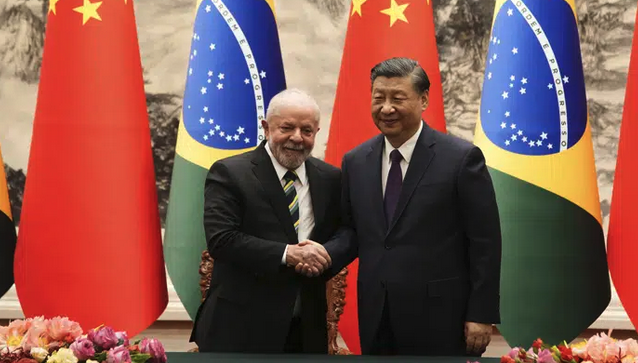

Globalities is currently releasing its new content in audio format. What follows is the text of the podcast episode I released April 14. Seen above: Brazil’s Pres. Lula Da Silva and China’s Pres. Xi Jinping, in Beijing yesterday. ~HC

Today is April 14, 2023. In today’s episode I’m going to, first of all, present a quick review of some of the key developments this past week has seen in international affairs and what some of them might mean. Then, I’m going to reflect a little on the longer-term historical significance of the seemingly rapid shifts we are currently seeing in the global balance…

But first: My survey of the major developments this balance has seen over the past week, and what they might mean more immediately:

Fallout from Macron’s recent visit to Beijing

Once again, as last week, this week’s major geopolitical developments have centered around the continuing diplomatic achievements of China’s increasingly sophisticated foreign-policy apparatus. Last week, one of the big events had been the visit of France’s President Emmanuel Macron to Beijing, and the warm, enthusiastic, and hospitable welcome he was given there, in both Beijing and Guangzhou.

Macron had traveled there with a group of French business leaders, including the head of the Airbus company. Those French business leaders signed a number of important deals with Chinese companies, including in fields involving advanced technology… And this, at a time when Washington is increasingly trying to isolate China’s high-tech companies from working with counterparts in the “West”!

After Macron completed his visit, there was a lot of worried commentary in the American corporate media about how his actions seemed to signal a break from Washington and Macron’s desire to return to the “strategic autonomy” that, historically, France’s President Charles De Gaulle had sought to pursue—that is, a french autonomy from the diktats of Washington.

I think we can look at Macron’s actions in a number of different ways. Yes, there was undoubtedly a return to a degree of ‘strategic autonomy’ from Washington. But what would you expect, after the Biden administration stabbed France and its ship-building industry so blatantly in the back in 2021, when they announced they’d persuaded Australia to back out of a longstanding deal to buy French submarines and instead to build much more expensive, and nuclear-powered, submarines under a deal with the United States and the UK, under something called the “AUKUS” agreement?

Secondly, in case no-one noticed this, Macron has been facing considerable unrest at home, over economic issues… a large proportion of which have been badly exacerbated by the diktats Washington has handed down about EU countries having to join the sanctions against Russia. So he and his economic advisors are doubtless very eager not to also have to break off their ties with the massive market and manufacturing hub that China has now become.

Rebuilding historic trade routes across Eurasia

Finally, on Franco-Chinese ties, I’d just note that the continued building of these ties, and of the economic links that China has with most other EU countries, are really a return to—or more accurately, an enhancement of—the kind of ties that countries at each end of the Eurasian landmass had back in the 13th century of the Common Era.

Many people in today’s Western countries tend to forget about those contacts—or indeed, the even earlier contacts that imperial Rome maintained for many decades with trading partners in India and China. Most of our education systems here in the “West” seem to assume that the world’s economic history simply started with the European “Enlightenment” and the era of the building of worldwide, very extractive, empires by some Western polities that accompanied that.

