The photo shows a unanimous vote at the U.N. Security Council in January 2022, affirming that nuclear wars must never be fought

Unless your name is Tom Friedman, I guess you’d agree that the world is not flat. But what shape does our world have today—and what shape of a world do we want to build over the years ahead?

I’m pulling strongly for the kind of multipolar order in which all the world’s children have a decent chance of growing up in an environment with a sustainably livable climate and from which the threat of nuclear ecocide has been removed.

Joe Biden seems to have a different preference. Time after time, and in a rising crescendo this past week, he has loudly been painting the world as dominated by a bipolar fight between what he calls the “rules-based order” and Russian aggression—and one that the “West” (as embodied by NATO) must win… And from the other side of the Ukraine frontline, Russia’s president Vladimir Putin has been loudly proclaiming his own, mirror-image version of that view.

There are two big problems with seeing the world as essentially bipolar:

- The zero-sum-game aspect of any bipolar view of the world entrenches competitive actions at a time when the already evident effects of climate change (hello!) and the threat of nuclear annihilation demand cooperation, rather than competition.

- Our world is already deeply and irreversibly multipolar! Hence, seeing it as bipolar, or acting as if it were, is extremely retrograde and ends up being damaging for all the peoples of the world (and almost certainly counter-productive for any leader who follows such a path.)

We should all be glad that this week, the government of China has published a concept paper for a new “Global Security Initiative” (GSI) that presents a realistic, essentially multipolar description of the nature of global power. And just today, Pres. Xi Jinping has issued a powerful call for a ceasefire and peace talks in Ukraine that is clearly derived from the GSI’s principles.

There’s no word yet on whether anyone in China’s corps of global diplomats has been exploring with Moscow or Washington whether and how a Ukraine ceasefire can be attained, or what role Beijing or others might play in that diplomacy. (If such contacts are being conducted, by any party, we most likely wouldn’t hear about them until they were close to success… For my part, I live in hope.)

Meanwhile, two studies recently published in “the West” underline the degree to which power in the world has already become widely diffused. In this one, “The New Geopolitics”, Columbia University economist Jeffrey Sachs focuses on the economic underpinnings of today’s world. And in this one, “United West, divided from the rest”, three analysts from the European Council on Foreign Relations look at the degree to which the public attitudes in China, India, Türkiye, and Russia already diverge starkly from those in NATO countries.

In today’s essay, I will quickly summarize the key findings of the Sachs and ECFR papers, then offer my own preliminary thoughts on the nature and shape of power in today’s world.

Key points from Sachs

Sachs bases his argument on the economic fundamentals. He notes that

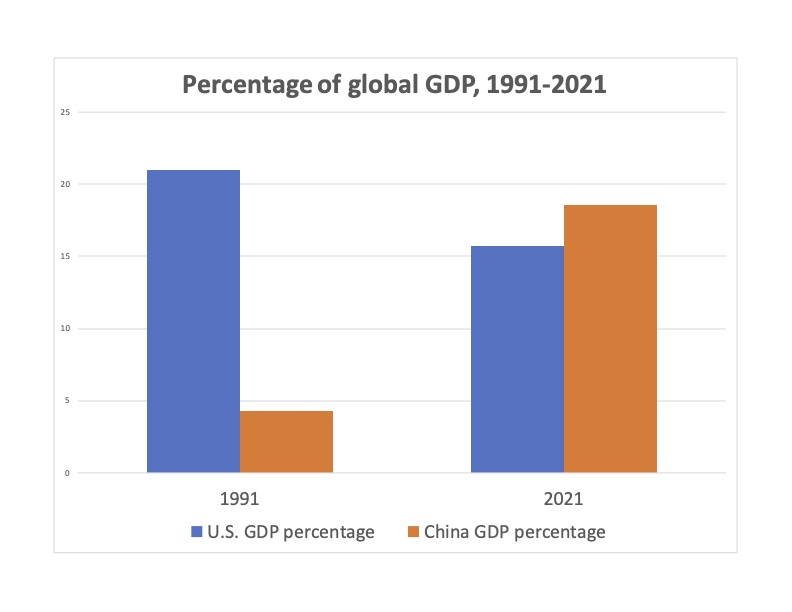

Between 1991 and 2021, China’s GDP (measured in constant international dollars) grew 14.1 times, while the American GDP grew 2.1 times. By 2021, according to IMF estimates, China’s GDP in constant 2017 international prices, was 18 percent larger than U.S. GDP. China’s GDP per capita rose from 3.8 percent of the U.S. in 1991 to 27.8 percent in 2021…

… Nor should we neglect the rising economic power of both India and Africa, the latter including the 54 countries of the African Union. India’s GDP grew 6.3 times between 1991 and 2021, rising from 14.6 percent of America’s GDP to 44.3 percent (all measured in international dollars). Africa’s GDP grew significantly during the same period, eventually reaching 13.5 percent of U.S. GDP in 2022… Africa is also integrating politically and economically, with important steps in policy and physical infrastructure to create an interconnected single market in Africa.

