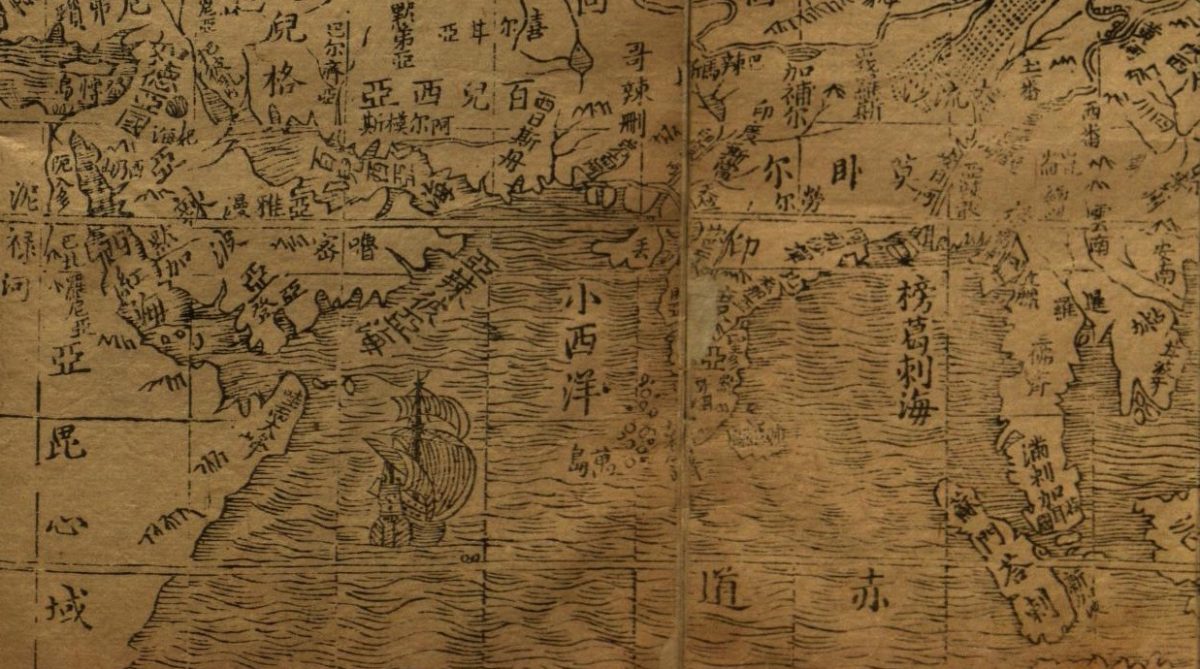

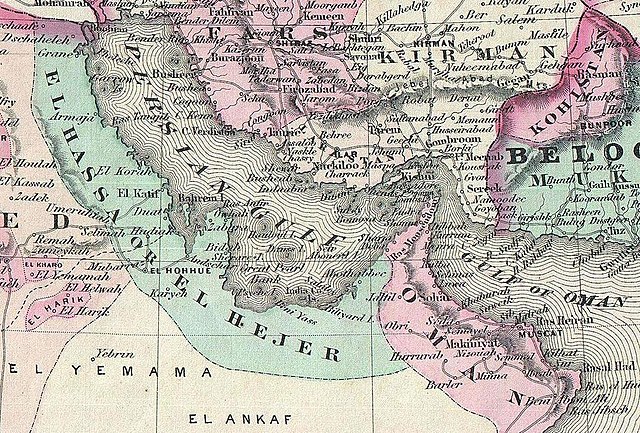

(An early 17th century Chinese map of part of the Indian Ocean, using data gathered by Zheng He’s voyages of 200 years earlier. The Arabian Peninsula is at the left. Source.)

Over the past couple of months, in my essays here at Globalities I’ve been tracking the current crumbling of the decades-old system of Washington’s global hegemony and its gradual replacement by a China- and BRICS -led system of multipolarity—and also some of the effects of that shift, in West Asia and elsewhere. Most recently, we’ve seen China’s President Xi Jinping pushing forward his previously announced readiness to help resolve the conflict in Ukraine. If successful, this initiative could bring about a further large diminution of U.S. power in the world.

We should all continue watching the progress of the China-led peace initiative for Ukraine very closely. In today’s essay, however, I want to explore some of the impact that this “West to the Rest” shift has already been having in West Asia (the region formerly known as “the Middle East”), and especially in and around the Arabian Peninsula.

Until recently, all the states of the Peninsula, with the exception of some substantial quasi-state actors in mountain-haven Yemen, have been unambiguously pro-American. The other states on the Peninsula are all wealthy petro-states. They have long maintained strong relationships with Washington under an arrangement whereby the United States promised to give them military protection provided they would continue to underwrite the U.S. military-industrial complex by buying large (and often quite unusable) inventories of U.S. weapons, and to support the role of the U.S. dollar in the global economy.

But in recent years, and even more rapidly since last year’s start of the big conflict in Ukraine,that “devil’s bargain” has started to fall apart. As Jon Alterman wrote recently about the region in Defense One:

The [U.S.] military starts from the premise that the pax americana that U.S. dollars and U.S. soldiers helped secure has kept the region from tipping into chaos, and they offer more of the same. But many governments in the region think that the region has already tipped into chaos, and that the United States has been a central part of the problem.

