The above photo is from a meeting Pres. Putin had with PM Netanyahu in 2018, when they fine-tuned some arrangements for coordination (“deconfliction”) in Syria

On December 13, I made a first stab at analyzing some of the regional and global repercussions of the recent rapid disintegration of the Asad government in Syria– and indeed, also, of the Syrian state’s entire defensive capability, which Israel bombed to smithereens in the days (and hours) right after the collapse of Pres. Asad’s government on December 8.

Over the past week I have learned more, and I hope come to understand more, about the decision-making in Moscow that was a vital factor in Asad’s collapse– and also, about the possible effects of this collapse on the regional dynamics within West Asia, and on the worldwide balance of power in an era of rapid geopolitical change. In this essay I will sketch out some of my current thinking/understanding on these matters so crucial to the fate of humankind.

There were many factors, of course, that led to the collapse of the Asad government, as I had described in my Dec. 13 essay. But one absolutely crucial one is the decision that Russia’s Pres. Putin evidently made at some point in recent months to allow his longtime ally/protegé Bashar al-Asad to hang in the wind. (Some might say he stabbed him in the back…)

In today’s New York Times, Neil MacFarquhar describes Asad’s fall as constituting an “abrupt setback” for Russia. His lede was:

For decades, Russia has been trying to rebuild its influence in the Middle East. But after the rapid collapse of the Assad regime in Syria, the Kremlin is scrambling to salvage whatever it can.

Based on what I’ve been reading and seeing, I would challenge MacFarquhar’s assumption that Asad’s fall came as a surprise to “the Kremlin” and its master, Pres. Putin. It seems to me, by contrast, that Putin was a witting partner in the downfall of Asad: that he made the decision to allow (or even hasten) Asad’s overthrow even after his military and other strategic advisers had given him an extensive appraisal of the potential geopolitical downsides of that decision— logistical, reputational, etc. But he made his decision based on other criteria, which included an intriguing (and also very troubling) desire to coordinate pretty closely with Israel’s very hawkish designs against Syria, and also with Israel’s campaign against the Axis of Resistance as a whole.

Coordination between Russia and Israel in Syria is not, actually, a new phenomenon. Recall that throughout the past 14 months of the Israeli-US genocide in Gaza– and even, on numerous occasions, before then– the Israeli air force has made damaging and very destructive raids against targets deep inside Syria that the Israelis alleged served as key logistics or communications nodes for fighting units from Lebanese Hizbullah or the IRGC… And that the Russian units that provided vital area-wide air defense to all the parts of Syria that the Asad government held allowed those Israeli air-raids to proceed, as coordinated through the “deconfliction” mechanism the militaries or air forces of the two countries had established back in 2015.

However, for the Russians to stand aside while the Turkish-backed anti-Asad forces rampaged their way north-to-south throughout Syria starting November 27-28 required a whole new level of Russian complicity and coordination with many components of the region-wide anti-Asad coalition, including both Türkiye itself and Israel (and possibly also the U.S. military whose forces in eastern Syria were suddenly “revealed” two days ago to be twice as numerous as previously admitted.)

One of the best sources on Russian decisionmaking that I’ve been following has been John Helmer, an originally Australian journalist/analyst who has been reporting from Moscow since the late 1990s. (He and his late wife Claudia Wright earlier lived for some time in Washington DC, where I briefly met them in the 1980s. He and more especially Claudia were both quite close analysts of West Asian/ Middle East developments at that time.)

On his blog Dances with Bears, Helmer has recently published a string of reports that detailed many of the discussions inside Moscow on matters Syrian. Throughout these reports, he indicates that the General Staff gave plentiful warnings to Putin about the many dangers of failing to support Asad– but that he decided to do so anyway.

On December 12, Helmer wrote that,

Military sources in Moscow have told a tale of President Vladimir Putin’s decision not to defend the Syrian Arab Army and the Damascus government of Bashar al-Assad. That decision, the sources claim, was taken at least two weeks before the Turkish break-out from Idlib began on November 27, and was conveyed to Assad personally by December 6.

It had been hinted at four days earlier, on December 2, when Iran’s President, Masoud Pezeshkian, made an urgent telephone call to Putin. In principle, the Kremlin announced, Putin and Pezeshkian agreed on “unconditional support for the efforts of Syria’s legitimate authorities to restore constitutional order and maintain the country’s territorial integrity.”

