The image above shows Saudi Arabia’s King Faisal and Pres. Nixon, on the White House lawn in 1971, the year Nixon unpegged the dollar from the gold standard

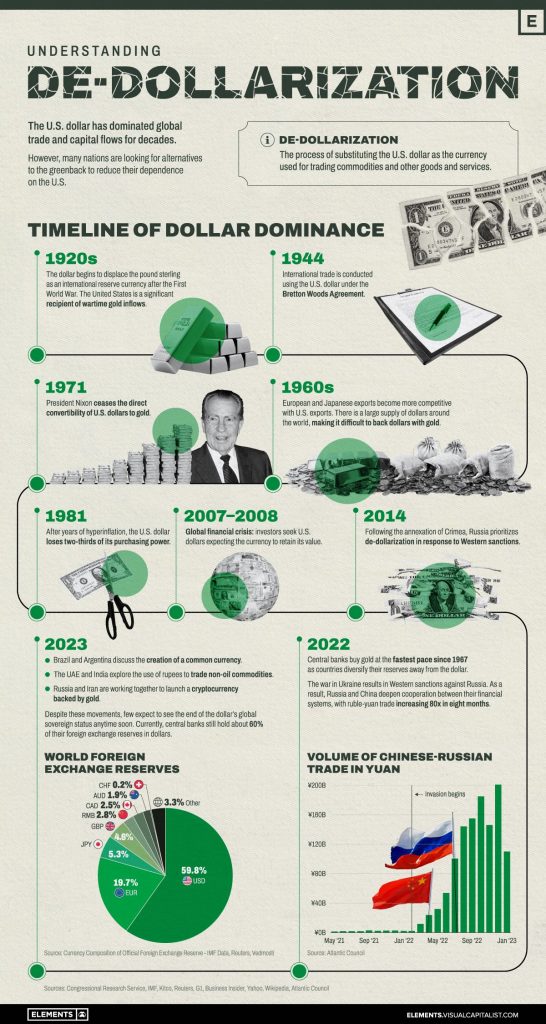

De-dollarization — that is, the choice that countries in the Global South have been making to conduct their trade in currencies other than the U.S. dollar — is a growing global phenomenon. It has profound implications for the economic situation in not just countries of the Global South but also Europe and (especially) the United States. It is a trend that strikes at the heart of the hegemonic, dollar-dominated “world order” that has existed since 1945, and is a key marker of the ongoing shift toward multipolarity.

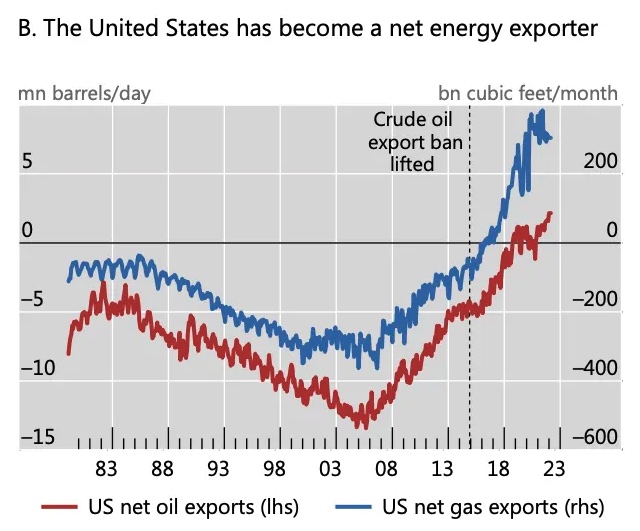

De-dollarization is intimately linked to developments in the world hydrocarbons business, including the decision U.S. elites made more than a decade ago to increase domestic shale-oil drilling, which over the years transformed the United States from a net importer to a net exporter of oil and gas products. That shift acted as a key catalyst spurring countries in and far beyond West Asia to base their trading relationships on currencies other than the greenback. The shift also upended Washington’s relationships with key oil producers in West Asia, which then provided a significant opening for the expansion of China’s influence in that vital region.

Those trends were all discernible before 2022. But when Washington (responding to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine) slapped harsh sanctions onto Russia, it boosted all of them into an overdrive that now looks poised to radically transform not just the global economy but also the global power-balance as we have known it since 1945. In this essay, I’ll quickly pull together what some key thinkers from North America, Europe, West Asia, and elsewhere have been writing about the current push toward de-dollarization and its impact on world affairs.

1.