As Alterman and others have noted, one of the key recent factors underlying the skepticism with which many of the Arab petro-state rulers have come to view U.S. plans for the region has been Washington’s nagging insistence that these states stay on its “side” as it maintains high levels of tension against both Russia and China. (And the fact that Pres. Biden has been doing this in the name of a harshly ideological, democracies-vs-autocracies framing has not, to say the least, proven very persuasive for the petro-monarchies…)

Today, the states of the Arabian Peninsula don’t want to be forced to choose between the West and the Rest. Instead, they have been calmly working on strengthening their ties with anyone else in the world that they choose to.

Saudi Arabia is the most consequential of the Peninsula states that have been resisting Washington’s pressure to hew to a pro-Washington, anti-Moscow, and anti-Beijing line. Crown Prince Mohammad Bin Salman (MBS) and his foreign minister have consulted closely with the leaders in Moscow and Beijing on several issues over recent years.

In February, MBS refused to bow to U.S. entreaties to keep the Kingdom’s oil exports high. Instead he —along with the UAE’s President—chose to coordinate with Russia on restricting exports to keep global oil prices high. Then last month, Saudi Arabia announced a crucial (and Chinese-mediated) rapprochement with Washington’s regional bête-noire Iran, following it up with serious moves to de-escalate the damaging conflicts it had long pursued against Iran’s allies in Yemen and Syria…

Meanwhile, at a broader global level, Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Egypt, and Bahrain are all—along with Algeria and Iran—among the 13 states that have expressed a desire to join the BRICS grouping. Given the role that these states play in the world system, this shift in their posture is huge.

For several millennia now, the Arabian Peninsula has occupied a crucial, “hinge” role in the systems of trade and cultural exchange that spanned the whole of the pre-Columbus “known world”. Long before the peoples of the Arabian Peninsula and the rest of West Asia had their lives transformed by the discovery of oil in their lands, they had been leading participants in trading relationships that wove all across the Indian Ocean from Africa to China, and that connected the riches of those regions with the (later-developing) cultures of the Mediterranean and Black Sea basins.

Today, increasing numbers of Arab leaders are returning to, or deepening, that older connection to the commerce and culture of the Greater Indian Ocean area. As they do so, they are opting out of the highly militarized, “us-versus-them” approach to world affairs that the (geographically distant) United States and its allies have become obsessed with. And they’re returning to the older, more inclusive and laissez-faire traditions of the Indian Ocean’s traditional systems of trade and communication.

In the rest of this essay I’ll take a deep dive into the history of the Indian Ocean’s pre-European networks of maritime trade and cultural exchange, a new version of which we can now see starting to emerge. In a later essay, I hope to explore why the re-emergence of this more multi-polar system could signal a sharp reduction in the usability of military force not just in the Indian Ocean but also worldwide.

The United States of America sits on a large landmass that is far distant from both the European and the Asian ends of Eurasia. The United States is even further from the Indian Ocean, which for millennia was the central hub of all international commerce. (Kansas City is located almost exactly 180 degrees of latitude distant from Sri Lanka.)

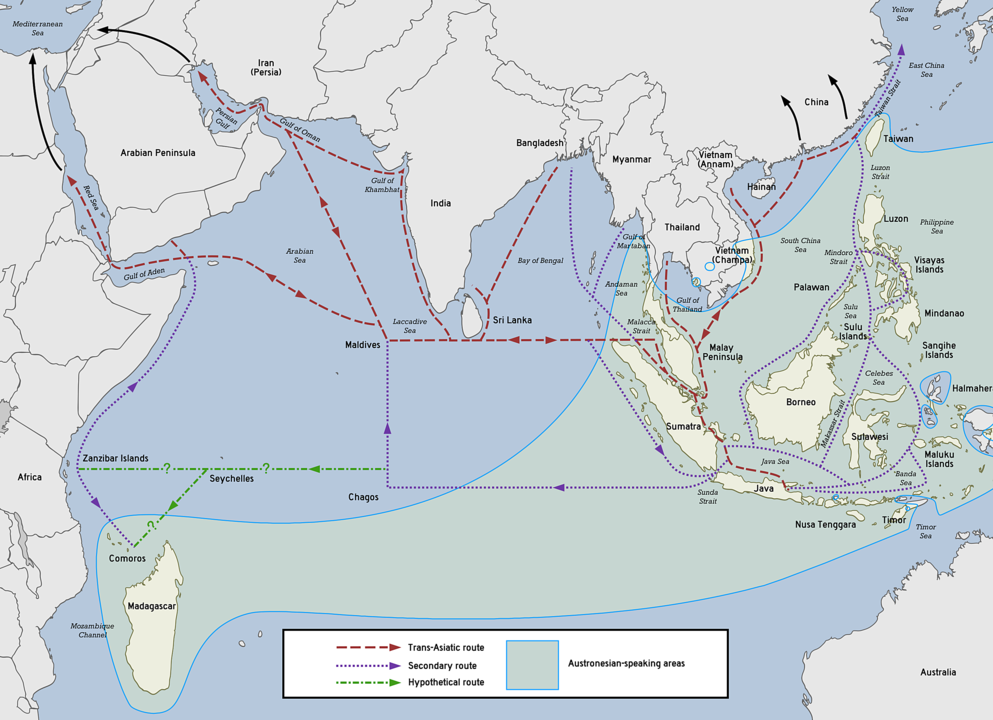

Probably the first peoples to navigate long distances across the Indian Ocean were expert Austronesian navigators, who in around 500 BCE established trade ties between the “Spice Islands” of the Indo-Pacific, Sri Lanka, Southern India, Madagascar, and the rest of the Indian Ocean rim.

