me. “It’s not good for the executive branch, not good for the legislative branch and probably not good for AIPAC.”

George Shultz was apparently convinced by that argument and started hosting those quiet Saturday one-on-ones with Dine. “We’d talk about future arms sales so it would never come to that confrontation again,” Dine said. “It was one of the nicest things that ever happened to me, associating myself with George Shultz.” Did Dine talk about the administration’s proposed arms sales with people in Israel before he went to the meetings? “Sometimes, sometimes not. Definitely with people throughout the executive branch, and people on the Hill that I respected.”