(Charlton Heston as Marc Antony, giving “Cry Havoc!” speech)

The war in Ukraine continues to have a devastating impact on our already troubled world, including on the global flow of grains and other essential items and on the integrity of our global governance system. It drapes the shadow of possible nuclear annihilation across the whole globe… So it’s great to see that a growing number of mainstream voices here in the United States are now voicing support for a speedy ceasefire in Ukraine. Last week, the Rand Corporation published this short-ish study by Samuel Charap and Miranda Priebe. And The Economist published this piece (paywalled) by Christopher Chivvis, who heads the Carnegie Endowment’s American Statecraft Program.

Both these articles have enriched the public discourse significantly. However, neither goes as far, or is as clear, as I think is needed. (You can read my first critique of the Rand piece here.) Specifically, I think that any calls for a speedy ceasefire in Ukraine need to address the larger issue of the need for a U.S.-Russia détente in Ukraine.

So what are the chief impediments here in the United States to reaching a pro-ceasefire policy, pro-détente policy and how can these impediments be overcome? I see these impediments as falling into three main categories:

- The (very often irrational) passions stirred up by any war, including this one.

- The hard interests of all those sectors, within and beyond the military-industrial complex, that profit from a prolongation of this war.

- The stunning dearth of diplomatic imagination, commitment, or expertise here in Washington DC.

Here is how I see these factors as operating:

The passions of war

When William Shakespeare was writing Julius Caesar, the society he lived in was deeply intimate with the horrors of war. It’s worth reading the whole of the speech in which he has a grieving Marc Antony call out, “Cry ‘Havoc!’ and let slip the dogs of war.” I’ve lived for several years in a war-zone and done field research in other societies reeling from the shocks of recent conflict. I know that during a war, passions can become easily inflamed—often to the extent of befuddling rational thought. (“Havoc” is a very great word for this.) And you don’t even have to live in the war-zone to be affected. Partisan supporters living far away can sometimes become even more tightly caught up in the passions of war than those who live in the war-zone.

The over-arching frame of pro-war discourse is usually a simple morality play of “good vs. evil”. Americans may, for various reasons, be particularly susceptible to the hyper-moralistic binaries of war-time passions. But Europeans and probably everyone else whose country has been at war also love to see their country as starring in a good morality play. European empire-builders of past centuries would talk at length about their wars bringing Godliness and “civilization” to the evil and benighted residents of the Global South…

Then in the early twentieth century, when the British and French were fighting in Europe against the Germans, British newspapers and politicians circulated numerous, deeply shocking “reports” about the Germans’ depravity… But a decade later, Labour MP Arthur Ponsonby compiled and published a very convincing rebuttal of many of those accusations. His book was titled Falsehood in War-Time, Containing an Assortment of Lies Circulated Throughout the Nations During the Great War. It is still worth reading. (You can learn more about the book—and see the “War Lies Bingo” game I created, based on some of his conclusions—here.)

Ponsonby wrote about the huge role that the British media of that era played in keeping alive, and very often exaggerating or even fabricating, the stories of German depravity that kept England’s pro-war passions running high. (He also noted that, prior to the U.S. entry into the war, U.S. journalists were much more assiduous in checking out the claims of German atrocities, and often rebutted them very clearly in their reporting at the time.)

The experiences of WW-1 are relevant in numerous ways until today. Historian Philip Zelikow noted in this recent book that by April 1916, the leaders of Britain, France, and Germany had each concluded that their side could not win that slogging meat-grinder of a war. They were all eager to end it. But none of them wanted to be seen by his own public as undermining the morale or bravery of the men then dying in their hundreds of thousands in the trenches of northern France.

So they all felt obliged to maintain a strong public facade of optimism about the prospects of imminent victory on the battlefield. They all pulled back from the hesitant, early explorations they’d undertaken of a possible U.S. role in mediating a ceasefire…And thus, the killing continued for a further 30 months.