One of the latest pundits to weigh in on the impact of de-dollarization has been Frank Giustra, co-chair of the influential, West-dominated Crisis Group think-tank. In a May 3 article at Responsible Statecraft, Giustra made the powerful argument that the United States’ true strength in international affairs lies not in its military but in the role of the dollar.

He wrote:

With the U.S. dollar seen and accepted as the world reserve currency, America has the privilege to control the global financial system, run federal deficits without having to worry about consequences, and literally print trillions of dollars out of thin air.

This unique advantage also allows the U.S. to keep interest on its accumulated debt low and provide its citizens a standard of living that would not otherwise be possible. But how long will it last?

He noted the accelerating effect that Washington’s harsh sanctions on Russia have had on the trend to de-dollarize. As he noted, not only did the U.S. and its allies impose sanctions on Russia’s leader, they also froze the country’s U.S. dollar reserves and blocked its banks completely from the SWIFT global payments system.

Those steps, he warned, “put [other] countries on notice that they might be next. Financial systems are built on trust and, if they are weaponized, they lose the trust necessary to retain their dominance.”

Giustra is a very successful Canadian financier and a significant investor in one of the world’s largest gold-mining conglomerates (a fact that, in the circumstances, he or Responsible Statecraft should have noted?) He is clearly thoughtful, as well as smart. After describing several recent instances of countries invoicing their trades in commodities in currencies other than the dollar, he noted this:

The critical unanswered question is how the U.S. will respond to moves to de-dollarize. Any sudden decrease in U.S. dollar demand could… potentially trigger a U.S. dollar crisis leading to very high inflation, or even hyperinflation, and initiate a debt and money printing cycle that could tear apart the social fabric of society.

In short, any U.S. administration would ultimately consider any such de-dollarization moves to be matters of national security.

The central policy step he prescribed seems sound: “[C]redible and inclusive dialogue regarding a new global agreement should commence now, in which major economies consent to a new monetary system (perhaps backed by gold and/or commodities) by consensus, including the U.S.” (Regardless of the soundness of this prescription I do also note that he has an interest in expanding the role of gold.)

2.

Frank Giustra’s article is one of several that have appeared recently that explore not just the trend toward de-dollarization but also the contribution made to that process by deeper changes in the oil market — and, also crucially, by changes in the relationship between Washington and Saudi Arabia.

Giustra, for example, reviews the history of how, in 1971, Pres. Richard Nixon made the unilateral decision to de-link the dollar from the cost of gold to which it had been pegged since 1946, instead allowing it to float freely according to market forces. He helpfully links to a 2016 article in which Bloomberg reporter Andrea Wong documented how, in the midst of the Arab oil crisis of 1973–74, U.S. Treasury Secretary William Simon concluded a secret deal with Saudi Arabia’s King Faisal that would stabilize what at that point looked like an extremely shaky dollar.

Wong wrote that the basic framework of the deal they concluded was, “strikingly simple. The U.S. would buy oil from Saudi Arabia and provide the kingdom military aid and equipment. In return, the Saudis would plow billions of their petrodollar revenue back into Treasuries and finance America’s spending.” (A non-trivial portion of the dollars Saudi Arabia earned from its oil sales was plowed straight into U.S. military industries, to keep production lines for American military equipment economically viable through “purchases” the Saudis made for items they could never possibly use…)

The agreement that Sec. Simon nailed down had, Wong wrote, been kept secret for more than four decades — until she was finally able to get the relevant Treasury documents released under the Freedom of Information Act.

Wong’s article was a useful reminder that the term “petrodollar” is not not a reference to something other than the usual dollar, or to a subset of a special kind of dollars. Rather, the term “petrodollar” refers to the nature of the dollar itself, and the way it has been valued and stabilized ever since 1974.

But that compact between Washington and Riyadh, which had many clear military and political dimensions, as well as its financial dimension, has been seriously eroding for several years now. A good part of this erosion derives from the fact that the 1974 compact was always based on the assumption that the United States would be a net importer of oil, from Saudi Arabia and other big exporters. The U.S. would pay those oil-providers in dollars; and the largest and most significant of the providers — not just Saudi Arabia, but also most of the others, following the kingdom’s lead — would then keep the dollars they were earning within the U.S. economy.

However, a recent excellent study from the Bank for International Settlements (PDF here) documents the degree to which the U.S. is no longer a net importer but an exporter of oil and gas. This study, “The changing nexus between commodity prices and the dollar: causes and implications”, by Hofmann et al, also explores some of the very disturbing impacts this development has already been having on many countries of the Global South. (Hat-tip to Adam Tooze for this link.)