But no. Long before the West rose to the pinnacle of world power—clambering over the bodies of millions of dead Indigenous people worldwide, and of others seized, enslaved, and shipped to distant enslavement camps as they did so… Long before that all happened, the manufacturing hubs of China, India, and much of the rest of Asia were abuzz with innovation, in the spheres of both technology and economic management. The first time the adventurous Portuguese navigator Vasco Da Gama sailed around the southern tip of Africa and arrived in a port in India, he showed the local ruler the best gifts he had to offer him… and the wealthy Samudri of Calicut and his retinue laughed in amazement and derision at how primitive and paltry the gifts were.

And the learned people of the ports of India and China of that time also probably retained considerable knowledge of the ties their cities had long had with Western nations not via the sea route going around Southern Africa, but via the Silk Road… which was never a single overland route but a series of trade routes that crisscrossed both the lands of Asia north of the Himalayas and the always-busy sea-lanes of the Indian Ocean and the South China Sea.

Back in the 13th and early 14th centuries of the Common Era, 200 years before Vasco Da Gama sailed to India, the overland trails of the Silk Road were especially secure and well-traversed, as the governance of the area was united under something called the Pax Mongolica. That was what allowed Marco Polo and his uncles, and other traders, to travel safely as far as Shangdu, China. It might have taken them eight months or so to cross Asia by ox-cart from the Persian port of Hormuz. But they did so quite safely– and also, apparently, pretty profitably.

So now, since the launching of the Belt and Road Initiative by the Chinese government back in 2013, it is clear that Beijing is deeply committed to rebuilding robust ties, by land and sea, with the rest of the Eurasian continent, and also with countries all round the Indian Ocean and the South China Sea. In case you’re tempted, a train trip across the 4,100 miles from Beijing to London can now be done in just under one week.

The origins of ‘Atlanticism’

I have lived most of my life in a trans-Atlantic, Anglophone environment in which the dominant surrounding culture has always conveyed a very specific way of viewing human history. This culture always placed great emphasis on the role that the European “Enlightenment” played in initiating an era of unprecedented human progress… Only in small corners of the culture was there ever any recognition that the era of European “Enlightenment” actually inflicted great and lasting damage on the peoples of the Global South… the peoples, that is, of what the global-equality activist and thinker Vijay Prashad calls, “The Darker Nations”.

In the post-World War-Two England in which I grew up, many people had a deep fascination with “America”. It was the United States that had “saved” England in World War Two. It was America that, in the 1950s, was taking over the leadership of what was described as “the civilized world” from what was by then an evidently failing and fading British Empire. When I was a child, our comfortably middle-class English family would eagerly await the boxes of outgrown clothes that a kind family in “America” would periodically send to us. My eldest sister was thrilled to receive a scholarship to an elite American boarding school for her final year of secondary education and we all eagerly awaited the news she would bring us of the latest advances in American culture when she returned to our family in 1961. Clearly, for us, back then, trans-Atlantic ties were the pinnacle of a stable world system…

Now, six decades later, many leaders of the national security policymaking apparatus here in the United States—a country to which I immigrated in the 1980s—clearly think that that is still the case. For them, the security of the world is all about the internal cohesion and the world dominance of NATO, the North Atlantic Treaty Alliance. To preserve the internal cohesion and strength of NATO, the decisionmakers in Washington have poured many tens of billions of dollars’ worth of military and non-military aid since February 2022. They showed themselves ready to “enforce” the internal unity of NATO by blowing up the Nord Stream pipelines that provided vital energy inputs for Germany’s industries and communities… and also to impose significant other economic hardships on most other European countries through their insistence that Europe join the punishingly broad sanctions against Russia.

And lest we forget: To underscore their desire that Washington, through NATO, be able to continue to dominate the European battle-space, the Biden administration has very actively discouraged, deterred, or undercut, all the initiatives that other powers—whether, China, Brazil, the Vatican, poor old President Macron, or others—have launched, to try to achieve a speedy negotiated ceasefire in Ukraine.

Viewed from inside the Washington bubble, this might make some sense? Viewed from anywhere outside that bubble, it is madness! And a very destructive form of madness, too: one that has led to the conflict in Ukraine just continuing to grind up lives, communities, prospects, and resources both within and far from that conflict-ravaged country.