Soon thereafter, in 330 BCE, the ocean’s northwestern coast saw the historic entry of the Macedonian Greek, Alexander the Great, whose super-capable land armies carved out an empire that incorporated all of today’s Iran and much of Afghanistan and Pakistan. In 325, Alexander did send a fleet sailing from near today’s Karachi, hugging the coast back to near today’s Basra. But nearly all of his conquests and the administration of his empire was conducted via land routes. He died in 323 in Babylon, Mesopotamia.

Alexander’s general (and possibly also half-brother) Ptolemy then set himself up as ruler in Egypt, and pursued his new kingdom’s trade with the Indian Ocean basin via the Red Sea. Those trade links grew mightily and flourished!

This section in Wikipedia notes that:

The Ptolemaic dynasty (305 to 30 BC) had initiated Greco-Roman maritime trade contact with India using the Red Sea ports. The Roman historian Strabo mentions a vast increase in trade following the Roman annexation of Egypt, indicating that monsoon was known and manipulated for trade in his time. By the time of Augustus [27 BCE] up to 120 ships were setting sail every year from Myos Hormos [a Red Sea port] to India, trading in a diverse variety of goods…

In a recent issue of the New York Review of Books, Will Dalrymple reported on the recent discovery in a currently desolate spot on Egypt’s Red Sea coast of what he described as, “the head and torso of a magnificent Buddha, the first ever found west of Afghanistan.” He quoted the director of the dig that found it as suggesting that, “it was probably commissioned by a wealthy Indian Buddhist sea captain in thanks for his safe arrival in the Roman Empire.” (Go read the whole of his fascinating article, if you can.)