The interests of sectors that profit from a prolongation of war

I hope we’re all well aware of how much the big U.S. weapons manufacturers have been profiting from the war in Ukraine? One example: Lockheed Martin. As Eli Clifton noted in this recent report, Lockheed CEO James Taiclet boasted on a January 24 earnings call

about how the company handed $11 billion over to shareholders in 2022 via share repurchases and dividend payments, creating “significant value for our shareholders.”

Taiclet… said that Lockheed, the world’s largest weapons firm, was “ending the year with a total shareholder return of 40 percent.”

Clifton underscored that, “those stock buybacks, dividends and appreciated stock value are largely underwritten by U.S. taxpayers. The company’s 2021 annual report acknowledged that, ‘…71% of our $67.0 billion in net sales were from the U.S. Government’.”

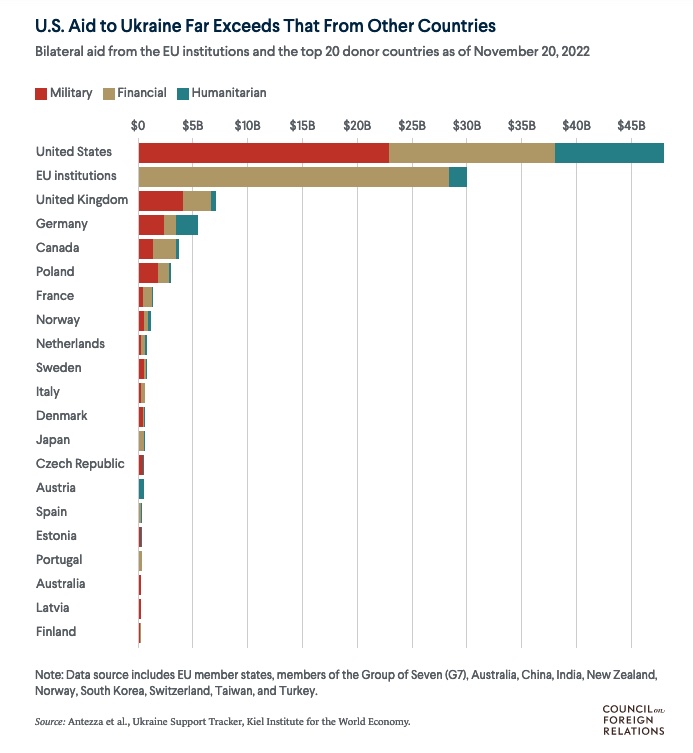

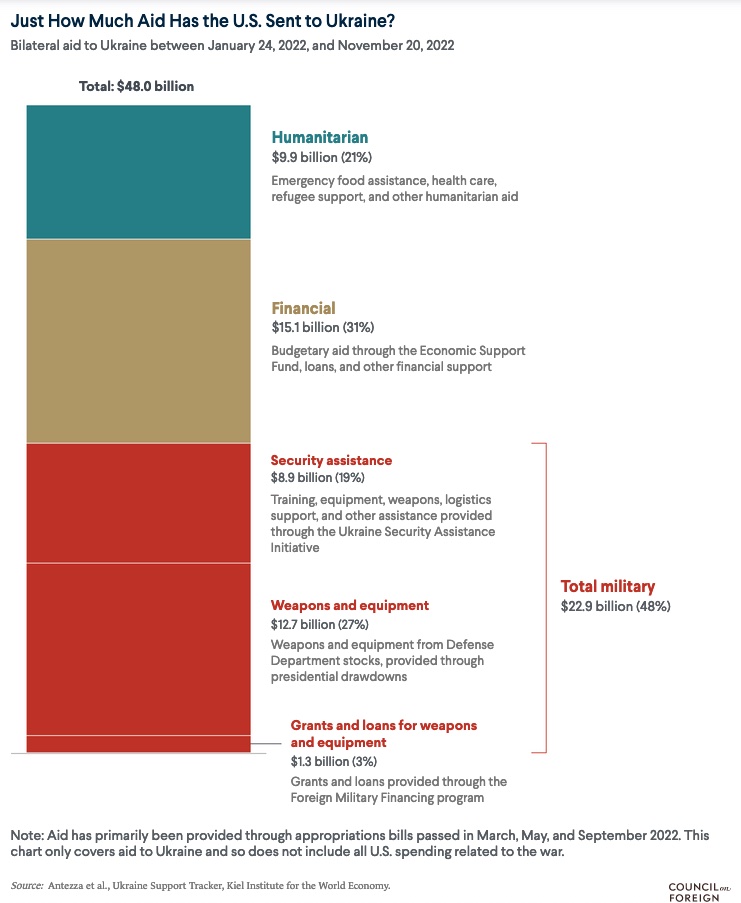

Regarding the total aid that Washington sent to Ukraine during the first nine months of the war, the Council on Foreign Relations has produced six handy charts, here. The one I use here shows that through November 20, U.S. taxpayers sent military aid worth $22.9 billion, financial aid worth $15.1 billion, and humanitarian aid worth $9.9 billion to the country, for a total of $48 billion.

That $48 billion ran through November 20. We taxpayers are currently obligated to cover a total of over $100 billion in aid to Ukraine.

People! This is money that could and should have been used for much more productive purposes. Like: supporting schools, housing, hospitals, and infrastructure here at home… helping low-income countries of the Global South deal with their multiple economic crises… or paying down our country’s national debt…

And it is not only the military-industrial complex that has been profiting grotesquely from the war. It is also the whole of the rest of the MICIMATT complex, as so aptly defined by Ray McGovern. The “M” in the middle of his acronym is the media. Today’s corporate media sure love them a good war, which can bring them millions of avid eyeballs on a silver platter. Today’s multi-media war coverage is light-years more “vivid” and more “viscerally engaging” than the staid old newspapers of Ponsonby’s era. But the business plan is basically the same as what he recorded then: to deliver as many eyeballs as possible to the advertisers. The maxim is still, far too often, “If it bleeds, it leads.”

Full disclosure: When I was starting out as a journalist in 1975, my career profited greatly from the outbreak of Lebanon’s civil war. I was getting front-page onto major newspapers in the U.K and U.S. when I was just 23!

