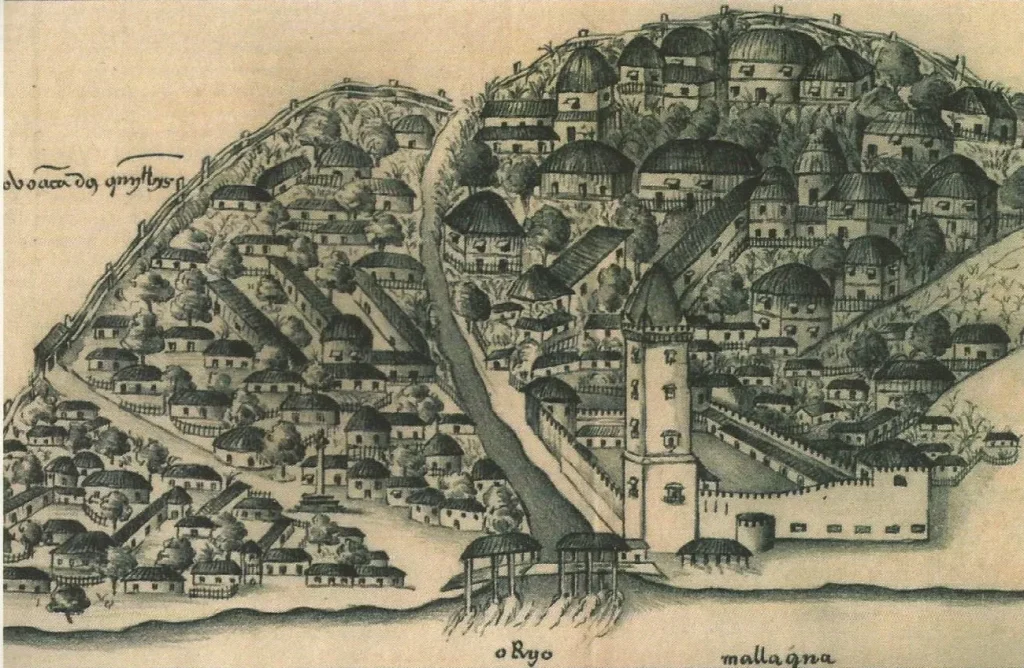

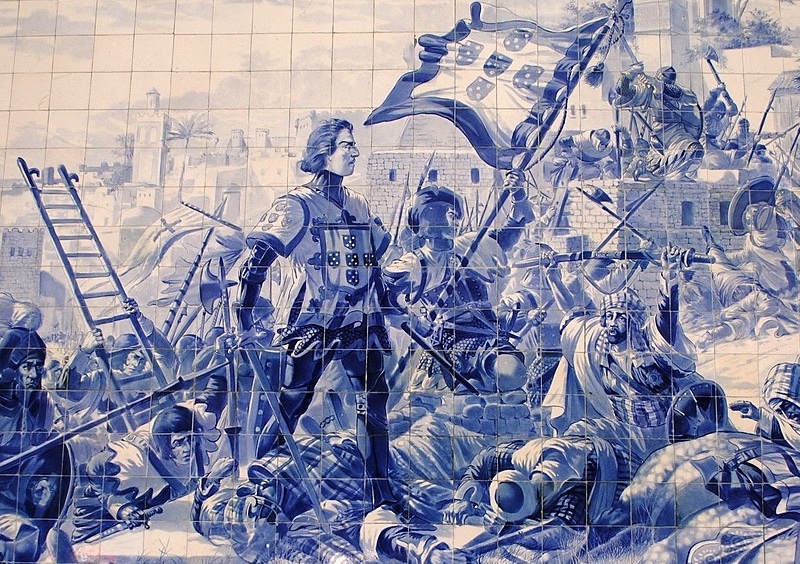

The painting above is of Portuguese conquistador Afonso de Albuquerque

For Pres. Trump, cruelty is a vital tool as he bulldozes through all constitutional requirements to undertake (and publicize) exemplary deportations of undocumented immigrants and of any legally documented visitors like Columbia University’s Mahmoud Khalil whom he arbitrarily chooses to punish.