The BIS authors write that the United States, “became a net exporter of natural gas in 2017 and of oil in late 2019… Russia’s invasion of Ukraine reinforced these changes, as countries sought alternative energy sources to replace imports from Russia.”

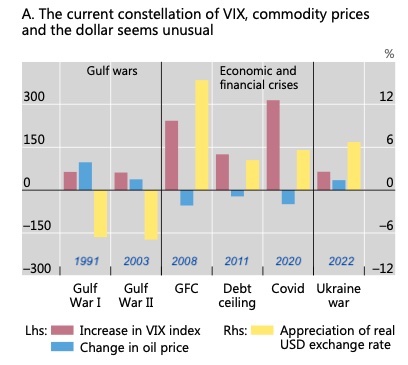

They note that previous periods of geopolitical uncertainty since the Gulf War of 1991 had always always seen the price of oil moving in the opposite direction to the U.S. dollar’s international exchange rate, as shown with the blue and yellow bars on the following graph. (The red bar shows the change in the VIX rate, a measure of economic uncertainty as manifested in the S&P index.)

The inverse relationship between the blue and yellow bars held right through the Covid crisis. But during the Ukraine crisis it has been broken, with both of them moving in the same direction. And this, the authors write write, has had huge consequences especially for those countries that are net importers of commodities (for which oil can, because of its heft in the global commodities market, be considered a synechdoche), and that pay for them in dollars.

During previous global crises, they explained, if the price of oil (and other commodities) went up, then the dollar exchange rate at which those net-importing countries would pay for their imports would go down, and vice versa. But that is no longer the case. “The change in the commodity price-dollar nexus implies that movements in the US dollar now compound the effect of commodity prices changes on the global economy,” they write. At a global-economic level, the whole period since Q1–2022 has therefore seen a very worrying combination of inflation and stagnation — stagflation — as shown in Graph A, the lefthand graph below:

If you look at the righthand graph (Graph B), you will see the differing effects that this situation had in 2022 on countries that are net importers of commodities versus the net exporters. (Most of the two-letter country codes under those graphs are clear. But here’s a complete list.)

Basically, both the net importers and the net exporters suffered an “inflation surprise” in 2022, that is, inflation was higher than had been forecast in October 2021. But in 2022 commodity importers saw both a decline in their terms of trade and a shortfall in their expected GDP growth, while commodity exporters saw increases in both those measures. (Neither Russia, RU, nor the United States, US, appears to be included in this graph. Russia, as we know is a massive net exporter of commodities and its economy performed considerably better in 2022 than Western leaders had forecast, and hoped, would be the outcome after their sanctions had been slapped on.)

Hofmann et al. conclude that,

Some commodity exporters may consider catering to the wishes of their new most important customers [that is, not the U.S.], as the stabilising impact of the dollar on their economies weakens. Commodity importers may welcome such a change if it shields their economies from the stagflationary effects of rising oil prices and dollar appreciation. Recent data lend some support to this notion. For instance, the major Gulf States have reduced their investments in US Treasury debt even as oil prices and, hence, oil export revenues have picked up (Graph 5.B), possibly indicating more non-dollar oil export invoicing. Moreover, the share of global trade invoiced in US dollars has declined from its peak in 2014 and the global share of foreign exchange reserves held in dollars has fallen to a three-decade low.)

These authors were cautious, however, in what they predicted about the dollar’s future role in world affairs: “[T]he debate on threats to the dollar’s status is not new and there are many reasons for the status quo to continue,” they wrote. “Whether the evolving energy and geopolitical landscape prompt a material change in the dollar’s global role remains to be seen.”

3.

Two recent pieces on the Lebanese news-site The Cradle provide additional helpful data on some of these matters. In one, roving correspondent Pepe Escobar provides some informative snapshots of various aspects of de-dollarization:

The numbers: the dollar share of global reserves was 73 percent in 2001, 55 percent in 2021, and 47 percent in 2022. The key takeaway is that last year, the dollar share slid 10 times faster than the average in the past two decades.

Now it is no longer far-fetched to project a global dollar share of only 30 percent by the end of 2024, coinciding with the next US presidential election.

The defining moment — the actual trigger leading to the Fall of the Hegemon — was in February 2022, when over $300 billion in Russian foreign reserves were “frozen” by the collective west, and every other country on the planet began fearing for their own dollar stores abroad…

Now cue to some current essential developments on the trading front.

Over 70 percent of trade deals between Russia and China now use either the ruble or the yuan, according to Russian Finance Minister Anton Siluanov.