Here’s a little graph I made to illustrate another of Sachs’s key data-points:

And here’s a map I grabbed from somewhere else (presumably, somewhere German?) that illustrates the degree to which, between 2000 and 2020, China’s trade with the countries of the Global South and Europe came to eclipse that of the once-mighty United States…

Here’s another set of powerful data-points from Sachs:

the BRICS, constituting Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa, have also overtaken the G7 countries in total output… In terms of combined population, the BRICS, with a 2021 population of 3.2 billion, is 4.2 times the combined population of the G7 countries, at 770 million. In short, the world economy is no longer American-dominated or Western-led.

The whole of Sachs’s paper is worth reading. He offers intriguing critiques of the four major geopolitical theories he sees as prevailing in Western thought. The major problem with all of them, he writes, is “they view geopolitics almost entirely as a game of winning and losing among the major powers, rather than as the opportunity to pool resources to face global-scale crises.”

Contra those theories, he argues for a robustly multilateralist approach:

[T]wenty-first-century multilateralism should build on two foundational documents, the UN Charter and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and on the family of UN institutions. Global public goods should be financed by a major expansion of the multilateral development banks (including the World Bank and the regional development banks) and the IMF… It should bring the new cutting-edge technologies, including digital connectivity and artificial intelligence, under the ambit of international law and global governance. It should reinforce, implement, and build on the vital agreements on arms control and denuclearization. Finally, it should draw strength from the ancient wisdom of the great religious and philosophical traditions. There is a lot of work ahead to build the new multilateralism, yet the future itself is at stake.

The case Sachs makes seems even more compelling in light of the year-long conflict in Ukraine that has already inflicted major damage on Ukrainians and other peoples around the world and brought us closer to a nuclear confrontation than any conflict since the Cuban crisis of 1962. I could, and do, question a couple of the points he made there. (For example, regarding the financing of global public goods, why does he mention only the U.S./NATO-dominated Bretton Woods institutions while making no mention of the increasingly capable BRICS-led financial institutions?) But his stress on the fact that, “The world economy is no longer American-dominated or Western-led” is an important one for citizens of Western countries to take to heart.

So too—especially for those of us committed at a fundamental level to the equal worth of every human person—is the reminder he provides about the demographic weight of the Global South. Sachs places the combined population of the G7 countries at 770 million. I recently ballparked the combined population of all the European and White settler-colonial countries in the world at around 11 percent of the world’s total population of 8 billion.

Just fyi, 11% was also the proportion of the population of South Africa that was classified as “White” during the latter days of Apartheid…

Key points from ECFR’s study

Pres. Biden and most other NATO leaders often speak as if their decision to confront Russia somehow represents the will of the large majority of humankind. It does not. And when he or news reports in the Western corporate media refer to “a large majority” of the world’s countries supporting, say, a UN General Assembly resolution calling for a Russian withdrawal from Ukraine, they nearly always fail to mention that the countries that abstained from that vote, or voted against it, represent well over half of humanity. It is only rarely that a Western leader acknowledges, as France’s Emmanuel Macron recently did, that NATO’s arguments for confronting Russia have not proven persuasive in most of the rest of the world.

And equally rare that a major organ of the corporate media would actually mention this phenomenon. So hats off to the Washington Post for running this piece of solid reporting on this matter today, by Liz Sly!