For anyone whose main source of news and information is the Western corporate media, it is seen as supremely important that “the West” achieve a demonstrable “victory” in Ukraine, or perhaps more accurately, that it inflict a demonstrable “defeat” there on Russia’s President Vladimir Putin. President Biden and his acolytes continually cast the conflict in Ukraine as a contest between “democracy” and “authoritarianism”… and one whose outcome has truly global implications and impact.

But the leaders of two of the largest democracies in the world—those in India, population 1.4 billion, and Brazil, population 213 million—see the situation differently.

Both these governments, along with that of democratic South Africa, now strongly favor working for a speedy ceasefire in Ukraine, over the continuation of the conflict there.

Pres. Lula’s visit to Beijing, and the emerging bloc of the Global South

Another significant news item from this week has been the state visit that Brazil’s President Lula Da Silva has made to Beijing, and the swearing in there of his longtime political ally Dilma Roussef as head of the Beijing-based New Development Bank, the global lender that is China’s answer to the Washington-based “World Bank” and International Monetary Fund. Brazil has also recently agreed with China to price all the bilateral trade between them in yuan, thus significantly reducing both countries’ dependence on the dollar.

The conflict in Ukraine does, certainly, continue to inflict non-trivial damage on the countries of the Global South. Its does so through its effects on the prices of grain, fertilizer, and other commodities whose international shipment has been disrupted by the conflict. It does so by diverting international attention and resources from the urgently needed campaign to contain carbon emissions and combat global warming—a process that has already started to impact many communities worldwide but that threatens by far the greatest amount of destruction in the countries of the Global South. And it does so by bringing all the peoples of the world uncomfortably close the risk of total nuclear extinction.

Those are the main reasons why so many leaders and thinkers in the Global South are eager to see the conflict in Ukraine brought to a speedy and negotiated end. They don’t see the need to pull for the “victory” of one side or the other. If the conflict can be speedily ended through negotiations, they say, please make it happen, and soon. And some, like President Lula or China’s President Xi, have offered to be part of a mediation team that can broker this peace effort.

But in the mean-time, though the countries of the Global South want to see the conflict end, they are not sitting around to wait for that to happen. These days, while the people in the NATO bubble are deeply pre-occupied with the situation in Ukraine, leaders in the Global South are busy pushing forward their plans for new trade deals, for new trade pathways, for successful economic development, and for building the physical and financial infrastructure that’s needed to make all this happen.

From their perspective, the conflict in Ukraine looks less like the global make-or-break contest between good and evil that is portrayed in Western imaginary… and more like a limited regional struggle between two groups of “White” nations, over there on the distant shores of the Black Sea, that has only a limited capacity to interrupt their own large-scale projects for continued infrastructural and economic development.

It is a different way of looking at things, and one that is not totally focused on the war in Ukraine… or on topics associated with that, like the latest trove of high-level secret documents that has apparently been leaked by a young techie member of the U.S. military over recent months.

This week’s big developments in West Asia

There have been three developments of note in West Asia over the past week. The rapprochement between Iran and Saudi Arabia that was recently brokered by China’s foreign minister has already started to show some encouraging results in Yemen, an impoverished, mountainous country where those two regional powers have, along with the United Arab Emirates, been engaged in a brutal civil war that has killed hundreds of thousands of people over the past eight years.

Just today, the International Committee of the Red Cross has overseen the release of 300 prisoners-of-war by the (Iranian-backed) Houthi administration in the north Yemeni city of Sana’a, with the ICRC flying the released men to the south Yemeni city of Aden, where the rival Saudi-backed faction is headquartered. The ICRC spokesperson said that two more reciprocating prisoner flights are scheduled to happen over the next two days. This is real progress, and much more is planned.