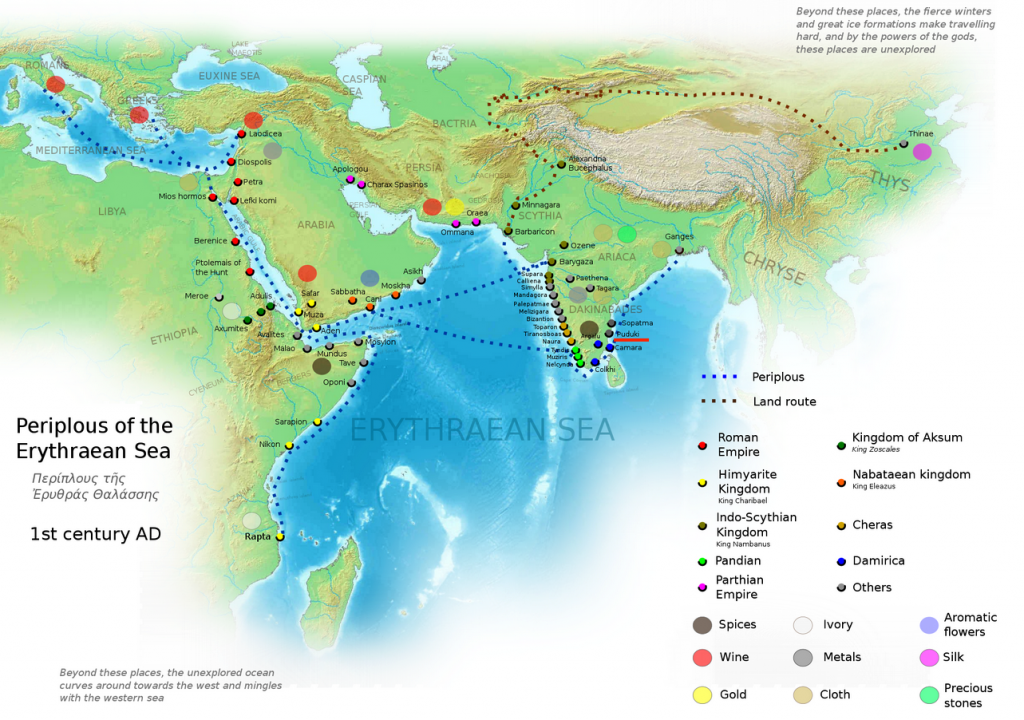

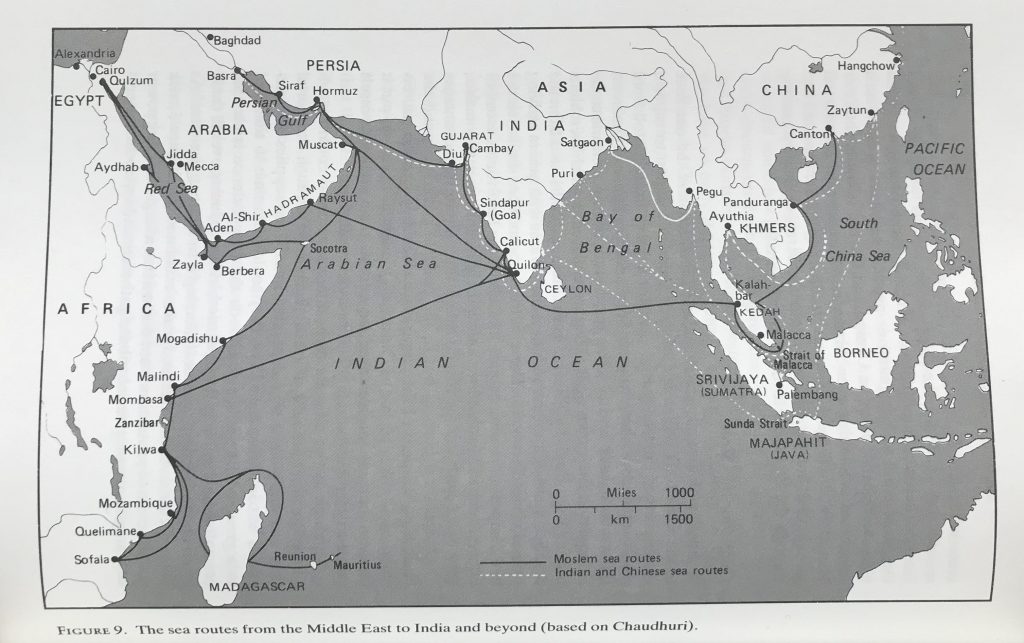

In the 1st century CE, a Graeco-Roman guide to trading opportunities in what it called the “Erythraean Sea”—now known as the Arabian Sea portion of the greater Indian Ocean—provided the information charted in this later map (shown).

Small wonder that after Nestorian Christianity became common at the Western end of those routes, it also traveled east along them, leading to the early establishment of Nestorian churches in Southern India and also (perhaps surprisingly) the later adoption by Mongol rulers of a verticalized version of the Nestorian/Arabian script for writing their own national language.

And later, as we know, came the expert Muslim navigators from the home-bases along both coasts of the Red Sea, both coasts of the Persian Gulf, and the southern coast of today’s Yemen/Oman. These Muslims were even better traders—and much better proselytizers for their faith!—than their Graeco-Christian predecessors. Janet Abu-Lughod’s 1989 book Before European Hegemony: The World System A.D. 1250-1350 provides this great map of the main Muslim and other sea routes in the Indian Ocean during that century her book was covering:

The descriptions Dr. Abu-Lughod provided of the arrangements under which all the participants traded made clear that in most ports, merchants from anywhere else in the system were equally welcome, and the terms on which they traded were freely negotiated. As she, Will Dalrymple (in this second work) and others have noted, it was also a period of very rich cultural exchange.

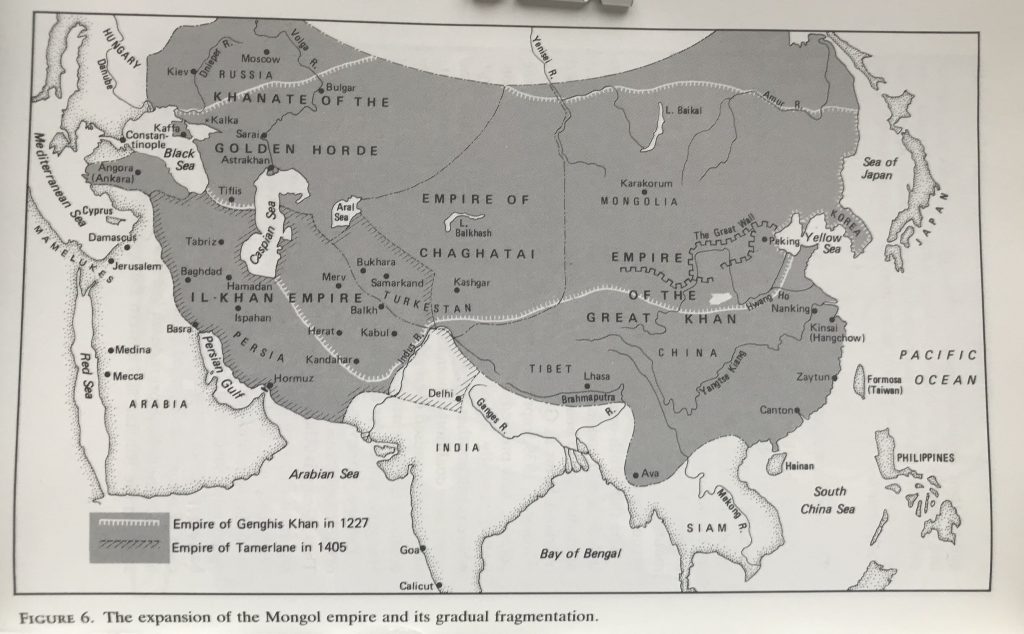

And these interactions were conducted not only by sea. During the 13th- to 14th-century, in particular, a Pax Mongolica allowed sustained (though never easy) interaction by land across north and central Asia, too.