Macron, Sly, and the WaPo aside, the solipsistic disregard with which most of the Western political elite considers the views of the world’s global majority regarding Ukraine recalls the (possibly apocryphal) headline said to have appeared in a long-ago London newspaper: “Fog in the Channel, Continent Cut Off”…

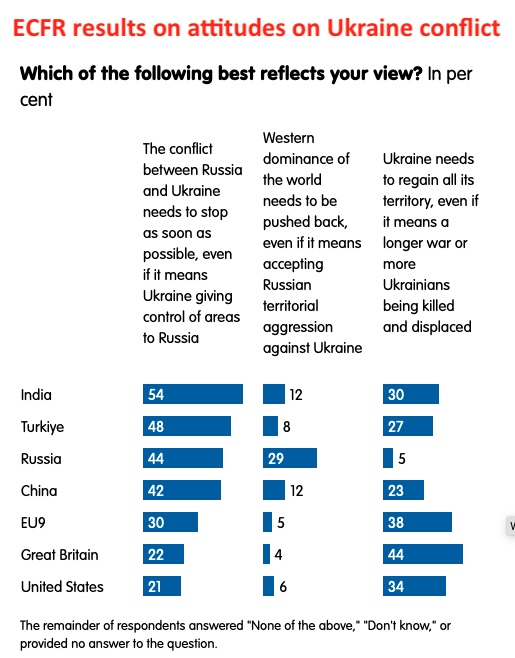

Into this stew of Western disregard of the attitudes of global humanity toward the Ukraine conflict now bravely steps the European Council on Foreign Relations. Their new study presents the results of opinion surveys they had commissioned in December and January in nine EU countries, in the UK, the United States, China, India, Türkiye, and Russia. While we should all recognize the inherent problems of all opinion surveys and the very incomplete scope of this study’s purview, their results are nonetheless fascinating.

The authors summarize their main findings as follows:

- Russia’s war on Ukraine has consolidated ‘the West;’ European and American citizens hold many views in common about major global questions.

- Europeans and Americans agree they should help Ukraine to win, that Russia is their avowed adversary, and that the coming global order will most likely be defined by two blocs led respectively by the US and China.

- In contrast, citizens in China, India, and Turkiye prefer a quick end to the war even if Ukraine has to concede territory.

- People in these non-Western countries, and in Russia, also consider the emergence of a multipolar world order to be more probable than a bipolar arrangement.

Their report contains numerous very informative graphs. This is the key one, on Ukraine:

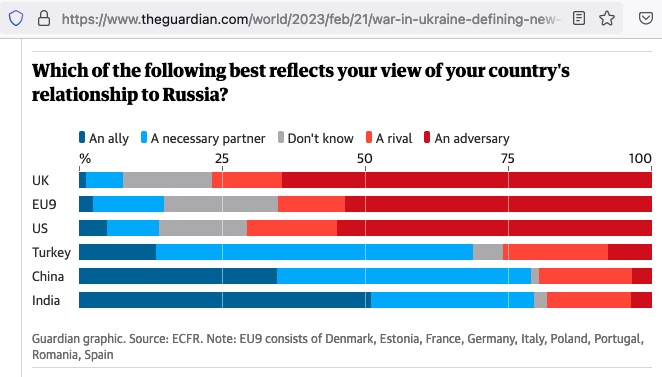

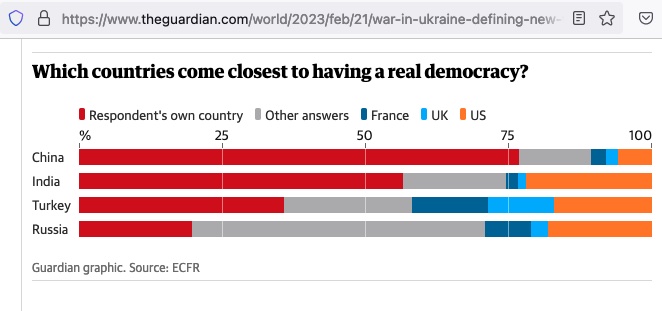

From London, the Guardian has also presented a summary of the ECFR’s findings. On that matter of views of the Ukraine conflict, the Guardian‘s graphic was very misleading: they left out the numbers from the ECFR’s—very significant—second and third columns! The Guardian‘s other graphics do a better job of representing the ECFR’s findings and are more visually compact than ECFR’s graphics.

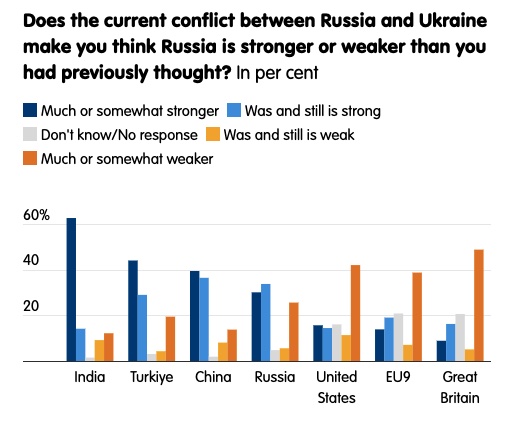

Here’s the Guardian graphic on attitudes toward Russia:

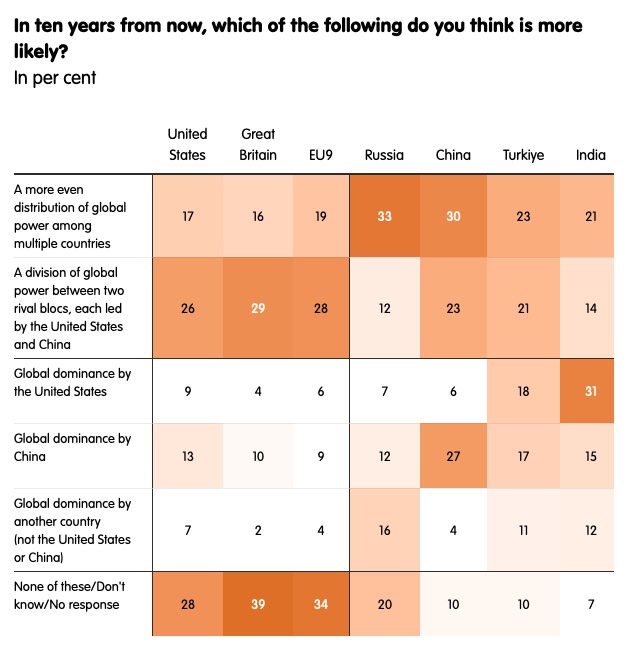

And this one is interesting and significant:

The ECFR study presents much more information than was in the Guardian‘s coverage. Here’s an ECFR finding showing that few of their respondents from the Global South have been buying the torrents of Western propaganda to the effect that the Ukraine war has “revealed Russia as weak”:

That is quite a stark West-vs-Rest divide! (The findings from Russia seem interesting, here as elsewhere in the study. I do wonder whether any survey conducted by a West European body within a currently “hostile entity” can be judged as coming even close to being reliable?)

And here, to bring my quick summary of the ECFR’s findings handily back to the main topic of this essay, is another of their key graphics:

I am intrigued by two of those findings in particular: that only 9% of Americans expect the U.S. to be globally dominant in 2033… and that 31% of Indians expect it to be!

Just one final note on that graphic—or indeed, on any of the graphics in this section. We need to keep in mind that, inasmuch as the stated numbers can be considered “representative” of the views held by people in the listed country or grouping, still, the sheer disparity in population size between those entities is massive. Hence, in the above block-graph, Great Britain (population 68 million) is given equal width to the United States (331 million) and—even more bizarrely—noticeably greater width than China (1,439 mn), India (1,380 mn) or the EU (447 mn).

Some concluding thoughts

Ever since I wrote a little book back in 2008 titled (a little embarrassingly to me, today) Re-engage! America and the World After Bush, I’ve been fascinated by the relationship between the United States and the rest of a global community that American leaders also claimed to lead. In that book, I was exploring the disconnect between, on the one hand, the claims that America was a champion of democracy and should lead the world and, on the other, the reality that Washington’s domination of global military and economic affairs allowed it to ride roughshod over the interests and claims of that vast majority of humankind that is not American.

I am still fascinated by that disconnect. The intervening 15 years have taken us through the presidencies of Obama and Trump and now the first two years of the Biden presidency. But shockingly little has changed in these years in the way the vast majority of members of the U.S. elite talk about America’s role in the world. American “leadership” and the global fight between “democracy” and “authoritarianism” are still the watchwords of most of these people. And meantime, apparently unrecognized by them, the degree of interdependence among all the world’s peoples has grown considerably.

This interdependence can be seen in a number of realms:

- In the need to protect our climate from major anthropogenic (or, as Jason Hickel described it in Less Is More, capitalogenic) climate change.

- In the need to prevent at all costs a nuclear apocalypse, preferably through joint international action to dismantle all nuclear arsenals.

- In the need to coordinate closely on biosecurity and cyber-security.

That’s why I strongly welcomed the recent concept paper from China’s government on their Global Security Initiative. (On nuclear-arms issues, however, I wish it had gone further than calling merely for strengthening the NPT and had come out clearly for backing the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons.)

Ever since the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962, it has been clear that—as the leaders of the five nuclear-weapons states jointly reaffirmed in January 2022, and as China’s GSI document also spells out—”a nuclear war cannot be won and must never be fought.”