The rapprochement that China brokered between Saudi Arabia and Iran has wide consequences throughout the whole of West Asia (the area formerly known by a Eurocentric monicker: the Middle East.) One of the other effects of this rapprochement is that it’s been easing the resumption of relations between the government of Syria, which is allied with Iran, with all those other Arab countries that until recently were working very actively to topple Syria’s president Bashar al-Asad. So one of this week’s other notable developments in West Asia has been the welcome that Saud Arabia’s rulers gave this week to Syrian Foreign Minister Faisal Mekdad, who held talks with his Saudi counterpart there on Wednesday.

And today, in a follow-up to that visit, the Saudis have been hosting envoys from Egypt, Jordan, and other Arab countries to formulate a plan to bring Syria back into the Arab League, the regional body from which it was suspended in 2011 and expelled in 2013.

I should note that in both these cases—that of the rapprochement in Yemen and that of Syria’s reintegration into the Arab League—the bold Chinese achievement in brokering last month’s reconciliation between Iran and Saudi Arabia did not occur in a regional vacuum, but it has also been backed up by, and strengthened by, other moves undertaken by various governments within West Asia to push for de-escalation and a reduction of tensions between Iran and Saudi Arabia…

This has been quite counter to the main thrust of US and Israeli diplomacy in the region, which has been mainly focused on keeping the tensions with the Islamic Republic of Iran and its allies and friends in the region constantly at a fever pitch. As we know, the United States and Israel have both been working hard for many decades to bring about regime change in Iran and Syria, and they have used a variety of mechanisms to try to bring this about. The United States has maintained crippling sanctions on both countries for many years. It has openly supported, funded, and armed the various opposition groups in Syria; and it has given considerable, slightly more discreet aid to opposition groups in Iran. Israel has used deadly sabotage raids against Iran and has mounted repeated air-raids against targets deep inside Syria over the course of many years now.

Inside Syria, too, Israel and the United States—and also Turkey—all have significant ground forces that have occupied large chunks of land inside Syria for a number of years, in open violation of international law. Israel, for its part, has occupied the fertile Golan area of Syria ever since 1967, and it annexed it in 1981. No other country recognized that annexation as valid until 2019, when President Donald Trump decided to do so. And significantly, President Biden has never rescinded his recognition.

This fact of Israel’s continuing, illegal occupation of Golan—along with the very evident failure of Syria’s many well-armed opposition groups to win enough domestic support to topple Pres. Asad’s government— is all part of the background that helps explain why so many other Arab governments have now decided to make their peace with Asad…

So now, here’s the third of the globally relevant developments the West Asian region has seen in the past week: That is, the Pentagon’s unprecedented decision to send a nuclear-powered guided-missile submarine from the Mediterranean, where it is part of the European theater, through the Suze Canal and down around the Arabian Peninsula toward the Persian Gulf. The USS Florida, which is capable of carrying up to 154 Tomahawk cruise missiles, transited the Suez Canal last week and is probably right now near the strategic Iranian port of Hormuz.

So this seems to be the only counter the Biden administration can think of using, to answer the recent flurry of successful Chinese and intra-regional diplomatic activity in West Asia?

The 500-year perspective

And finally, this:

What you see when you look at any particular period in world history depends to a large extent on where you’re standing, or perhaps more precisely what your starting-point is. If you live in the kind of atmosphere that is drenched in West-European Enlightenment thinking, then you’d probably conclude that the last 500 years of world history have been period of almost unqualified “progress”, in most realms of human endeavor, whether in terms of economic development, technological prowess, scientific discovery, communications, social equality, or democratic governance. Oh sure, there were some black marks or setbacks along the way, like the unfortunate history of chattel slavery, or colonial aggrandizement and extractions, or the European powers’ numerous wars against non-Europeans or each other… But all in all, this thinking goes, the past 500 years have been a period of “progress”, nearly all of it spearheaded by Westerners who bravely overcame all the forces described as forces of darkness.

