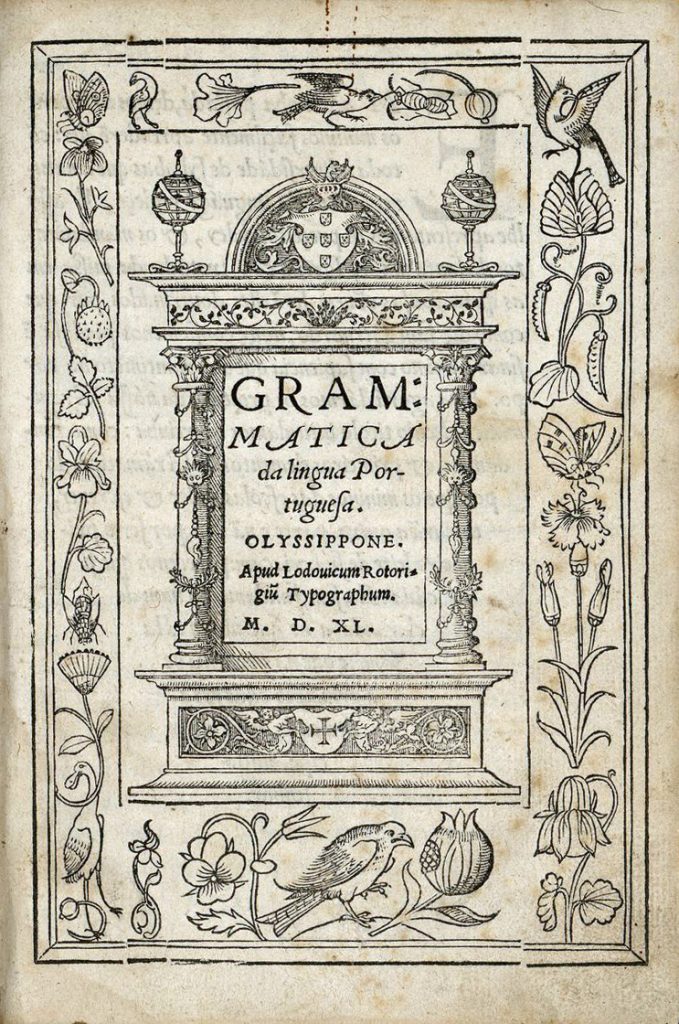

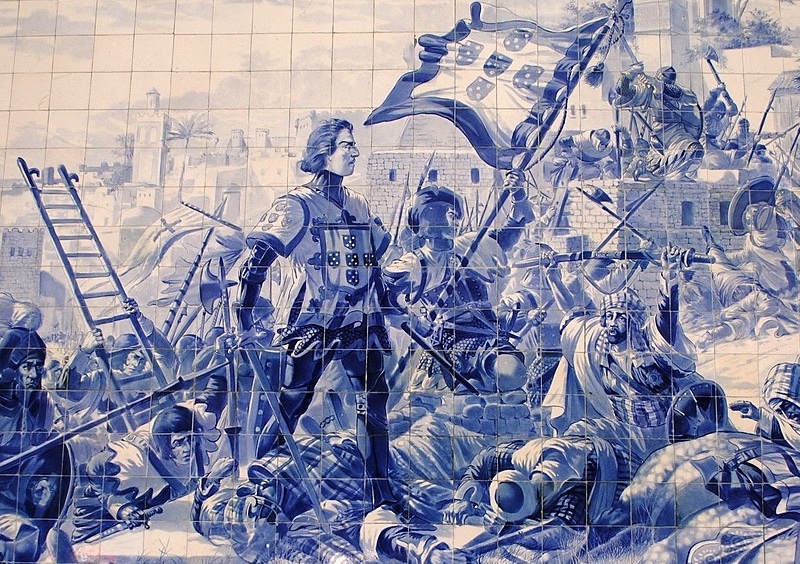

The above image is a tilework rendering of Portugal’s Prince Henry (“the Navigator”) conquering Ceuta in North Africa in 1415 CE

Broad phalanxes of commentators, politicians, and pundits in the United States, Europe, and elsewhere speak easily about the role of “the West” in world affairs; and the contest/contrast between “the West vs. the rest” has even become a thing.

But what is this “West”? What do people mean when they use the term?

At a time when the effective hegemony that the United States and its allies in “the West” have exercised over the peoples and politics of the world is starting to crumble, it seems worth exploring the historical record of “the West” a little more systematically.

Is “the West” only a vestige of the West-vs.-East bipolarity of the Cold War? Or, is it a civilizational matter, as in the habit of many U.S. universities to offer courses in “Western Civ” that draw a straight line back from Peoria to the civilizations of Greece and Rome? Or, is “the West” best defined in contrast to an “Orient” that has all the—deeply “Orientalized”—attributes of despotism, backwardness, and so on that have been ascribed to it? (And is “the West” thus largely co-terminous with modernism itself?)