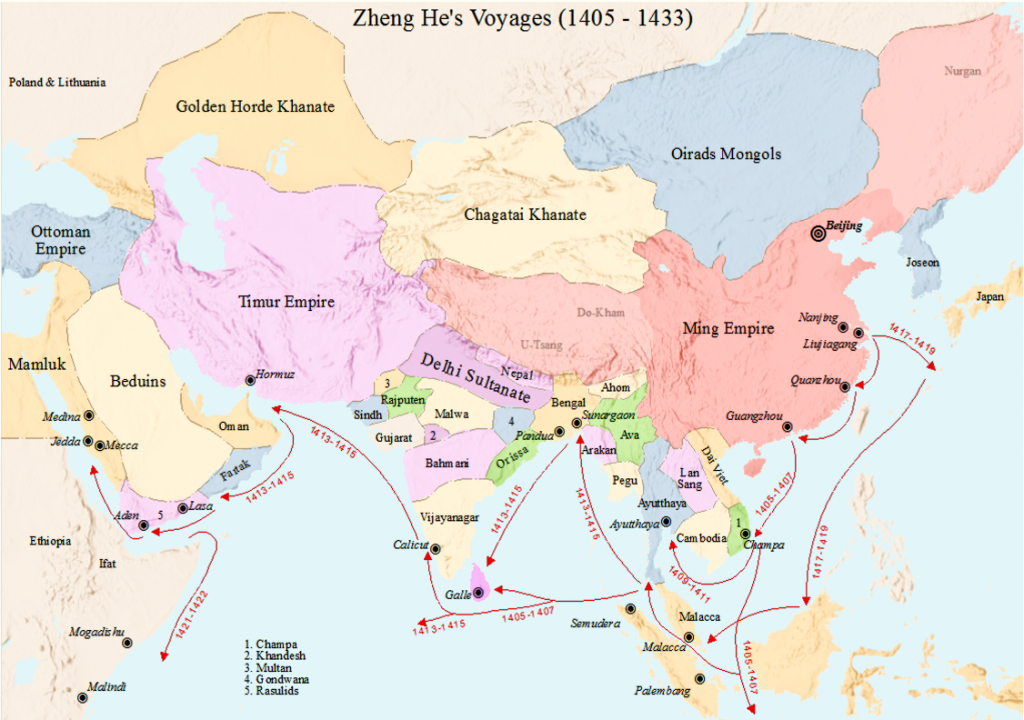

In the early 15th century CE, a new major maritime power entered the Indian Ocean. This was the Muslim-Chinese admiral Zheng He, who on the command of his boss, the Ming emperor known as Yongle, assembled a fleet of unprecedented size and from his home base in Nanjing undertook seven great voyages that took the fleet all around the Indian Ocean to East Africa.

British historian Roger Crowley wrote in his book Conquerors: How Portugal Forged the First Global Empire (p.xx) that,

The [Chinese] fleets were vast. The first, in 1405, consisted of some 250 ships carrying twenty-eight thousand men. At its center were the treasure ships: multi-decked, nine-masted junks 440 feet long with innovative watertight buoyancy compartments and immense rudders 450 feet square… The fleets carried sufficient food for a year… and navigated straight across the heart of the Indian Ocean from Malaysia to Sri Lanka, with compasses and calibrated astronomical plates carved in ebony. The treasure ships were known as star rafts, powerful enough to voyage even to the Milky Way…..

The voyages of the star rafts were nonviolent techniques for projecting the magnificence of China to the coastal states of India and East Africa. There was no attempt at military occupation, nor any hindrance to the area’s free-trade system…

In 1433, these voyages abruptly ended. The Yongle Emperor had been succeeded by another emperor less interested in maritime discovery; and with Mongol armies threatening Nanjing he apparently decided he needed to invest more heavily in land forces than in grandiose shows of maritime force.

Zheng He himself died in either 1433 or 1435. Chinese merchants continued to trade with partners in India and Southeast Asia. But over the 600 years since then there has never been any attempt to replicate his massive fleet and its always very impressive “show the flag” mission.

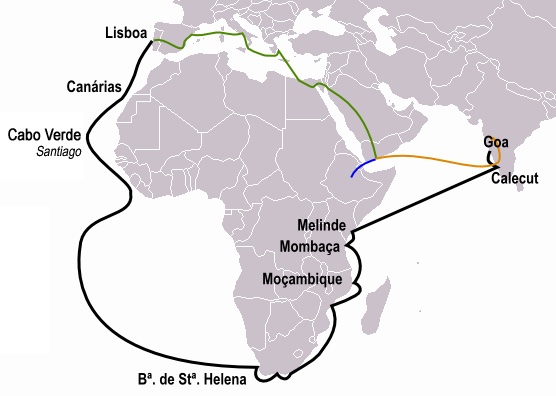

Seventy years after Zheng He’s death a radically new force entered the Indian Ocean “system”. This was a tiny fleet of four tiny (80-foot) but well-armed ships captained by the Portuguese navigator Vasco Da Gama. In 1497-98 Da Gama showed he had figured out how to use the wind patterns of the South Atlantic to reach, and then round the southern tip of Africa into the Indian Ocean. After doing that, in the spring of 1498, Da Gama used the monsoons off East Africa to bring him up to Calicut, a major trading post on the southwest coast of India.

By the time Da Gama entered the Indian Ocean, the monarchy back home that supported, financed (and profited handsomely from) his ventures had already spent more than 80 years systematically building the first transcontinental empire that modern Europeans had ever built. Starting in 1415 CE, successive Portuguese kings had regularly sent out well-armed small armadas of vessels to establish and maintain a string of heavily armed and well fortified “trading posts” ever further down the west coast of Africa.