Atlanticism, which is the marrying of the destinies of the Anglo-origined, colonial entities of the United States and Canada to that of the West European heartland, is in many ways the current pinnacle of this historical process… and now it has been augmented in the “Five Eyes” arrangement, or in AUKUS, by the strengths and destinies of the two Anglo-origined colonial entities in the South Pacific.

Of course, to many people of African heritage, the concept of “Atlanticism” has a much more ominous tone to it. I hope to investigate the whole outrageous history of trans-Atlantic slavery quite a bit more as the Globalities project proceeds.

These past few weeks, though, I’ve been thinking a lot about the world that existed before the era of European hegemony. To a large extent it was a Eurasia-centered or Eurasia-plus Indian Ocean-centered world…

Of course, in the landmasses of the Americas, and the archipelagos of the Caribbean and the South Pacific, before those regions suffered the violence of “contact” with—and conquest by—the Europeans, they were home to numerous other civilizations, that had many stunning technological and social achievements of their own. And there were even vast, well-connected land empires in North and South America in that pre-Columbus era. But in the Eurasian heartland and around the rim of the Indian Ocean, the degree of connectedness among the region’s many different civilizations was distinctive and extraordinary.

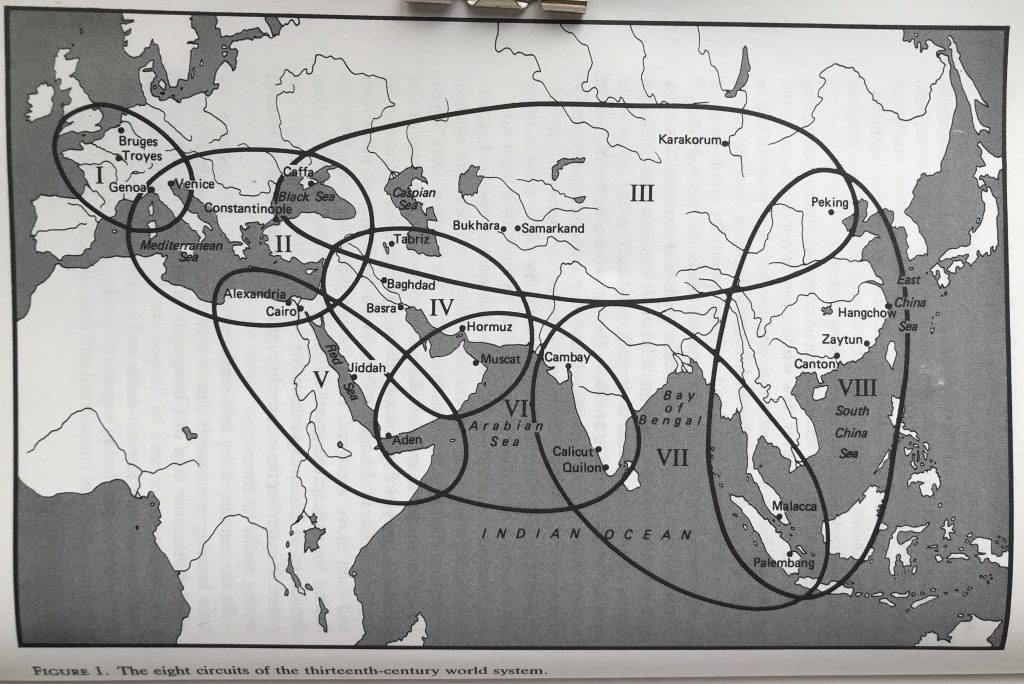

I have recently been reading Janet Abu-Lughod’s brilliant book, Before European Hegemony: The World System AD 1250-1350. She admitted up-front that her purview excluded any mention of the situation of the Americas in that era. Her book was published in 1989, and doubtless other scholars have pushed the kind of research that she was doing even further in the 30 years since then. But in her study, Dr. Abu-Lughod used the innovative approach of identifying eight distinct trading sub-systems in the Eurasian / Indian Ocean region in that era. (Here, specially for this print version, I can reproduce that:)

One of those was the great Mongol-dominated land route of the traditional “Silk Road”, wending its ways through fabled cities like Samarkand and Bukhara. One was a basically territorial route across the body of today’s France. But the other six sub-systems were all maritime routes, each of them stitching across a significant body or bodies of water, running from the Mediterranean right across to the South China Sea and the East China Sea.