I’ve been thinking on, and writing about, this issue for a number of years (including here), and now I’m planning to present my best current understanding on the history of “the West” as we see it today, summarized into six historical episodes. Today, I present Episode 1.

(I realize I’ve left a lot out of the summary and would much welcome helpful suggestions for improvement, which can be left in the comments.)

Episode 1: Five European trans-oceanic plunder projects

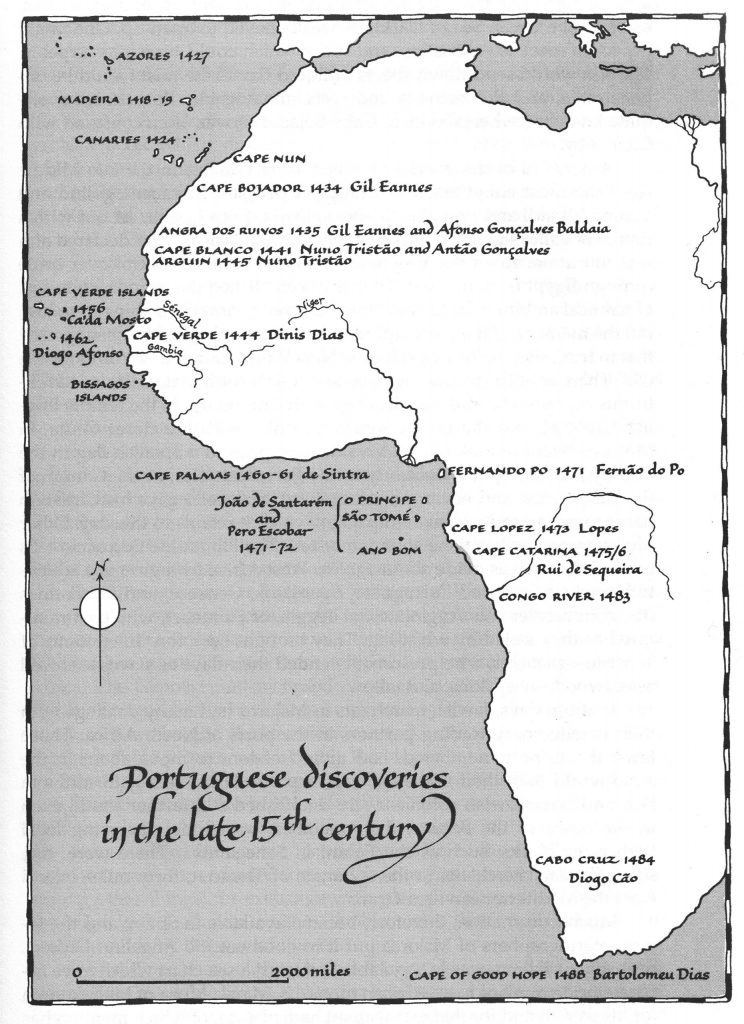

Starting in 1415 CE, the leaders of five entities perched on the West (Atlantic) coast of Europe followed each other, largely competitively, into the pursuit of long-distance projects of colonial plunder on continents and land-masses far from their own. These were, in chronological order, the monarchs of Portugal (1415), Spain (1492), and England (1577); the more republican/corporatist leaders of the Netherlands (1602); and the king of France, in 1635.

These trans-oceanic projects required strong skills in all matters maritime and military. Portugal and Spain had developed those skills through the centuries-long campaigns they fought to win control of Iberia from the Muslim lords who had held it since the 8th century. England and Netherlands were Protestant powers. They had gained their martial and maritime skills by battling the strongly Catholic kings of Spain. France, which was located between the Protestant and Catholic powers, gained the needed skills by battling, on occasion, all of them.

These often-vicious contests and conflicts among the “Plundering Five” were carried by them into most of the areas of the Americas, Asia, and Africa where they were doing their plundering. There was little sign of a unified “West” in those early centuries! On a few occasions, however, the local commanders of different plundering polities would cooperate with each other to confront a particularly robust challenge from Indigenous resisters.

The rulers back home in the respective metropoles did not, of course, run their plunder projects themselves. Instead, each of them built a large administrative structure to do so. In the case of Portugal and Spain, those structures were organs of the monarchical state, as was the one that the French king later built. In Netherlands and England, by contrast, the rulers contracted out most of the administration of the plunder projects to other wealthy individuals who pooled their resources (and risks) through the new invention of “chartered companies.”

The success (= hyper-profitability) of those European plunder projects of the 15th through 17th centuries thus spurred the development of crucial modern-style proto-capitalist financial institutions.