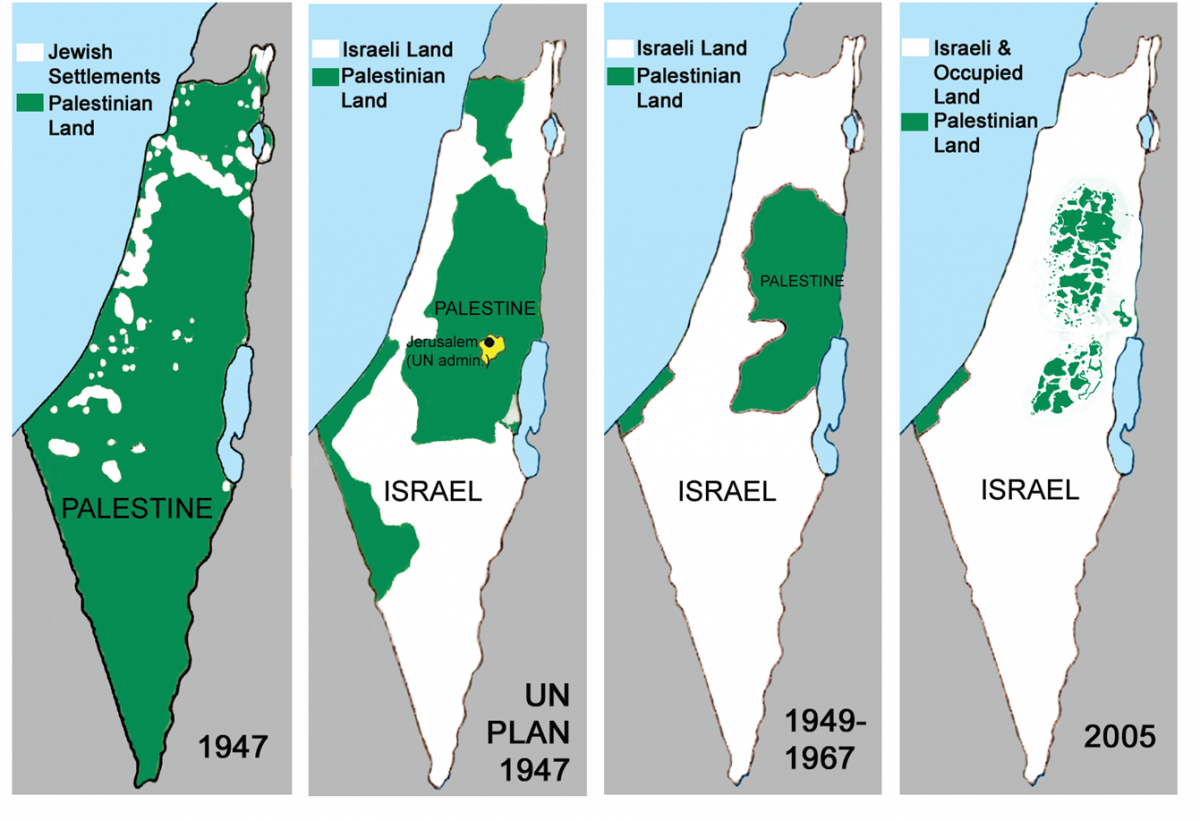

For Israel’s PM Netanyahu and his ministers, cruelty is similarly a vital tool as they deploy waves of bombers and incendiary drones against two million Palestinians huddling under tarps on Gaza’s trash-piled shores while totally blocking the entry into Gaza of all the basic necessities of life.