In practice, there was a Russian condition. Putin told Pezeshkian that Russian anti-aircraft units in Syria would not operate against Israeli attack and defend the Iranian air bridge to Khmeimim for the troops and arms which Assad had been requesting urgently, and which the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps was ready to send. Putin also told the Iranian President that Russian ground forces and artillery would not engage Turkish forces moving southward, and would not bomb them from the air.

By the time Putin and Pezeshkian were speaking, after days of the closed-door debate with the General Staff, Putin believed he had the word of Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan and Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu that Russia’s principal military bases at Tartus and Khmeimim would not be attacked and Russian forces not threatened. Their pre-condition was that Putin would not encourage or defend Iranian reinforcements.

Indeed, there were reports that I’d read elsewhere, that said that after the Russians informed the Iranians that they’d decided not to support Asad, they also agreed to airlift out of Syria the several thousand IRGC troops who were then in the country, which they did via their air-base in Hemeimim.

There was also some apparently intense Russian (and Iranian) communication in those days with Türkiye, whose military and special forces have provided the main operational backbone for the anti-Asad coalition led by HTS. As a result of the Russian-Turkish communications the HTS forces have not interfered at all while the Russian military has been consolidating the military deployments in Syria that were previously quite far-flung. Indeed, I have seen several videos of HTS and allied forces cheering and “takbeering” enthusiastically as they stood aside to let small Russian military convoys make their way from other, smaller bases around Syria back to Hmeimim or to the Russian naval base at Tartous.

And a final note here on Putin and Israel. A Western colleague of Helmer’s in Moscow, Andrew Korybko, has published quite a lot of pieces on his Substack in recent years in which he has spelled out, as he did here on December 12, the degree to which–

Putin is a proud lifelong philo-Semite who never shared the Resistance’s unifying anti-Zionist ideology, instead always expressing very deep respect for Jews and the State of Israel. Accordingly, as the final decisionmaker on Russian foreign policy, he tasked his diplomats with balancing between Israel and the Resistance. To that end, Russia never took either’s side and always remained neutral in their disputes, including the West Asian Wars.

The most that he ever personally did was condemn Israel’s collective punishment of the Palestinians, but always in the same breath as condemning Hamas’ infamous terrorist attack on 7 October 2023. As for Russia, the most that it ever did was repeat the same rhetoric and occasionally condemn Israel’s strikes against the IRGC and Hezbollah in Syria, which Russia never interfered with. Not once did it try to deter or intercept them, retaliate afterwards, or give Syria the capabilities and authorization to do so either.

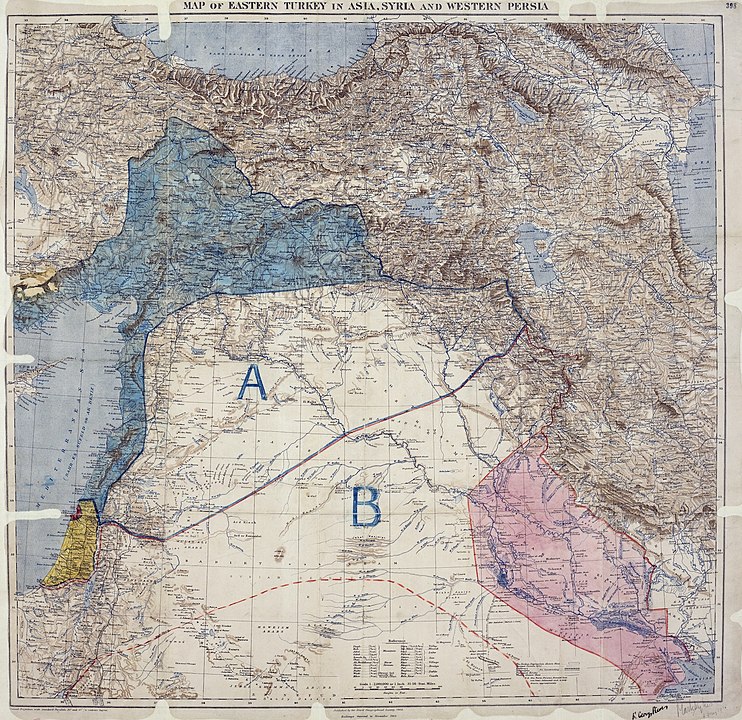

The new Sykes-Picot in Syria?

Before I get back to the West-Asia-wide or global dimensions of what’s been happening in Syria, let me take a quick look at the shape of what seems to be emerging in specifically the Mashreq/Levant.