But in Lebanon as in any war-zone, it was clear that many other sectors beyond the military-industrial complex were profiting hugely from dragging out the war. Lebanese comedian Ziad Rahbani would joke that purveyors of window glass and black clothing were also making out like bandits. That’s not wholly a joke. Post-war reconstruction can also be a super profit center. (But before you can access it, you have to have all that destruction of the war itself.)

The dearth of diplomatic imagination, commitment, and expertise

Ever since 1991, the United States has stood astride the world system like a colossus, unchallenged until recently in any fundamental field of human endeavor. This enabled Washington to launch “wars of choice” wherever it chose—that is, wars that were far from existentially “necessary” for the survival of the United States. It did so because it could: in Kosovo, Afghanistan, Iraq, Somalia, Syria, and many other countries. (Americans were told, among other things, that these wars would greatly improve the lives of the peoples of the countries targeted. The tragic evidence we have today belies that claim.)

Washington’s hegemonic position in world affairs, and the strong bias it has maintained for three decades now in favor of military over diplomatic instruments, has left most of the country’s political elite bereft of any real depth of diplomatic expertise or imagination. Acquiring a nuanced understanding of the interests and views of other parties (including opponents), or the ability to “think outside the box” by exploring a broad range of different diplomatic options: skills like these have withered on the vine of a political elite that, inside and outside the halls of governance, is fed and watered overwhelmingly by the donations of massive military contractors.

Hence, though I was glad to read the recent articles by Chivvis and Charap & Priebe, I was disturbed at the paucity of the specific political changes they proposed. The furthest that Chivvis would go was to suggest that “the West” should engage in “tough conversations to persuade Ukraine to adopt a more realistic approach to its war aims.” In other words, the governments of the United States and other Western nations should still subordinate their policies to the whims and preferences of the government in Ukraine, rather than asserting their right to pursue their own interests as they define them. That, despite the shoveling of all those billions of dollars of aid from the United States and other NATO countries: aid on which the Ukrainian government is now completely reliant.

