First, a quick disclosure: As someone extremely fond of the young people in my family, I am deeply concerned about the effect of all social media apps on the lives and psyches of tweens and teens. Not just TikTok, but all of them…

So now, on to TikTok and the outrageous spectacle of the hearing the House of Representatives Energy and Commerce Committee held yesterday into alleged harms that it accused the Chinese-owned company of inflicting on Americans. And no, the spectacle there lay not just in the stunning ignorance some committee members displayed about the basics of the technology they were allegedly investigating… It lay even more in the sad parade of unthinking, anti-China prejudice that they modeled and amplified in their remarks.

Few of these elected representatives showed any interest in actually listening to, or learning from, the answers that TikTok’s ever-patient (and by the way, Singaporean) CEO, Shou Zi Chew, gave to their often baffling questions. The reps were too busy grandstanding for the cameras and for the national audiences that they assumed would just love to see them strut on the big Sinophobic stage that this five-hour hearing afforded them. (Big kudos to NY Rep. Jamaal Bowman, who was the only member of Congress prepared to stick up for TikTok and to question the anti-China nature of the hearings.)

Within the broader “blob” of today’s Washington political elite, anti-China agitation is now, all too often, a quite bipartisan affair. But why? I don’t necessarily expect every member of the House Energy and Commerce Committee to be conversant with the writings of Clausewitz, Sun Tzu, Bernard Brodie, Henry Kissinger, or other great strategic thinkers. But I would hope that the relevant leaders of our national-security apparatus might have given serious thought to such matters… especially in the age of possible nuclear annihilation that we’ve been living in for 78 years now.

But no.

At a time when U.S. taxpayers are pouring billions of dollars into a fight against Russia in Ukraine that has had devastating effects around the world—including on humankind’s ability to deal with the amply demonstrated horors of climate change—and when our country’s national-security team is fixated on confronting Russia in every domain, the leaders of this team are also leading a campaign to simultaneously confront China.

This current anti-China campaign is quite bipartisan. Donald Trump may have initiated the fight against China with his unjustified imposition of tariffs on broad swathes of Chinese imports, and then with the Sinophobia he displayed at the start of the Covid pandemic. But Joe Biden then kept all the tariffs in place, and has planted his own, sharply anti-China provisions deep into the country’s military planning documents. (Did I mention my admiration for NY Rep. Jamaal Bowman, for daring to buck the anti-China trend?)

Just this past week, Sec. of State Anthony Blinkered, oops, Blinken, was earnestly telling a Senate committee about, “the immediate acute threat posed by Russia’s autocracy and its aggression against Ukraine, and the long-term challenge from the People’s Republic of China.”

But really, Blinken, Sullivan, and Co: It is surely not outrageous for us to expect you to understand some of the basics from Clausewitz’s “On War”? Such as don’t gratuitously take on two big enemies at the same time if there’s a chance to split them apart. Sigh.

Actually, at the level of “strategic” thinking I’d even give slightly higher marks to those in the Republican Party who want to stoke up a confrontation with China and seem as if they would be happy to cut a quick deal with Russia on Ukraine if it would help them achieve the anti-China pivot they seek.

But those GOP outliers aside, how did we get into this situation of so many members of both U.S. parties lining up to stoke ever-sharper confrontations with both Russia and China at the same time?

To help us understand some of the intricacies in the swaying dance conducted by the three tallest tent-poles of the post-1945 world, I’ve prepared the following little listing of some of the key turning points. (And yes, this is exactly the kind of chronology that journalists like to call a “tick-tock”.)

1949:

1949 saw two momentous developments in the trilateral relationship:

- In late August, the Soviet Union held its first successful nuclear-weapons test, breaking the monopoly on nuclear-weapons possession that the United States had enjoyed since 1945.

- Then, on October 1, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) was finally victorious in the punishing, decades-long civil war it had been fighting against the Nationalist Chinese known as the KMT. CCP leader Mao Zedong proclaimed the establishment of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) on the whole of the Chinese mainland. The remnants of the KMT fled to Taiwan. The KMT’s collapse was deeply shocking to nearly the whole of the Washington establishment.

1950-53:

The (also very punishing) war on the Korean peninsula fought during these years pitted Chinese-backed North Korea against U.S.-backed South Korea. During the war, the U.S. “Supreme Allied Commander of the Pacific”, Gen. Douglas MacArthur, urged Pres. Truman to use nuclear weapons against the China, if necessary.

The Chinese, who had no nuclear weapons of their own, were not deterred.