These projects also spurred the emergence and consolidation of the home polities’ various “national languages.” At one level, it might seem quite mysterious why Portuguese would have developed as a language distinct from (Castilian) Spanish. Or Dutch from German (Deutsch). But in each case, the need for effective—and to some extent confidential—communication among commanders and participants in the separate plunder projects fostered the emergence in each of a single, somewhat distinct, language of “empire” and of the standardized orthography that was required to communicate it over long distances.

(See my earlier essay on the role of empire in “fixing” the national languages of the metropoles, here. I definitely critiqued Benedict Anderson there!)

Hence, we could see each of those five parallel trans-oceanic plunder projects setting the scene for, and providing the finances for, the development back home in the metropole of the essential components of what today we recognize as a modern-era nation state: a distinct “national” language and the culture that arose around it; and the administrative and financial institutions required to run a “national” economy. These attributes would all (later) prove essential to the rise in the metropoles of manufacturing capitalism itself. In this respect, I conclude that global imperialism was not, as Lenin argued, “the highest stage of capitalism” but rather, a precursor to the emergence of capitalism in Western Europe.

Two final footnotes here:

First: I wrote above that the five West-European plunder projects were all pursued separately and often in competition with each other. That was true except during the period 1580-1640. In 1580, for obscure dynastic reasons (and after a notable Portuguese military fiasco in North Africa) the Spanish monarch came to rule also over Portugal.

During those years of the “Iberian Union”, Madrid neglected many of the functions essential to maintaining the (older, and very far-flung) Portuguese empire. That provided the chance—in East Asia, India, Brazil, and elsewhere—for the feistily agile and always brutal Protestant navies to swoop in and capture many of Portugal’s former positions. In 1640, the lords in Portugal rebelled against Spain and reasserted their own monarchy and sovereignty. But by then the global empire they had been building since 1415 was much reduced. (In Brazil, they were able to claw back control of the positions the Dutch had briefly held there.)

Second: The consolidation of the administrative/financial backbones of the plunder projects was one factor that differentiated the maritime plunder projects that started in the early 15th century CE from the earlier, less durable project pursued by another power based on Europe’s West coast: the Vikings.

Another difference lay in the fact that a large part of the Vikings’ project had been conducted in the Mediterranean and Black Sea. The later projects of the Big Five were, by contrast, focused primarily westward and southward along the Atlantic’s shores and then from there into the Indian and Pacific Oceans. These much lengthier maritime routes required much more highly centralized administration by the authorities back home in the metropole than the Viking raiding and trading of centuries past had ever needed.

I wish you had started from the Renaissance since Europe was consumed by its own folly in the dark ages. I also look forward to future segments that can draw on the insight I found in Marx’s Grundrisse, re differential impact of colonial conquests on Spain/Portugal versus England/Holland.

Mohammad, thanks for this. As I proceed with the project, please add in any insights from the Grundrisse (or elsewhere) that you think helpfully expand the narrative!

I still have some strong impressions from history classes in US public schools. The European explorers who sailed to other continents and discovered new people made one of these impressions. They seemed big, bold, brave, and part of the natural order of things. This description is accurate in part.

But the more complete description in the main post brings one to pause. Summarizing in blunt terms, the Europeans were predators in part, and far-flung indigenous people were their prey. There is a legacy from this that has continued to our time.

Predation accepted, there is no reason to accuse Europeans of some genetic quirk. Some of the Chinese, East Asians, Africans, and Native Americans (North and South) who preyed on each other, might well have preyed on Europeans given motive and opportunity.

Anyway, there is a point to be made regarding recent changes in the world’s economic and political structure. The Russians, Chinese and others in a forming coalition, seem to reject any further role as prey. They seek equality of treatment, or so the Russians and Chinese have jointly declared in statements that have not been covered in the Western news. Former colonial countries and most of the English-speaking countries must face the new coalition and need a harmonizing revelation of their own if they are to continue in good form.

FWH: The glorification of the role that West European navigators played in “discovering” the other continents of the world is certainly a strong part of the historical canon of Western nations– especially of the United States and other polities that are the settler-colonial progeny of those “discoverers.” It’s good to find alternative views, such as that in this book, “Pirate Nation”, that retired British Royal Navy officer David Childs wrote about “Sir” Francis Drake and the other adventurers, swashbucklers, and pirates who founded Britain’s maritime empire. (Personally, unlike many people, I’m not a fan of pirates.)

As for genetics: No! I make absolutely no claim that such predation was in the genes of those West European communities. They had the fighting & navigating skills; they had the opportunity; they had the motivation, and they went for it. Interestingly, in the same seminal 15th century the Chinese Empire, which had sent the talented admiral Zheng He out on seven amazing voyages aimed at, basically, economic diplomacy, not conquest, that had taken his absolutely super-sized fleet all around the Indian Ocean… just closed the whole project down. Not, I imagine for any “genetic” or “moral” reasons; but they needed to focus the empire’s attentions and investments elsewhere..

very good