Regarding our aid to Ukraine—like our aid to Israel, which is now dwarfed by that sent to Ukraine—we who are U.S. taxpayers certainly have the right demand a clear accounting of what it achieves. And if its current main function is to prolong a war that could be halted through a negotiated ceasefire, then we need to take responsibility for that, too.

The main advantage of Charap & Priebe’s study over Chivvis’s is that they acknowledge the clear possibility that on some key issues the interests of Kyiv and Washington may diverge. And they argue that in these cases—which include the question of whether Kyiv should aim to regain all of its pre-2014 terrain by force—Washington should be prepared to pursue its own interests. They urge that Washington do this by pushing for a negotiated halt to the fighting, rather than by endlessly (and very expensively) propping up a Ukrainian war effort that is increasingly not in the interests of the United States.

So far, so very laudable. (Reminder: You can access their study here. And my quick digest and first take on it was here.) The authors then proceed—as I am doing in this essay—to try to identify the impediments to a negotiated ceasefire and to explore how those can be overcome. It is at that point their analysis starts to come undone, displaying the following weaknesses:

- They portray the conflict as primarily one between only Russia and Ukraine, with those two parties involved in complex bilateral “signaling” regarding their readiness for a negotiation. They portray the United States and its NATO allies as standing outside the conflict and able to influence its course only indirectly, by promising incentives or disincentives to the warring parties. This is analogous to the position Washington has adopted towards numerous other international conflicts over recent decades, including the Arab-Israeli conflict. However, the engagement of the United States and its allies in the conflict in Ukraine, on the anti-Russian side, is considerably deeper and more partisan than their engagement in any of the Arab-Israeli wars has ever been. In Ukraine, it is impossible for the United States to present itself as a “neutral”, external observer, able to impartially adjudicate the rights and wrongs of various actions and steer the warring parties towards a settlement.

- Because of the above, Charap & Priebe fail to even start to examine—as I have been doing here—what the impediments in the United States to a achieving a negotiated halt might be. They seem to assume a calm and generally benevolent degree of American rationality, unbuffeted by the swirling tides of anti-Russian popular passions and unaffected by the blandishments of the big weapons manufacturers. But if, as I maintain, the U.S. government can and absolutely should play a big role in achieving a negotiated halt to the fighting in Ukraine, then those factors affecting U.S. domestic policies have to be clerarly identified and confronted.

- The authors seem to have a very U.S.-centric view of the world. The United States and its NATO allies are the only “external” (that is, non-Ukrainian, non-Russian) actors that they view as being able to affect the diplomacy around this conflict. They give a quick nod to the role that NATO member Turkey played in convening earlier rounds of talks between Russia and Ukraine. But they do not even entertain the idea that any non-NATO actor could play any potential role at all in achieving a ceasefire. And that even includes the United Nations! In my view, if we are serious at all about the urgency of a ceasefire in Ukraine, then we should be proactively exploring what the United Nations and other “external” actors—and yes, that could include China, South Africa, Switzerland, and a range of other countries, as well as the United Nations—might be able to do to help achieve that.

How to overcome the (domestic-U.S) impediments to a ceasefire

The goal here is to win U.S. governmental support for a ceasefire, but the chances of this happening will be radically increased if we can build strong, nationwide support for it. This means we need to understand the phenomenon of the popular passions that have been running strongly in support of the war since last February (though it’s true that there has been a reduction in this support in the past few months, which is very welcome news.) And then, we should explore how we can further reduce or redirect these passions.

I propose that antiwar, pro-ceasefire activists explore these kinds of questions:

1. Who benefits from the prolongation of the war?

The obscene profits being reported by Lockheed should certainly be in the spotlight! But it would be great to see a lot more reporting on the activities of the rest of the military-industrial complex, including on its members’ donations to political figures and think-tanks… and to see that reporting widely distributed, preferably alongside reporting on the continued, chronic underfunding of basic domestic needs.

2. What is so special about Ukraine?

Millions of people in countries around the world are suffering from armed conflict. My heart aches for people in Myanmar/Burma, Congo, Palestine, Somalia, and elsewhere as much as it does for Ukrainians. But why should my taxes go so disproportionately to provide aid to victims of aggression in Ukraine, rather than war victims in those other places? (Especially when it is not clear at all that the forms of aid Washington has sent to Ukraine have improved the lives of Ukrainians, rather than prolonging their suffering.) Is there something special about the suffering of Ukrainians rather than that of other peoples who happen not to be “White”? We should be prepared to ask this question.

