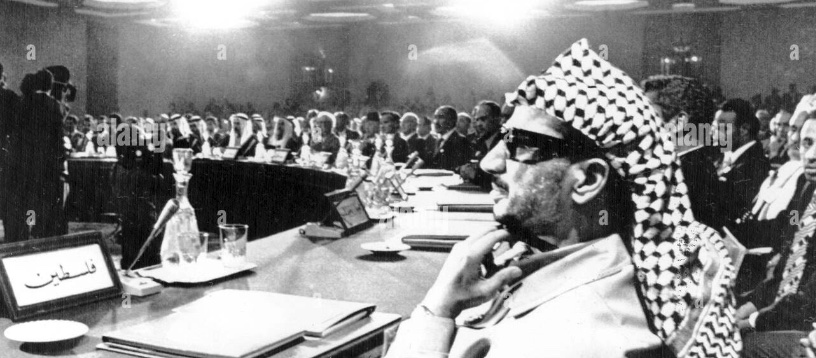

PLO leader Yasser Arafat taking part in the November 1974 Arab League summit

Most of the current commentary in the Western media on the 1973 Arab-Israeli war has focused on the “shock” effect the war had on Israel’s society and politics, or on the role the war played in jump-starting the Egyptian-Israeli negotiations that in 1978 led to the Camp David Accords, and a year later to the conclusion of a complete Egyptian-Israeli peace. (The recent release of a new Hollywood movie about Israel’s then-premier Golda Meir has helped keep the focus on the Israeli dimension of the war, though the historical accuracy of the movie has come under much serious questioning, e.g. here, here, or here.)

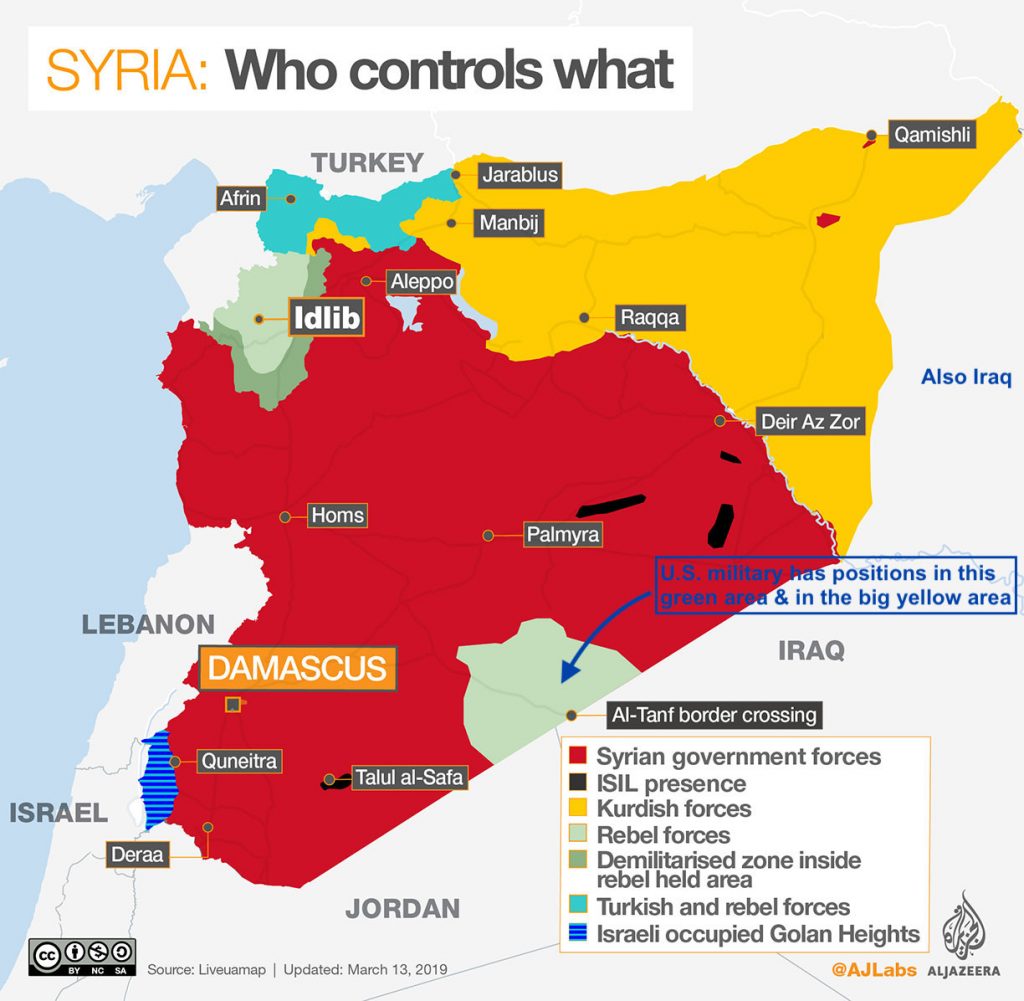

However, the Israelis and Egyptians were far from the only peoples in West Asia (the “Middle East”) whose fate was greatly impacted by the war. Indeed, given that Egypt was at that time far and away the weightiest of the Arab states, the fact that the war led to the launching of a diplomatic process that removed Egypt from the coalition of Arab parties that since 1948 had been in a state of unresolved war with Israel transformed the balance of power throughout the whole region.

The parties most direly affected by Egypt’s removal from the former Arab-rights coalition were firstly the always vulnerable Palestinians, and also the states of Syria (which had been a party to the war of 1973) and Lebanon, which had not.

Continue reading “The 1973 Arab-Israeli war and the Palestinians”