Russia and India are trading oil in rupees. Less than four weeks ago, Banco Bocom BBM became the first Latin American bank to sign up as a direct participant of the Cross-Border Interbank Payment System (CIPS), which is the Chinese alternative to the western-led financial messaging system, SWIFT.

China’s CNOOC and France’s Total signed their first LNG trade in yuan via the Shanghai Petroleum and Natural Gas Exchange…

Later, he gives more details about the operations of the Shanghai Petroleum and Natural Gas Exchange, concluding that, “Dumping the dollar already has a mechanism: making full use of the Shanghai Energy Exchange’s future oil contracts in yuan. That’s the preferred path for the end of the petrodollar.”

The whole of Escobar’s piece is worth reading. As is this longer piece from Hussein Askary, which provides valuable background to the decisions that the present rulers in Saudi Arabia and the UAE have taken to turn away from their countries’ previously strong ties to the United States. It also provides a solid recap of the history behind very recent (and notably non-American) diplomatic breakthroughs that China, Russia, and Iran have all achieved in the region, several of which I have tracked here at Globalities in recent weeks.

Askary’s article starts boldly:

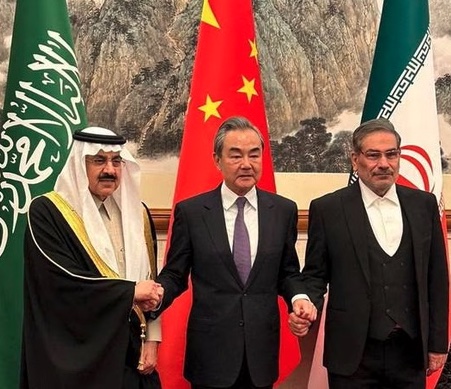

The recent normalization of relations between Iran and Saudi Arabia, brokered by China, is just the tip of the iceberg in terms of a larger paradigm shift in West Asia. Russia, Iran, and China (RIC) are all playing key roles in shaping this change, which could make Anglo-American interventions in the region obsolete.

Although Russia, Iran, and China are often viewed as enemies, rivals, or competitors by the west, they have emerged as the main powerbrokers designing exit strategies from many of the western-sponsored crises in West Asia.

While Russia and Iran have played more decisive military and security roles in this development, China has weighed in with its economic heft to bring to the fore this regional paradigm shift.

Askary’s article contains one map showing the locations of U.S. bases in West Asia, and another that shows the patrolling areas for the four NATO-led “Combined Maritime Forces” that the United States and its allies have unilaterally maintained since 1983 in all the waters surrounding the Arab Peninsula, as shown.

He traces China’s current diplomatic push in West Asia back to January 2016, when Pres. Xi visited Egypt, Iran, and Saudi Arabia. That visit, he noted,

took place as Saudi-Iranian relations hit rock bottom, with Riyadh’s provocative execution of Saudi Shia cleric Nimr Baqir al-Nimr just days before the Chinese president arrived in the region. The killing sparked protests in Iran, leading to the ransacking of Saudi Arabia’s Tehran embassy and the final break in diplomatic relations between the two key Persian Gulf states.

However, China’s friendly and increasingly close economic relationship with all three nations enabled it to become a trusted broker, coordinating separately with each to gradually strike comprehensive strategic agreements.

He wrote about the importance of a “Middle East Security Forum” held by the China Institute for International Studies in September 2022. (An earlier session of that forum had been held in Beijing in 2019. This report on the CIIS website notes that the 2022 session, “had two sub-forums on the Palestinian question and the security situation in the Gulf region.”) Then in December 2022, as Askary noted, Pres. Xi was in Riyadh to headline a China-Arab Summit.

All that obviously helps show the depth and seriousness of China’s diplomatic engagement with the West Asia region, which underlay its achievement in concluding the momentous rapprochement between Saudi Arabia and Iran, in early March…

Regarding the attempts Iran has made over the years to reach to Saudi Arabia, Askary wrote:

Iran has toiled for many years to create a joint security architecture with its Persian Gulf neighbors, particularly Saudi Arabia. Former Iranian President Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani successfully reached a 1997 security and cooperation agreement with Saudi Arabia’s then Crown Prince Abdullah bin Abdulaziz, which remained effective until 2005.

However, US policies in the region since the 2003 invasion of Iraq created an unbridgeable sectarian gulf in the region, placing Saudi Arabia and Iran on different sides of a chasm that has been described as the ‘Shia Crescent’ versus the ‘Sunni Triangle’…

In September 2019, Iranian President Hassan Rouhani proposed the Hormuz Peace Endeavor ( HOPE) at the UN General Assembly, which aimed to bring together the littoral states of the Persian Gulf — the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), plus Iran and Iraq — around a common framework for security, freedom of navigation, and economic cooperation. However, with the persistent US targeting of Iran, this initiative was not feasible.