The goal of those outposts was always to extract whatever they could from the lands they dominated—gold, minerals, precious dyes and woods, and increasingly also coffles of violently subdued and well-chained captive Africans… and to ship them back to Lisbon for the profit of the king and his fellow investors. The navigational smarts and above all the weight of the naval cannonry the Portuguese naval captains employed allowed them to overcome any spurts of resistance they might encounter from the Indigenes.

In 1495, a new, extremely messianic and Islamophobic king, Manuel I, was crowned in Portugal. Like other West Europeans, he had long heard about the riches produced in the more technologically advanced countries of the Indian Ocean rim; and he railed at the fact that all the land and sea routes connecting European with those riches were controlled by Muslims. So he reinvigorated the Portuguese empire-building project, dispatching his star sea-captain Vasco Da Gama to find a route to the Indian Ocean that could connect Portugal directly with its riches. (It soon became clear that Manuel aimed not only to smash the Muslim-dominated trade patterns but also, if he could, to destroy Islam in its Arabian Peninsula heartland.)

It was probably Da Gama who came up with the idea of using the counter-clockwise winds of the South Atlantic to get him round Southern Africa. That tactic continued to work well, for him and for the many other Portuguese empire-builders whom Manuel dispatched annually to the Indian Ocean zone, once Da Gama had demonstrated how to do this.

Roger Crowley’s book has an entire chapter on how the early Portuguese conquerors used systematic terror to impose their will on the communities they encountered around the Indian Ocean rim. I digested some of the key examples of that, here. The first example was Da Gama’s own 1502 disabling and burning-at-sea of a ship sailing along India’s Western coast that was returning from the pilgrimage to Mecca, carrying 240 men, including a number of rich merchants, as well as women and children.

On Da Gama’s orders, only twenty of the children and the ship’s pilot were allowed to be saved, with mandatory conversion to Christianity being their fate.

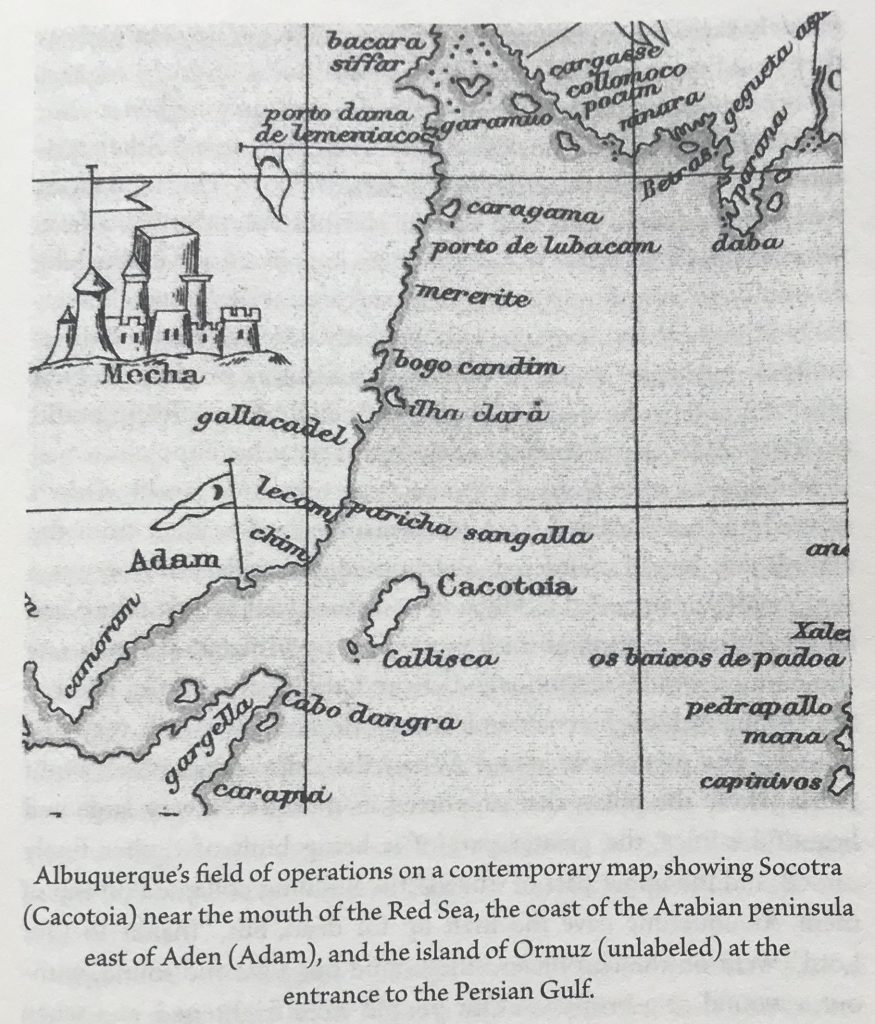

Five years later, Manuel gave another of his commanders, Afonso de Albuquerque, the mission of approaching the mouth of the Red Sea, and then “guarding” that passageway and capturing Muslim cargo ships there. But he also directed Albuquerque to travel further east along the south coast of the Arabian Peninsula and to, “establish treaties in places that seem useful. such as Zaila, Barbara, and Aden, also go to Ormuz, and to learn everything about these parts.”