This fact has major implications regarding not just the (dis-)utility of nuclear arsenals but also the potency of military strength more broadly. In today’s world, military conflicts can no longer be fought “to the bitter end.”

Throughout the millennia prior to the 1945 dropping of nuclear bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, it was always plausible to believe that wars could be fought to the bitter end, and political leaders everywhere made their plans accordingly—though the savviest and longest-lasting among them were also attentive to other elements of national or imperial power, such as raw economic capabilities, the maintenance of domestic stability, the avoidance of plagues like the Black Death, and so on.

But in today’s world, economic strength increasingly outperforms raw military strength. And this is true even regarding the deadly, ongoing confrontation in Ukraine. In Ukraine, economic strength is already deeply relevant to:

- the ability of both warring parties to harness enough raw manufacturing capacity to keep needed military supplies flowing to the battlefields, and

- the ability of Russia to withstand the harsh economic punishments the United States has been trying to inflict on it.

… And then, in the context of any post-ceasefire situation in Ukraine, the economic capacities of both sides will be absolutely key to their successful rebuilding and recovery.

We have to remain confident that there will be a post-ceasefire situation in Ukraine—and absolutely, the sooner the better. At that point, while diplomats from all relevant parties get down into the weeds of what a more durable peace in that region can look like, I hope that leaders and publics all around the world can turn their (our) attention to what kind of a world we want to build for the remainder of our century.

In the last century, world leaders had three major “post-conflict” chances to build a better world order. The first, in 1918-19, they botched badly—principally through the insistence of the victorious Allies on endlessly “punishing Germany, punishing Germany”. We all know where that led… In 1945, much wiser heads prevailed, not least because the leaders of that era had lived as adults through the preceding 25 years and viscerally understood the need for a more generous, inclusive, and dare I say “rules-based” approach. Then in 1991, the Cold War ended with the collapse of the Soviet Union; and soon thereafter a youthful new president in Washington paid little heed to the lessons from earlier decades and set out to entrench and flaunt America’s primacy unabashedly on the world stage…

When this conflict in Ukraine ends, let’s hope that leaders and publics around the world can do what we need to do. We need to build the kind of redesigned and robustly multipolar world that Jeffrey Sachs, the Chinese government, and numerous others from (principally) the Global South have been increasingly loudly calling for.

Why did the US-NATO start a bloody War against Yugoslavia? Ukraine is a very similar entity, made up of some half dozen nationalities/territories; Russian, Polish, Hungarian, Rumanian, Moldovan, Byelorussian and now the US-NATO is supporting a bloody conflict-WAR, to avoid the same JUST fate that should be given to the Ukraine, if we want PEACE in Europe, and to avoid a possible Nuclear Armageddon! Why is the Ukraine so important in its current shape and form? Give the territories, populations back to the respective, Mother/Fatherlands and PRESTO, no more suffering and dying and Peace will return to Europe! Who are against such a JUSTIFIED outcome? WHY?

Your reframing of Biden’s bipolar fight to a multipolar reality is so critical for Americans (and our members of Congress) to understand. How, how, how do we convince the mainstream media to reframe?

And I listened to your comments about the history of armistices on the Code Pink (2/21) zoom … and I’m wondering how to move your comments from YouTube into the U.S. Capitol. Any ideas?

Thanks, Lora. I’m not sure that most members of the political elite here (members of Congress and the corporate media…) are yet at all open to thinking about either (a) the loss of US hegemony in the world or (b) how to *negotiate a ceasefire* in Ukraine. But we just have to keep on hammering out our ideas and suggestions. Of course, one of the massive problems is the degree to which what passes for a “left” in this country has become very accustomed to US hegemony and has drunk all the Kool-Aid about the US having a unique, “humanitarian” role in the world, etc, which may require “interventions” (by the US military) here or there… Another dimension is the partisan polarization over the matter of Russia, with the Dems now deeply anti-Russia. Sigh.

Personally, I find it’s really good to continue connecting with voices & friends from the Global South whose view of international affairs has for a while been much more grounded, sane, & compassionate than those of many US “progressives”.

Besides Sachs, I think you should also include and comment on the writings and discussions between Radhika Desai and Michael Hudson about what Marx has to contribute, their views on a multipolar world, and the nature of capitalism now as it moves from neoliberalism to economic nationalism. The new book by Desai, Capitalism, Coronavirus and War, with its attention to the role of the left and struggles for public ownership, decommodification of land , labor and money gives me hope.