It is crucial to note that the US assassination of Iranian Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corp’s (IRGC) Quds Force Commander Qassem Soleimani took place in the Iraqi capital of Baghdad on 3 January, 2020 while he was carrying a message from Iran’s Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei to the Iraqi Prime Minister, including a response to Saudi inquiries. (My italics there, HC.) At that time, then-Iraqi Prime Minister Adil Abdul-Mahdi was mediating communications between Tehran and Riyadh to reach understandings.

Several other accounts also have noted that, of the regional states, Oman as well as Iraq played a helpful role in mediating Iranian-Saudi differences.

For his part, Askary wrote that, “Iran’s current President, Ebrahim Raisi, has continued to support HOPE, achieving an important breakthrough when diplomatic relations with the UAE at the ambassadorial level were restored shortly after Raisi assumed his post in August 2021.”

He wrote that,

the Saudi-UAE foreign policy shift and their surprising divergence with the policies of Washington have been simmering below the surface for several years, awaiting a catalyst.

The GCC countries have realized that the “Arab Spring” did nothing but create regional divisions and deplete vital national resources. Regional influencers prior to the seismic 2011 events — such as Qatar, Turkiye, Iran, Syria, the UAE, and Egypt — were sucked into dangerous adversarial positions with no upside.

While Riyadh and Abu Dhabi’s services and wealth were welcome in destabilizing Syria, Libya, Yemen, and Iran, their own political and economic interests were not of paramount concern to Washington.

Although the Syrian crisis began to wind down, courtesy of Russian intervention and mediation, the Saudis and Emiratis became bogged down in an expensive quagmire in Yemen, now in its eighth year.

Further, the economic interests of Persian Gulf energy producers and Washington began to clearly diverge after the onset of the Ukraine war in February 2022, when OPEC+ states decided to curb production in order to maintain high oil prices against the wishes of the US and Europe.

He concluded by commenting on another consequence of the United States’ buildup of its shale-oil exploitation and exports that had been highlighted in Hofmann et al.’s report:

[T]he US — which has long sought to reduce reliance on West Asian oil and has spent decades building up its domestic shale industry — has little energy synergy with Persian Gulf producers, whose interests increasingly intersect with Russia and China on the oil and gas front…

The US has lost the trust of its long-time allies in the region, its influence is waning fast, and the dollar — the global reserve currency — is now under attack…

While it remains to be seen how the new Eurasian powers will shape the future of Persian Gulf security, several things are clear: Regional states are winding down their conflicts with new intermediaries; their collective and domestic focus is economy and development; reconciliation has become de rigeur for all; and none of these priorities require the astronomical military expenditures and western armed forces/bases that characterized Persian Gulf “security” of years past.

As the Persian Gulf littoral states begin to test their new friendships and incrementally build up trust in each other, it will be left to genuine, impartial mediators like Russia and China to bridge gaps in understandings and troubleshoot when incidents arise. These will take place at a table — not in a military arena — and be accompanied by trade deals that boost mutual wealth creation and development, rendering the old “guarantors” of Persian Gulf security entirely obsolete.

4.

This series of developments provides some real hope that, as China, other BRICS members, and key commodities exporters like the oil states of the Persian Gulf region continue to build stronger economic ties among themselves— and ties that are increasingly independent of the pressure that Washington has been able to exert on the economies of so many countries through its command of the global dollar system— the role of military force in world affairs can become substantially curtailed.

However, the Crisis Group’s Frank Giustra was also right to warn, as he did in his recent piece, that, “History has demonstrated that it is exceptionally rare for a transfer of global economic power to take place without major warfare.”

The solution that Giustra proposes for this significant challenge that he identified is that all-party negotiations should start “now”, over how to build the new monetary system he envisages… But he adds very cautiously that, “The best we can hope for is a process that facilitates the gradual decrease in dollar demand over a lengthy period of time, allowing the U.S. and other countries to adjust accordingly…”

As a citizen of the United States I say that moving away from the (petro-)dollar’s dominance of the global economy gradually is not good enough. We need to end this dominance as fast as we can. To do that, we’ll need to build a movement here in the United States made up of citizens committed to global fairness and to completely renouncing the many advantages that the petrodollarized world economy has afforded to us for so many decades now.