Albuquerque took those orders as a license to loot, destroy, and pillage wherever he went. Crowley wrote, p.172:

Some of [these] ports along the Omani coast submitted meekly. Others resisted and were sacked. Swarms of criminalized seamen from the Lisbon jails looted, murdered, and burned. Exemplary terror was a weapon of war, intended to soften up resistance farther down the coast. In this fashion, a strong of small ports went up in flames. In each one the mosque would be routinely destroyed; the destruction of Muscat, the trading hub of the coast… was particularly savage… Albuquerque was intent on transmitting terror ahead of him: “he ordered the ears and noses of captured Muslims to be cut off, and sent them to Ormuz as a testimony to their disgrace.”

Throughout most of the rest of the 16th century, the Portuguese carried and maintained their regime of terror around the whole of the Indian Ocean rim. In 1509, a Portuguese navigator reached Malacca, in today’s Malaysia. The Muslim sultan of that strategically located area was unwelcoming. In 1511, a follow-up Portuguese expedition returned, captured the sultan’s fort, and set up a permanent Portuguese fort in its place. That fort soon started functioning as the hub of a violent Portuguese trading network that stretched around the East Indies and across the South China Sea, including to China and Japan.

At first, the Portuguese had a free hand in the Indian Ocean. No local power was able to withstand them. The only other European power that in the 16th century was capable of building and maintaining a transoceanic empire was its large, also Catholic) neighbor in the Iberian Peninsula, Spain. But at first, Spain’s imperial ambitions were focused solely westward, on the “New World”, leaving the older trading areas of the Indian Ocean free for the Portuguese to exploit.

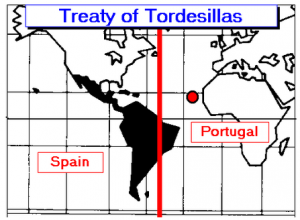

By 1492-93, Christopher Columbus had reached and reported on his North American “discoveries” to Spain’s Ferdinand and Isabella and claimed those lands in the name of Spain. In 1494, the two European powers reached the Treaty of Tordesillas which—with breathtaking arrogance—divided the whole of the non-European world between the two powers’ ambitious imperial planning.

The Spanish then spent some years pursuing extremely profitable (and brutal) projects of colonial extraction in the areas of the Caribbean, and North, Central, and South America that they very violently subjugated.

In 1518-19, an ambitious new Spanish King, Charles I, became tempted by yet another exploration project. This time, what tempted Charles was a project by a disaffected Portuguese sea-captain called Fernão de Magalhães (Ferdinand Magellan) to sail to the fabulously rich “Spice Islands” of East Asia by approaching them from the Pacific, not the Indian Ocean. Magellan had earlier sailed to Malacca with the Portuguese, so he knew his way around the seas of East Asia…

With Charles’s backing, Magellan set sail from Spain in September 1519. It took him more than two years to sail around the tip of South America and across the Pacific, reaching first Guam and then the island of Samar, located in the east of what are today the Philippine Islands, which he claimed on behalf of Spain.

Magellan was killed on the beach at Samar by local resistance forces. But other Spanish captains in his flotilla then explored other parts of the island before they brought the expedition’s remaining ships back to Spain—which they brashly did by sailing westward, along the “Portuguese” route.

The Portuguese were furious that their renegade captain had registered such a great achievement for the Spanish. But in 1525 they concluded the Treaty of Zaragoza with Spain’s Charles, which delineated a clear new division between them in the East Asian seas, that mirrored the one they already had in the Atlantic.

From then on, Spain’s imperial fortune-hunters would have a (Papally recognized!) presence in the island chain that, a few decades later they would name the Philippines.

In 1580, there was a deep political crisis in Portugal, that resulted in the country’s monarchy being taken over for the next 60 years by Spain. During that period, the Spanish monarchs, who were from the Habsburg dynasty, were focused on maintaining and where possible expanding the extensive empire they had already built in the Americas and the Philippines—and also, on continuing the seemingly never-ending task of trying to bring the rest of continental Europe under their rule.

During those years of the “Iberian Union”, Spain’s rulers did not pay much attention to the extensive, and previously profitable, network of armed trading posts that Portugal had built all around the rim of the Indian Ocean. That provided a great opening for two other European powers that also wanted to grab some of the spoils of having a worldwide empire. These were England and the Netherlands, two originally very strongly Protestant powers that (a) were not part of the Papally blessed, intra-Catholic cartel of the Treaties of Tordesillas and Zaragoza, and (b) were anyway battling Spain ferociously in Europe.

These two newcomers had already figured for a while that building out their own plundering empires in the Indian Ocean—and anywhere else they could in the non-European world—would help them amass the war-chests they’d need to resist Spain’s attempts to do regime change to them in Europe… while it could also handily cut down the amount of plunder available to Madrid.

England and Netherlands were both sea-facing and very sea-focused polities, able to command seasoned and capable naval fighting forces and to raise money for their far-flung imperial ventures through the new-fangled mechanism of of the stock-market, that arose in both polities at around that same time, too. From the beginning of the 17th century on they raced with gusto into the Indian Ocean and other parts of the non-European world, battling against Spain, Spanish-controlled Portugal, and very frequently each other as each of them sought to build a brutally extractive empire for the benefit of the shareholders in its own stock markets.

