Above: Pres. Putin poses with some of the African leaders who attended the Russia-African summit he hosted this past week

Biden administration officials and their supporters have long claimed that the conflict in Ukraine is a clear-cut contest between “democracy” and “authoritarianism” that affects the whole world… and that on that basis the countries of the Global South should line up to support NATO’s campaign against Russia. One big recent version of this argument has been the claim that Russia’s refusal to renew the agreement allowing Ukraine to export grain via the Black Sea is raising grain prices and preventing much-needed foodstuffs from reaching hunger-struck countries in Africa…

But the campaign to win global support for NATO’s anti-Russia crusade has never been very successful. Recall that in the three votes Washington initiated at the UN last year to denounce Russia’s actions inside Ukraine (e.g., 1, 2), three dozen countries including global behemoths China, India, and three dozen other countries failed to support the “Yes” vote.

And just this past week, the proceedings of key gatherings held in South Africa and Moscow have underscored the extent to which the “West” has lost the support of that large majority of humanity that lives in the formerly colonized countries of the Global South. (If indeed, it ever had it… Perhaps a better description of what’s been happening in recent months is that the West is now revealing itself as incapable of imposing its will on the countries of the Global South. More on this, later…)

So what happened at these two recent gatherings?

In Johannesburg, South Africa, a high-ranking Russian official joined with national-security leaders from the four other “BRICS” countries—Brazil, India, China, and South Africa—to push forward plans that the BRICS summit slated for late August will transform BRICS into an organization that (a) will likely add adds some international governance issues to its longstanding economic/financial agenda, and (b) may add more than 20 new countries from the Global South to its current membership roster of five.

And in Moscow, meanwhile, Pres. Putin—and also, surprisingly, his ever-mercurial frenemy, Yevgeny Prigozhin—welcomed the presidents of South Africa, Egypt, and 15 other African countries to a Russia-Africa summit at which Putin (a) challenged some of the more alarmist claims Western leaders have made about the impact of the ending of the Black Sea deal, and (b) undertook to donate tens of thousands of Russian grain to needy African countries.

There is, indeed, some merit to Putin’s argument that Western warnings of sky-high grain prices are overblown. The screengrab I took today from Business Insider of the 3-year trajectory of global wheat prices shows current prices not yet coming close to reaching those recorded in late 2021.

(Recently, a couple of presumably well-meaning Western commentators had argued that the food -price crisis is so dire that NATO should organize either a Berlin-style airlift or a sealift to try to get Ukrainian grains to world markets. I wrote about the highly escalatory—and actually unnecessary—nature of those proposals, here.)

Anyway, I have a proposal of my own. How about we trust Presidents Ramaphosa and Sisi and the other African heads of state and government who were recently in Moscow to chart the best diplomatic course(s) for their countries in light of their own experience, rather than having Western leaders tell them what to do?

BRICS: Its history and its future

Much more momentous than the recent Russia-Africa summit, however, is the ongoing evolution and growth of the BRICS group. BRICS was inaugurated (at Russia’s initiative) in 2009, as a reaction to two developments: the global financial crisis of 2008, and the decision the big Western nations took that year—in response to Russia’s actions in Ukraine—to expel Russia from what had previously been the “G8” economic grouping. (Leaving it as the G7.)

With the birth of what was initially called the “BRIC”, Russia and China joined with India and Brazil to start building an alternative to the many West-dominated institutions that sit at the apex of global economic decisionmaking: not just the G7, but also the World Bank, the IMF, the “SWIFT” payments system, and so on… A year later, they brought in South Africa, making it the BRICS.

It has stayed at five members until now, and along the way established the New Development Bank, which is now headed by former Brazilian president Dilma Roussef.

For the first dozen years of BRICS’s history, its leaders stuck with their initial, nearly exclusively economic focus for its work. And for good reason. Should “politics” rear its ugly head within BRICS, there were always potential conflicts that might erupt between China and India. (The armed forces of those two countries—both of which also have nuclear weapons—have engaged in a lengthy though intermittent series of low-level border clashes, the most recent of which may have occurred last December. )

Also, until recently, all the members of the BRICS had retained deep economic ties to Western countries, even while they sought some means of escaping or easing Western domination. So all of them remained quite reluctant to do anything to openly confront the Western world system.

Plus of course, so long as close Trump buddy Jair Bolsonaro was president of Brazil, it was very unlikely that BRICS as a whole would ever do anything serious to buck Western influence…

However, over the past few years (as I also wrote here) a number of those factors started to change. Most notably, last year Bolsonaro was defeated at the polls by Lula Da Silva, a man with a long commitment to building the capabilities of the Global South.