In 1951, the parties to the Korean fighting started negotiating a countrywide ceasefire, or armistice. The negotiations took two years. When the armistice was finally agreed in 1953, the signatories were the local commanders of the North Korean, Chinese, and American forces. (The South Koreans never signed, but profited mightily from the decades of near-calm that followed.)

1961-62:

This period saw several big developments in the balance among the world’s three big tent-poles:

- In 1961, a series of disagreements that had long been simmering between the ruling parties in Moscow and Beijing spilled into the open. These disagreements included a judgment the Russians had held that Mao’s continuing actions against the KMT regime in Taiwan were far too risky; disputes over relations with India; and a deep disagreement over Josef Stalin’s legacy. Throughout the 1950s, these two big ruling Communist parties were increasingly competing for the support of allies and comrades around the world. Then, in 1961, their split became quite deep, and public for all to see…

- In fall of 1962, the Cuban Missile Crisis brought the Russians and Americans the closest they had ever been to falling headlong into full-scale nuclear war. (As has been chillingly chronicled by Daniel Ellsberg.)

- That crisis was resolved through a speedily arranged series of top-level negotiations. The shock in both Moscow and Washington over how close thy had brought the whole world to nuclear annihilation spurred them to launch talks on how to assure control of the terrifying nuclear arsenals at their command; and a lengthy series of bilateral arms-control agreements were negotiated over the 25 years that followed.

- Chairman Mao, meantime, was not happy about the what happened during and after the Cuban Missile Crisis. In later 1962, the PRC broke off relations with the USSR completely, with Mao angrily claiming that “Khrushchev has moved from adventurism to capitulationism.”

1964:

In the context of the now-open Sino-Soviet split, Mao accelerated his engineers’ work on developing China’s nuclear bomb. In October 1964, China conducted its first nuclear-weapons test at Lop Nor.

1972-79:

Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, most participants in the American public discourse were terrified by the bullying tactics of the deeply anti-communist Senator Joe McCarthy. There was also a pervasive and accusatory furore over who in Washington had “lost” China to the Communists. Under those circumstances, it probably took a politician with the rightwing credentials of Pres. Richard Nixon to reach out and start restoring the relationship with Beijing that had been so abruptly broken in 1949.

In February 1972 Nixon undertook his landmark visit to Beijing, which set in train a slow but steady rapprochement between the two governments.

That rapprochement helped Washington to manage the strains it faced at home and overseas over its conduct of the war in Vietnam (in which both Moscow and Beijing continued to aid North Vietnam.) The rapprochement also gave Washington additional clout and freedom of action as it continued to conduct its arms-control diplomacy with Moscow.

In 1979, in a culmination of the U.S.-China rapprochement, Pres. Jimmy Carter and Beijing’s new supremo Deng Xiaoping agreed to restore full diplomatic relations. Carter announced the United States’ adoption of the “One China” policy, which involved downgrading its relationship with Taiwan to something less than full diplomatic recognition.

Throughout the 40 years that followed the mid-1970s, trade and other economic ties between China and the United States increased steadily. By the turn of the millennium these ties had come to function as the driving engine of most of the global economy.

1989-93:

Under its increasingly sclerotic Communist leadership, the USSR could not keep up economically. In late 1989, the Soviet empire in East and Central Europe started to crumble. Its “Warsaw Pact” fell apart; and then, so did the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics itself.

Throughout the 1990s, Russia’s chaotic and U.S.-backed leader, Boris Yeltsin, presided over the dismantling of much of the country’s economy under the guise of privatization and globalization.

1999-2000:

In late 1999, with Yeltsin’s alcoholism ever more debilitating, he proposed—with support from Washington—that his prime minister Vladimir Putin should replace him as president. Putin then started the series of terms in office in Moscow (as both president and prime minister) that have marked the whole era since then.

During his first 22 years in power Putin did much to stabilize a national economy and society that Yeltsin had left in turmoil. At first, he continued to try to link Russia’s economy with that of the European Union. And in late 2001 he helped Washington gain significant access to resupply routes through Central Asian nations for the suddenly massive U.S. military presence in landlocked Afghanistan…

2003-05:

By many accounts, Putin found Washington’s (quite unauthorized and unlawful) invasion of Iraq in 2003 deeply disturbing. At around the same time, the National Endowment for Democracy, which is a key U.S. tool for fomenting regime-change projects around the world, expanded its funding for anti-Russian movements in Ukraine, Georgia, and elsewhere around Russia’s periphery. These developments curbed Putin’s willingness to continue pushing for more integration with “the West”—at a time when China’s leader, Hu Jintao, was still enthusiastically pursuing such engagement.