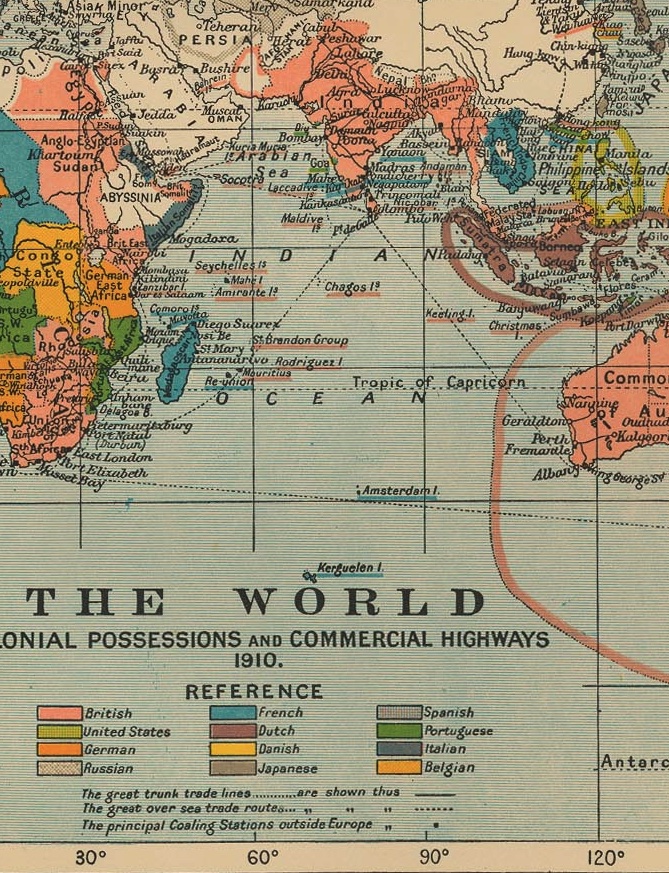

Around the Indian Ocean, during the early decades of the 17th century England and Netherlands were able to capture most of armed trading posts that Portugal had established there, as the Spanish kings who now headed the Iberian Union kept their focus elsewhere.

I’m going to fast-forward nearly 300 years here. We know that in the Indian Ocean arena, by the early 20th century the Dutch ended up controlling the islands that would become Indonesia, and the Cape of Good Hope. Meanwhile, the English (now “British”) controlled India, Malaysia, Burma, Sri Lanka, Australia, large chunks of East Africa and the Arabian Peninsula, and several strategically located islands and island-chains; relative newcomer France controlled Madagascar, Indochina, and some strategically located islands; and the even newer arrivals to the empire-building scene Germany, Italy, and the United States also had several possessions (for the United States, that was the Philippines.) Portugal’s remaining holdings in this arena were limited to Mozambique and tiny East Timor.

I grew up in England during the time of the retreat/collapse of the once-powerful British Empire. London had given (or India had seized) its independence in 1947. In 1956, just before I entered kindergarten, Prime Minister Anthony Eden joined France and Israel in the ill-fated Tripartite Aggression against Egypt that led to Pres. Eisenhower forcing the three aggressors into a humiliating retreat. (For England, he did that by economic pressure: he threatened to pull the plug on U.S. support for the pound sterling.) Over the years that followed, most of the peoples of London’s colonial possessions in Asia and Africa one by one gained their political independence.

By 1966, Britain’s only remaining military bases around the Indian Ocean were in Aden and Singapore. That year, the government announced it would withdraw from those “East of Suez” bases by the mid-1970s. In 1967, amid further global pressure on the pound sterling, the timetable was accelerated, with the deadline brought forward to 1971.

Oxford University’s Dr. William D. James wrote in 2021 that,

Enthusiasm in Whitehall for retaining major bases East of Suez declined during the 1960s as it dawned on policymakers that these installations were no longer springboards for power projection but had instead become resource-consuming quagmires. As [Defence Secretary Dennis] Healey explained: “to seek to maintain military facilities in an independent country against its will can mean tying down so many troops in protecting one’s base that one has none left to use from it. The base then becomes a heavy commitment in itself and loses all its military value.”

One of the consequences of this British withdrawal was that all the remaining British possessions and protectorates on the Arabian Peninsula had speedily to be established as independent states. Saudi Arabia itself, easily the largest polity on the peninsula, had been recognized as independent (with the support of the United States) since 1932. Kuwait had been given independence in 1961. The nationalist movement in South Yemen (Aden) won its independence from Britain in 1967.

So as Britain withdrew from “East of Suez” in 1971, the remaining independence challenges related to the string of British protectorates that ran down the Arab coast of the Persian Gulf, which the British had called the “Trucial States.” Of these, Bahrain and Qatar emerged as independent states in Fall 1971. The other seven, much smaller Trucial States agreed to join a confederation called the United Arab Emirates, of which Abu Dhabi and Dubai were the most powerful.

Since the 1971 withdrawal of Britain from the Arabian Peninsula and the rest of the Indian Ocean arena, the United States has been far the most potent Western military power there, with military bases ringing the ocean and also stationed smack in its midst in Diego Garcia (the Chagos Islands.) But what services do these bases perform for the residents of the countries that ring the Indian Ocean? Do they help keep them safe—or do they, by their very presence keep global and regional tensions high, inhibit the free flow of trade, and impose other high costs on the peoples of Indian Ocean rim? I’ll be exploring these questions more in future essays.