The high-profile former Meta exec Sheryl Sandberg headlined an event on this issue for the Israeli Mission to the U.N., December 4

Suddenly, a few days ago, and just as the Israeli military was resuming and indeed intensifying its operations in Gaza, Israel’s worldwide PR machine leapt into life with a large-scale campaign asserting as proven “fact” unproven claims that during the October 7 breakout from Gaza, the Hamas operatives had engaged in a broad campaign of rape and other forms of sexual violence against Israeli women.

What a coincidence. “Hey folks, don’t look at what’s happening to the civilians inside Gaza. Look over here instead!” (And a worrying proportion of Western media outlets did just that. Sigh.)

As a sometimes adventurous professional woman I’ve had to fend off a number of unwanted sexual advances over the years, on occasion a little forcefully. And I’ve done enough interviewing of survivors of rape and sexual violence in Rwanda and elsewhere that I well understand the grave harm that such acts cause. Obviously I would hate it intensely if my children or grandchildren were subjected to such harm.

But you know what? I’d hate it even more if they were killed. Murder is, I think, a very much graver harm than rape.

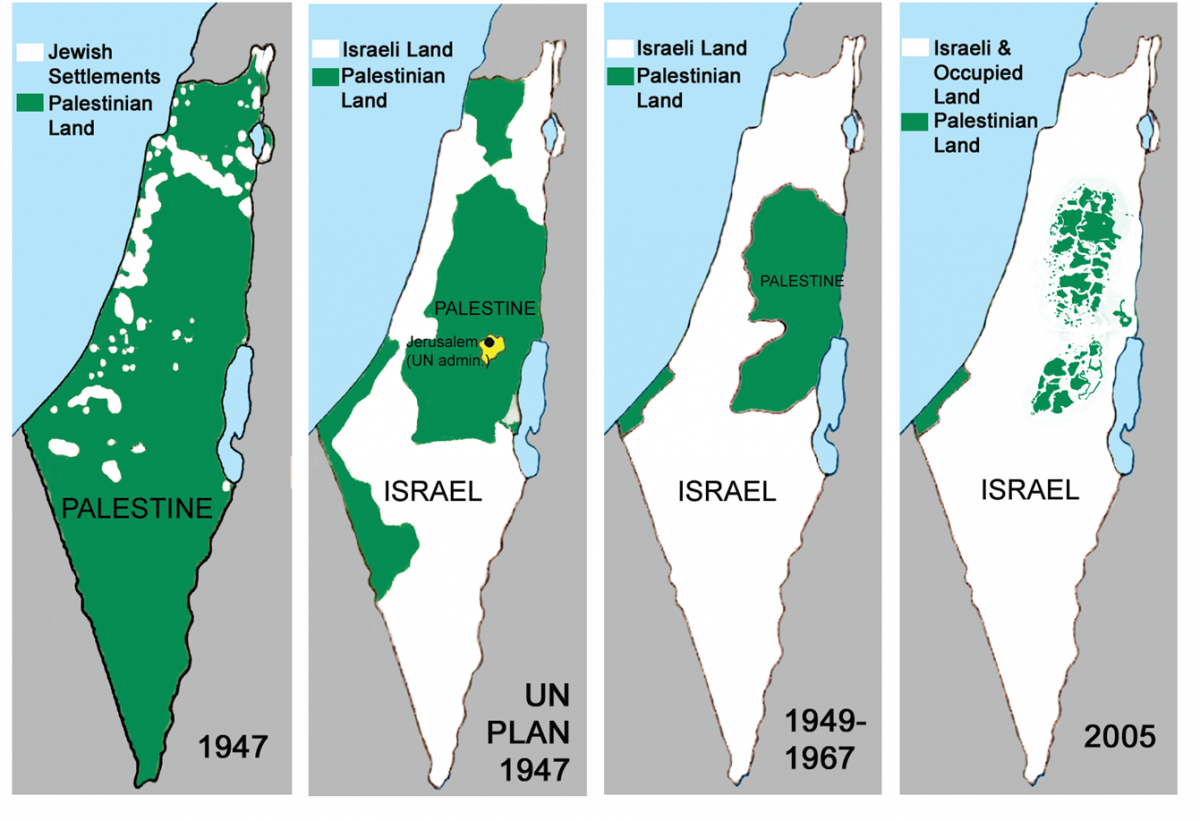

So first, a few facts. Al-Jazeera is now reporting that Israel has killed more than 17,000 people in Gaza since October 7. Most UN bodies estimate that about 70% of those killed are women and children. That would be ~ 11,900. Conservatively, let’s say that Israel has killed 3,000 to 4,000 women in Gaza. And those who are still alive are barely surviving amid the most God-awful circumstances imaginable.

Let’s think of each of those women’s lives lost or gravely harmed as being just as valuable as the lives of Israeli women?

And here are some facts and figure about the people killed in Israel during the Hamas-led breakout of October 7—which is what we can know about, with much more certainty than we can know about women (or men) who may have been subjected to sexual assault.

Continue reading “On claims of rape during Hamas’s October 7 breakout from Gaza”