Other factors have also been pushing the BRICS countries towards taking a broader, possibly even somewhat “political”, path:

- Throughout the Covid pandemic, people throughout the Global South saw the extreme selfishness with which Western nations refused to share with pharmaceutical producers in India, South Africa, and elsewhere the “patents” with which the (heavily government-funded) Western corporations guarded the secrets of their proprietary Covid vaccines.

- They noted the hypocrisy of Western leaders who called for war-crimes trials for President Putin while steadfastly refusing to bring the authors of the (quite illegal) 2003 invasion of Iraq to any form of account.

- From early 2021 on, China’s leaders saw that the strongly anti-China policies initiated by Pres. Donald would be kept in place by Pres. Biden—and Biden then also added in many anti-China measures of his own.

- At a broader level, too, millions of people in the Global South had long railed against the harmful economic sanctions that Washington, or Washington+Brussels, had imposed against either their countries, or neighbors. Over the year, many members of “Team Sanctioned” had started trying to build workarounds to the West-imposed restrictions. In February 2022, when Washington and its allies slapped punishing sanctions on Russia, that threw all of Russia’s non-trivial economic heft into the arms of “Team Sanctioned”, considerably increasing its counter-West capabilities.

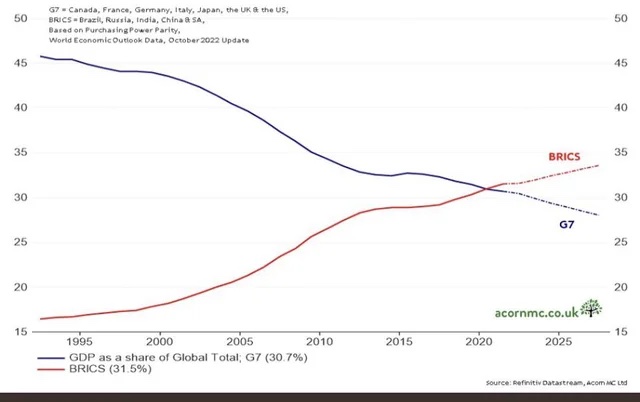

Along the way, in 2021 the GDP of the five BRICS members, in “PPP” terms, came to exceed that of the G7. (See chart.)

Plus, over recent years China’s patient economic and diplomatic engagement with countries around the world has started to erode the West’s sway in large parts of Africa, West Asia (the “Middle East”), Southeast Asia, and even Latin America over which Washington or its allies previously exercised an almost effortless hegemony. Beijing’s ability to work completely under Western radar to bring about last March’s reconciliation between Saudi Arabia and Iran was a set-piece of that diplomacy.

Small wonder, then, that in recent months increasing numbers of leaders from throughout the Global South have been lining up with requests to join BRICS.

Back in June, BRICS foreign ministers held a meeting in Cape Town to prepare for the upcoming BRICS summit, which is slated to be held in South Africa in late August. In parallel with that meeting, the BRICS ministers held a session with counterparts from a group called “Friends of BRICS”—presumably, a group of countries they were considering inviting to include in their membership. That group included (in-person and virtually) ministers from the following countries: Iran, Saudi Arabia, UAE, Cuba, Democratic Republic of Congo, Comoros, Gabon, Kazakhstan, Egypt, Argentina, Bangladesh, Guinea-Bissau, and Indonesia.

This past week, BRICS held another preparatory meeting in South Africa, once again with many of those same “Friends” invited. This time, significantly, the lineup of attendees and the broadcast remarks that South African Minister Khumbudzo Ntshavheni made at the beginning of the Friends meeting indicated that some broadly political issues could also be on the table in August.

Among the attendees this week were: China’s topmost foreign-affairs honcho, Foreign Minister Wang Yi, Indian National Security Advisor Ajit Doval, and key Brazilian strategist Celso Amorim. (Wang’s attendance was notable as it came at the same time that the disappearance of his short-lived predecessor as FM, Qin Gang, had been confirmed as a complete demotion for Qin. Wang later traveled from South Africa to Kenya, Ethiopia, and NATO member Türkiye, indicating a desire to be very hands-on as he resumed the FM role he had previously held from 2013 until last December.)

As for Minister Ntshavheni’s welcoming remarks, she said:

We host this meeting when the geopolitics pertaining to our world have taken center stage and are affecting and impacting on the development of all and of national interest to all. But this is the time for us to seek resilience and extend friendship to our people… There are both new and old challenges that are confronting BRICS, but they all grant us an opportunity to create an environment and a world order that reinforces mutual benefit and global development that is inclusive…

The commentary on this week’s meeting that came from China’s semi-official China Daily seemed somewhat more cautious. It stated only that, “It is to be hoped that the upcoming summit will further contribute to building a fairer and more open global development architecture to the benefit of all developing nations.”