Back in 1915-16, the British and French held intensive discussions over how, once they had achieved their hoped-for defeat of the Ottoman portion of the pro-German alliance in the World War then raging, they would divide up the specifically Mashreq portion of the Ottoman Empire between them. They set diplomats from each country, Mark Sykes and François Georges-Picot, to work to draw a line of demarcation between the two countries’ spheres of influence. And that demarcation line— with crucial amendments in the areas of Palestine and the rest of the Mediterranean coast-line– was more or less adopted into the post-war peace agreements.

There was considerable jockeying along the path of getting the (amended) Sykes-Picot agreement actually implemented. The people of the Syrian state that emerged from the peace agreements revolted energetically against the (British) idea that a militia leader they had imported from far-distant Hijaz– “King Faisal”– should be installed as their monarch. (So the British then shipped him off to be King of Iraq instead. They had full control there.) But the basic plan of having five nominally independent “Arab” states in this region, with Lebanon and Syria coming under French control, and Palestine, (Trans-)Jordan, and Iraq coming under British control, remained in place– at least until the British handed control of Palestine over to the United Nations in 1947…

So 109 years ago it was the imperial powers of Britain and France that got to divide up the Mashreq. Today, it seems that whole area of Syria and possibly also Lebanon is getting to be divided up between the two regional “great powers” of Türkiye and Israel. And this is happening with the blessing and possibly also encouragement of both the United States and Russia.

Just so we are clear about what is underway there…

Fallout from Putin’s backstabbing– for Gaza, and globally

What has united the Axis of Resistance for many years now has been the concept of resistance to Israel’s land-grabbing, aggrandizement, and frequent military assaults. The current Israeli government and, I would say, any government that’s foreseeable in Israel for many years to come, is quite set on continuing and expanding those behaviors. As we have seen, in spades, in Syria in two weeks since the fall of Asad. Hence, resistance to these behaviors will continue– and we have even seen some small signs of resistance within the newly Israeli-occupied parts of Southern Syria, itself.

Over the past 14 months, the Palestinians of Gaza have been subjected to the full force of Israel’s genocide machine; and they have continued to resist it even though at massive, almost unimaginable cost to their society.

From October 7 or 8 of 2023, the Palestinian resistance forces have also received significant support from Lebanon’s Hizbullah, whose repeated attacks against (mainly military) locations throughout mainly Northern Israel have kept a non-trivial portion of the Israeli military tied down in theaters other than Gaza. The resistance forces in Gaza have also received significant military support from Ansar Allah (the “Houthis”) in Yemen, whose actions have served to keep a portion of the Israeli air-defense system engaged and off-balance while imposing a real cost on those portions of global commerce that have sought to continue doing shipping business as usual with Israel. Other military resistance actions against Israel have come from Iran and from Iranian allies in Iraq.

Some but certainly not all of those military-solidarity activities will now be impossible because of the Israeli-US takeover of most of Syria’s strategic space on land and air. We might well conclude that all forms of political support to the anti-genocide resistance will therefore become much more needed.

It is in this domain of political action and political organizing that Putin’s back-stabbing of the Axis of Resistance may well have even more of an impact than in the military domain. Because if you consider, as I do, that Israel has been acting over recent decades (and certainly during the past 14 months) essentially as the “cast lead” tip of the spear of an otherwise-fading U.S. empire, then the fact that BRICS co-founder Russia has now in effect chosen to side with Israel rather than those who resist it, then that certainly has grave implications for a global society that has been actively working to break the hegemonic or near-hegemonic power that Washington has wielded over West Asia and most of the rest of the global system since 1990, and working to build a world built on human equality and human understanding rather than one built on “White” supremacy and hyper-militarized imperial dominance.

I do not have time here to explore all the challenges– and perhaps opportunities?– of the period ahead. Perhaps Israel’s military will find itself greatly over-extended in Syria and Lebanon? Perhaps Joe Biden will finally be able to produce a ceasefire agreement for Gaza that will salvage the lives of at least a portion of the Strip’s now starving people? Perhaps other forms of diplomacy are already underway that can salvage some portions of the struggle for truly multi-polar rather than US/Israeli-dominated world?

We can hope for all those things, and work actively to support many of them. And remember: in an era of such great flux and speedy transformations as the one we’re now living in, then big changes for the better are certainly also quite possible. The many ardently pro-Zionist pundits who are out there today crowing raucously about the collapse of the Axis of Resistance will not have the last say.