3. Why should we believe the reporting and analyses of Ukraine voiced by figures who helped lie us into the war in Iraq?

Back in 2002-03, Joe Biden was a prominent member of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee who accepted all the skewed intel the Bush administration gave him about alleged “WMDs” in Iraq, and voted in favor of an invasion that was in violation of international law. (Later, he was even a prominent advocate of splitting Iraq into three separate parts.) That invasion was also actively pushed for by prominent journos at The New York Times and other pillars of the “liberal” media.

This time round, at least Pres. Biden speaks somewhat cautiously about the risks of escalation in Ukraine. The New York Times, much less so. And the content of news coverage there and in nearly all the corporate media dwells at length on the suffering of people in government-held parts of the country while saying nothing about that of residents of the secessionary eastern provinces.

4. What kind of a ceasefire should we push for?

Any ceasefire that halts the fighting will save lives and lay a foundation for a deeper peace. We should push for a total, countrywide ceasefire that contains clear constraints on the ability of the warring parties to resume the fighting, that is, an armistice. In 1953, the United States (then acting on behalf of a U.N.-based fighting coalition), China, and North Korea all concluded an armistice in Korea that has remained in place since then.

As I noted in this recent essay, South Korea, which was a U.S. ally heavily dependent on U.S. aid, never agreed to sign that armistice; but Washington decided to go ahead and sign it anyway, and since then has taken responsibility for South Korea’s compliance with its terms. I also noted that, over the 70 years since 1953, that armistice has proved extremely beneficial to South Korea (which still has not signed it, by the way.) A lesson for Ukraine is that Washington and NATO could and should consider seeking an armistice there with Russia that need not be dependent on the Kyiv government’s prior agreement. After the fact, with generous support from NATO/EU countries for the rebuilding of Ukraine’s economy, Ukrainians could benefit from an armistice as much as South Koreans have.

5. How can we get to an armistice?

The peacemaking model that’s implicit in the Charap/Priebe study seemed to be built on the idea that Russia and Ukraine are the two parties that need to conclude a ceasefire, while Washington could play a helpful role as a mediator. As I’ve argued above, I think that model is unhelpful. I think a better description of the conflict in Ukraine is that it’s one in which the key decisionmakers are located in Washington and Moscow. These are the two parties that are capable of arriving at, and then later abiding by, a ceasefire. So it is really a U.S.-Russian détente over Ukraine that is needed.

The question is, how can we achieve this? Let’s hope that this time round, unlike in 1962, we don’t need to have a major nuclear-weapons crisis between these two powers to get this process started. And this time round, unlike in the 1960s, we have a much more multipolar world, in which there significant world powers other than Russia and the United States that (a) have a very strong interest in seeing the avoidance of a nuclear crisis over Ukraine as well as real moves toward a U.S.-Russia détente there, and (b) have real heft in world affairs.

All of us here in the United States who want to avoid a nuclear crisis in Ukraine and build a U.S.-Russia détente there should be working to build coalitions with governments and institutions around the world who share our goals. It’s true that the anti-war, pro-ceasefire constituency here in the United States is still only a minority of the national population (though hopefully, one that will continue to grow.) But the population here the United States is still only 5% of the total of humanity. We should openly embrace the many chances we have to work with a variety of governments and other institutions from outside the U.S.-led “West” in order to win the armistice and the broader U.S.-Russia détente that the whole world—including the Ukrainian people—now so desperately needs.

Détente is certainly preferable to nuclear destruction – the way events are moving. As Helena asks: how can it be achieved? My own personal view, for what it’s worth, is that the protagonists must realize that World War Three is inevitable without a change in direction, and that those teleological philosophies that claim a peaceful outcome will emerge from continued conflict are dangerously mistaken – blind confidence contradicted by history.

https://patternofhistory.wordpress.com/