The CD commentary did also include two intriguing tidbits. First, though France’s Pres. Emmanuel Macron had asked if he could attend the August summit, CD reported that his request had been turned down “because of opposition from Russia.” (Relevant to that is that, under Western pressure, the South African government earlier said it would not be inviting Pres. Putin to attend the summit in person, though he could take part virtually and would be represented in person by Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov.)

The CD report added this commentary:

[T]he fact that the French leader sought an invitation to attend the summit reflects the growing stature of BRICS.

That explains why so many developing countries are seeking to join the group. So far more than 40 countries including Saudi Arabia, Indonesia and Iran have expressed an interest in joining, with 22 of them having already formally applied to do so.

Secondly, CD also noted that Pres. Ramaphosa has invited the heads of state of all the African countries to attend the August summit. It quoted him as saying,”Our continent was pillaged and ravaged and exploited by other continents and we therefore want to build the solidarity in BRICS to advance the interests … of the continent as a whole.”

BRICS and other upcoming international gatherings

The BRICS summit in Gauteng, South Africa, August 22-24, will be the first in a string of momentous international meetings over the months that follow; and by being the first it can certainly help to shape the outcome for the others.

After the BRICS summiteers wrap up in Gauteng, many of them will then be heading to:

- The G20 summit, due to be held September 9-10 in New Delhi. The G20 is a kind of “bridge” grouping primarily focused on economic affairs that brings together, on the one side, the members of the G7 along with Australia and a couple of other very pro-Western states; and on the other, the five original BRICS states, and a few other economic heavy-hitters from the Global South like Argentina, Mexico, Indonesia, Türkiye, and Saudi Arabia. It’s worth noting that most of the non-G7 members of the G20 are also members of the “Friends of BRICS”.

- The UN General Assembly, due to be held in New York City, September through December. This year’s General Assembly meeting will include a specially themed “SDG Summit”, September 18-19, at which national leaders will review the progress the world has made to meeting the “Sustainable Development Goals” the United Nations adopted back in 2015. The target date the U.N. designated back then for achieving the 17 stated goals was 2030. So this year’s “SDG Summit” will be, effectively, a half-way progress report.

- The Annual Meetings of the World Bank and the IMF, to be held in Marrakech, Morocco, October 9-15. These bodies, which were established by Washington at the end World War II, have a lot of weight in the governance of global economic affairs. In the decisionmaking of the World Bank, the U.S. vote counts for 15.74% of the total (per the PDF here), while that of all five BRICS countries counts for 14.24%. The votes of the five non-US members of the G7 add up to 23.55%.

- The 28th Conference of Parties to the Paris Climate Treaty, to be held November 30 – December 12 in Dubai, UAE. I don’t have much to add here about “COP28” as it is known. I wrote a bunch here and here last week that compared the records of the United States and China on issues related to the ongoing climate crisis. I will just express the hope that in Dubai, as at the SDG Summit in September, participants don’t descend into finger-pointing and accusations but rather they look for strong records and best practices on these literally existential issues, and work together to craft and commit to the constructive that our children and grandchildren all so desperately need.

But first, let’s see what can be achieved at the BRICS meeting in late August…

Helena, thank you for your dedication & skill at gathering the issues on the big stage & analyzing the alliances of these many groupings of nations. Your insight helps greatly with recognizing the diminishing influence of the US & “the West” on the world stage, and our dire need to take the blinders off. It actually gives me hope.

I’m so glad you’re returning to focus on your writing- we sorely need your perspective – and hope a publisher for yr book co. steps forward for a smooth transition. Much appreciation for you & your work!!!

Sally Campbell

http://www.sallycampbellmediator.ca

The remarks of the minister from South Africa jump out at me: “…an opportunity to create an environment and a world order that reinforces mutual benefit and global development that is inclusive…” This is the theme announced by Xi Jinping and Vladimir Putin in Beijing last year.

To recap, the Russians and Chinese announced a joint project for mutual security and wellbeing among the project participants. They have extended an invitation to all countries to join them in putting aside ancient suspicions and tribal priorities. The project appears alive in the Middle East where Iran and Saudi Arabia have recently found common ground with Chinese help.

Take a close look at the faces of the people with Vladimir Putin in the lead photograph in the blog post. It may be a lot to read into some smiles, but I think the people in the photograph are happy with the direction of the current on which they ride.

Thank you for this broad analysis of global politics today.