I have to say I wish Dr. Abu-Lughod had paid more attention to the coastal networks down Africa’s eastern coast. But still, her approach and the serious attempt she made to consult local sources for each of her sub-systems, make the book distinctive and deeply informative.

It was into this “system of trading systems” that, in the middle of the 14th century, the Black Death intruded, apparently traveling west along these trade routes from China to Europe. That was one big upset… As had been, a little bit earlier, the breakup of the Mongols’ massive land empire into, essentially, four constituent parts, each of them ruled by a Mongol descendant, but many of whom came to adopt the religion and culture of the peoples among whom they lived.

Regarding the maritime trade systems in and around the Indian Ocean, the final intrusion into these previously existing systems was the arrival in this ocean in 1498 of the Portuguese adventurer Vasco Da Gama. The wealthy trading ports around the Indian Ocean had never experienced anything like the level of violence that he and the other heavily-armed Portuguese plunderers who came after him brought to their region! You could say that their arrival and their activities in the region were as shocking and caused as much—if not more—havoc in the Indian Ocean as the Americans’ use of atomic weapons against East Asia in 1945…

And the English and Dutch plunderers who followed the Portuguese a century later just compounded the disruption and destruction of just about all the region’s once-great civilizations. By the 1850s, the whole of the “concert of Europe” had arrived in East Asia, and was even able to start subjecting the great country of China to its century of humiliation. And by that time, the United States was also part of the looting and subjugation of East Asia.

For me, therefore, seeing the resurrection of China’s role in world affairs is not a shocking thing. Indeed, seeing the smart way in which China’s leaders have been using diplomacy, trade, investment, and other economic ties to rebuild their country’s power I really welcome the fact that in today’s world, these kinds of instruments of “soft” power may well prove much more effective at building a decent world than all the militarism and hard, destructive power that nations of West-European origin have been using all around the world since the 1400s.

That’s why, these days, I am following the achievements of China’s diplomacy with great interest. One day very soon, let’s hope we can see China, Brazil, and the rest of the BRICS countries use their clout to bring about a ceasefire in Ukraine. But whether or not that happens, China’s diplomacy is already acting as a force for good in West Asia, and in several other parts of the world.

I always learn so much from you, and that was the case again with this latest podcast. Thank you. I appreciate your perspective which challenges the mainstream media’s drool. And you challenge me. Honestly, I have a difficult time staying focused as I listened to this episode because you seem to wander from history to current events and back to history. I understand the thread you’re trying to weave and my inability to follow it is more likely a reflection of my lack of education in these topics. So my question: who is the audience you’re reading/writing for? Let me suggest who I think you’re NOT reading/writing for —- the average American who has little time outside of his/her family to think about geopolitics; and perhaps the rising new generation of American leaders (20 and 30 something year olds) who get their information in shorter soundbites? Do you have a goal in mind beyond the deep satisfaction of learning yourself and sharing what you’ve learned?

Lora, thanks so much for this feedback, which is extremely helpful! I think you’re right that I packed ways too much into this dispatch– probably especially for people listening to the audio version. I go through periods, including when I had my eye problems last year, when I listen to a *lot* of podcasts, which generally I do only when I’m doing some otherwise-boring physical exercise or when I’m on a long drive.

So generally, I think podcast listeners are okay with 30- to 60-minute episodes. But probably the problem with mine is the density of the info that I’ve packed in there, and maybe also the zipping around between historical periods that you mentioned….

This might be alleviated if we had the episodes be more like a conversation? Why don’t we talk about you coming into the project to be, say, my conversation-partner or interrogator?