2017-21:

So then, as I’ve chronicled above, along came Donald Trump and the sharp turn he led against China. Trump’s shift was then continued by Pres. Biden, who deepened its effects both in the realm of military planning and through taking serious steps toward decoupling the two economies that over the course of decades past had come to appear so tightly linked…

2022:

And then, came Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. The invasion has placed China in a tough spot, since its leaders remain wary of any moves toward the secession of countries’ outlying areas, such as Russia has been actively supporting in Ukraine. China is also deeply committed (on paper) to the resolution of conflicts through negotiation.

But the invasion and its sequelae have also enhanced China’s standing in world affairs in several ways. Crucially, in a period when the political winds in Washington were anyway blowing strongly against China, the global divide spurred by the conflict in Ukraine gave new strength and relevance to non-Western international bodies like the Shanghai Cooperation Organization and the BRICS grouping, in which China, Russia, and significant countries from the Global South together hold sway…

So what conclusions can we draw from my little “tick-tock” here?

One is a recognition (however hard it is to swallow) of the strategic acuity of Richard Nixon, when he (1) recognized the seriousness of the Sino-Soviet split that had occurred in the 1960s and (2) decided that he could exploit it to the United States’ benefit by reaching out to China and actively using this new relationship with an unabashedly Communist power as a means to (essentially) get what he wanted from the Soviet Union. All that, while also radically expanding the market for U.S. goods and services. What’s not to like?

Another conclusion is to underline even further (if only by contrast) how very short-sighted are the current parade of people sitting at the driving-wheel of U.S. power.

Back in Nixon’s 1972, of course, the United States’ heft in world affairs was still considerably larger than it is today. But then, any elementary reading of Clausewitz would indicate that the need for strategic smarts (wiliness) is actually that much more important for weaker or weakening powers than it is for stronger ones.

Meantime, as the members of the U.S. Senate and House committees were conducting their various hearings this week, in Moscow a much more momentous series of meetings were being held. These were the many hours of face-to-face meetings, held over the course of three days, that Pres. Xi Jinping and his large entourage held with their Russian counterparts.

In Moscow, the two leaders signed two agreements: one on “Deepening the Comprehensive Strategic Partnership of Coordination for the New Era” and one on “Priorities in China-Russia Economic Cooperation.” In China’s English-language readout from the meetings, it stated that the two presidents, “shared the view that this relationship has… acquired critical importance for the global landscape and the future of humanity.”

The readout concluded with this:

The two sides will boost the constructive force for building a multi-polar world and improving the global governance system, contribute more to maintaining global food and energy security and keeping industrial and supply chains stable, and work together for a community with a shared future for mankind.

President Xi stressed that, last month, China released a document titled “China’s Position on the Political Settlement of the Ukraine Crisis”. On the Ukraine crisis, China has all along abided by the purposes and principles of the UN Charter, followed an objective and impartial position, and actively encouraged peace talks. China has based its position on the merits of the matter per se and stood firm for peace and dialogue and on the right side of history.

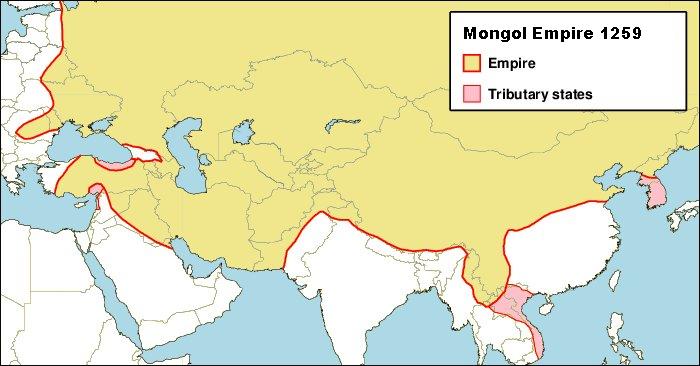

No word yet, and understandably so, on how deeply the presidents dove into the weeds of any concrete plans for peacemaking or an armistice in Ukraine. But meantime, the increasingly close relationship between their countries seems set to bring to Eurasia’s (truly massive) landmass an era of political accord that it has not seen since the Mongol leader Möngke Khan died in 1259. (That empire did not last long but was soon split amongst his brothers and heirs.)