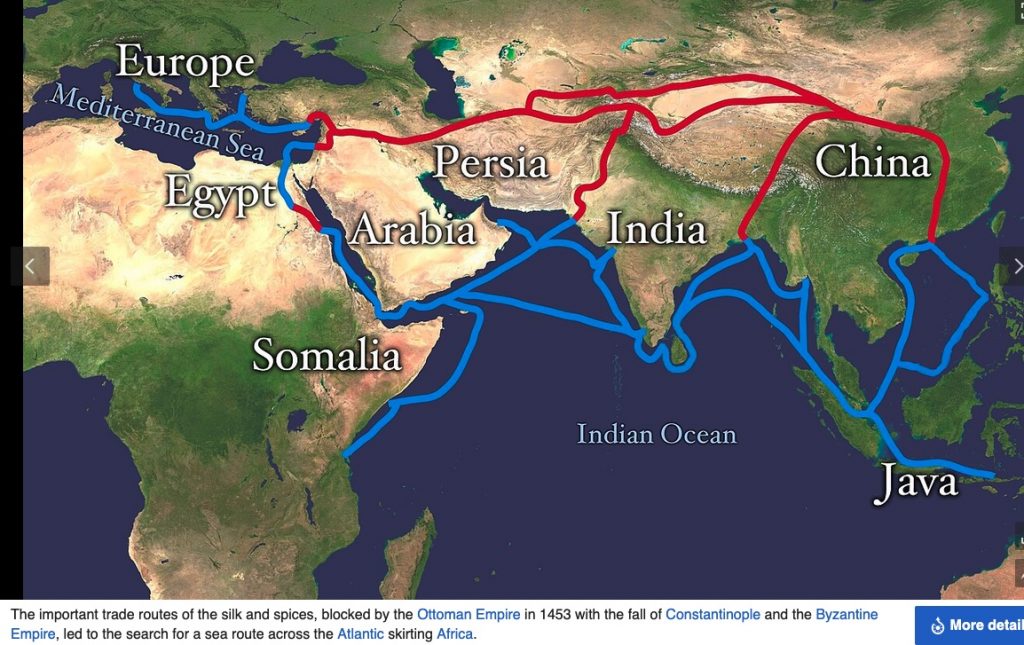

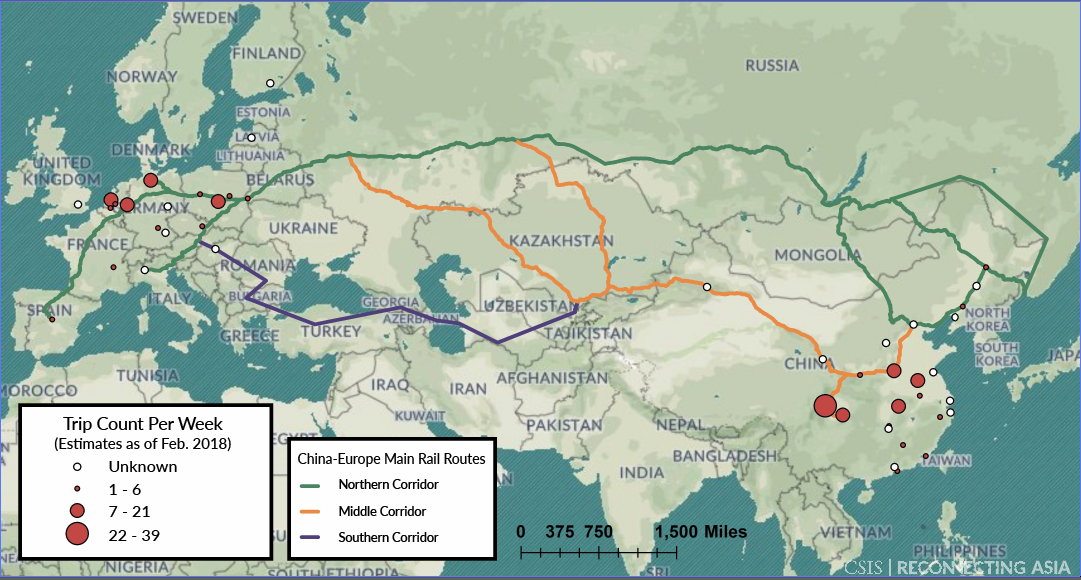

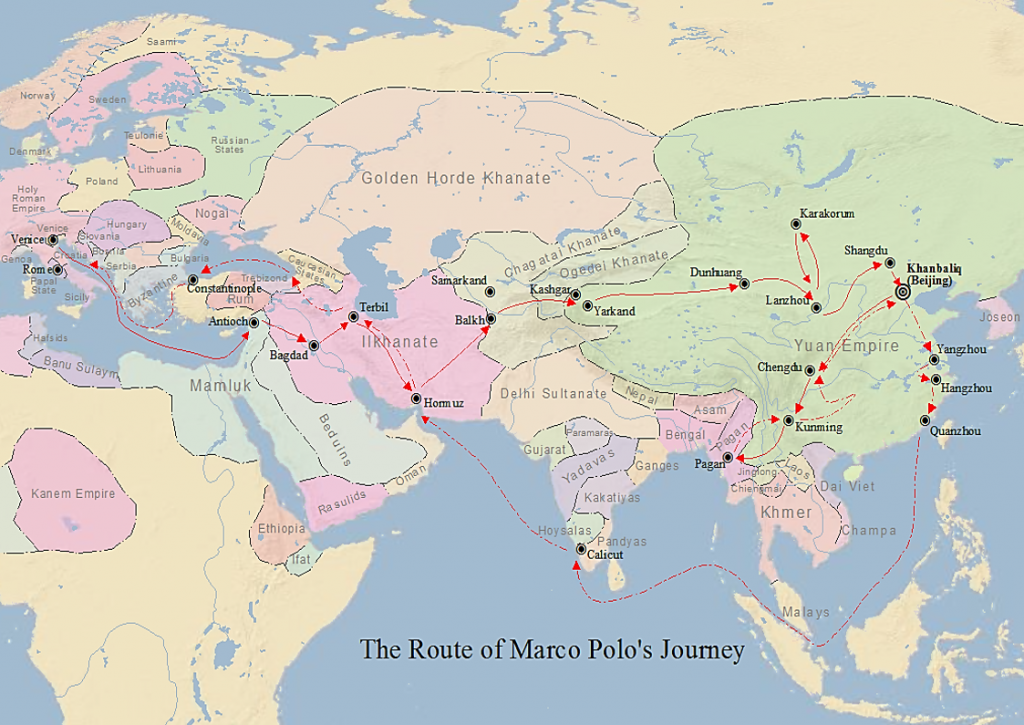

It’s worth noting that cruelty has been a vital, and deliberately deployed, tool for the architects and commanders of “White” empires ever since the 15th century CE. In 1415, Portuguese navigators started carving their way down the coast of West Africa to establish heavily fortified “trading” (plunder) posts in their quest for gold. Those navigators were also intent on finding a sea-route to the richest trading zone they’d ever heard of, the one that traversed the Indian Ocean and wove the riches of East Africa, India, and distant Cathay (China) into the most advanced manufacturing and consumption area then known to humankind…

Continue reading “For the commanders of Western hegemony, cruelty is a vital tool”