Photo from a CodePink rally

I’ve been mulling for a while over why the U.S. peace movement these days skews so geriatric. No ageist bias is intended here: I myself am 70 years old. (Also, I intend no commentary on the ages of the fabulous CodePink activists in the photo above, which I included here mainly for inspiration!)

But really, if we want the antiwar movement to continue and to grow over the years ahead, rather than dying out with all of us Medicare recipients, then surely we need to do more to address the challenge of intergenerational renewal?

I have come up with a preliminary list of reasons for the conundrum of the relatively low interest the younger generations show in joining the peace movement, which I’ll share in just a minute. And I’ll share some preliminary ideas on what we might do to revive the movement. But I also want to note that there is lots of interesting data relevant to this issue that’s available from large organizations that have the capacity to conduct large, nationwide polls on a variety of issues. So I’ll be sharing some of that data here, too.

First, though, here’s my preliminary list of seven reasons, based mainly on anecdotal evidence including from conversations with my own children (born between 1978 and 1985) and other people of their age and younger:

- There is no general conscription here in the United States. (In general, this is excellent, though it does mean that the ranks of our massive military are filled largely through economic conscription.)

2. Americans who came of age after about 1990 have no vivid experience of facing the threat of nuclear war. This is true of my own children and also of nearly everyone in the cohorts that demographers call “Generation X” (born 1965-1980), “Millennials” (born 1981-96), and “Gen Z/ Zoomers” (1997-2012). Again, not having faced a threat of nuclear war is generally a good thing. But…

3. In good part as a result of that, members of those younger age cohorts have never really had to have a strong understanding of the omnicidal realities of the nuclear-weapons age. Many have also become used to living in an era of unquestioned U.S. dominance of the world arena and to the idea that it is somehow the responsibility of Americans to regulate and police the global order. (A touch of “White Man’s Burden” can easily creep in here.)

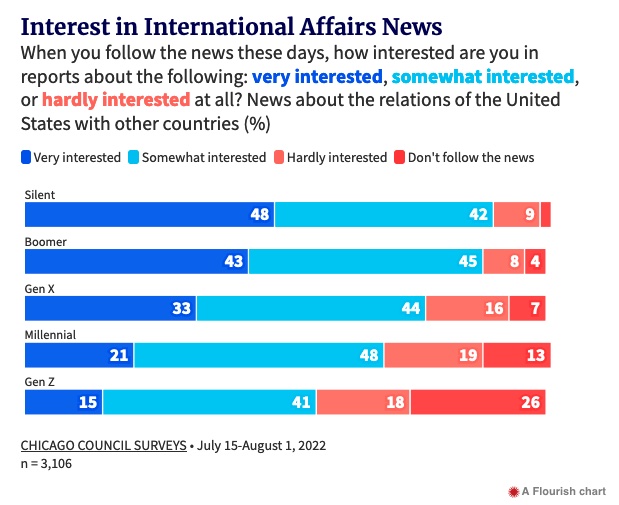

4. Related to factors 1 and 2 above, members of these three generations show markedly less interest in even reading the news about international affairs than members of the two older age-cohorts tracked in this poll from the Chicago Council on Global Affairs.

5. Members of the three younger cohorts seem to be much more concerned with issues of domestic policy, including social justice issues, gun violence, and the climate crisis, than they are with foreign-policy issues. But the climate crisis is, of course, quintessentially also a global issue! I’ll come back to that later.

6. Since the 1990s, the leading actors in the military-industrial complex have maintained a strong, and disquietingly successful, campaign to rebrand warmaking as somehow “humanitarian”. This rebranding started with the military actions (“interventions”) mounted by NATO during the post-Yugoslavia breakups, and then resumed with even greater force during the more recent crises in Libya and Syria. The arms transfers and other massive aid that NATO has provided to Ukraine can be seen as, to some extent, a continuation of this “war as humanitarianism” tradition.

7. Meantime, nearly all the U.S. corporate media, which have many close ties to the military-industrial complex, have maintained lengthy campaigns to demonize potential enemies such as (back in the day) Iraq under Saddam Hussein, and more recently Russia under Pres. Putin, and China under Pres. Xi. It’s worth underlining that Americans who think of themselves as well-educated and politically liberal have been subjected intensively to such campaigns via platforms like The New York Times and MSNBC that present themselves on U.S. domestic issues as generally liberal. Back in 2002-03, the NYT’s strong anti-Saddam bias did little or nothing to prevent the strong movement that arose to oppose the invasion of Iraq. But once the invasion had started, that movement collapsed. (Maybe related to Factor 1 above, and a widespread feeling of upper-middle-class guilt that concluded that, “We aren’t subject to the draft so maybe the least we can do is to support the U.S. troops who are subject to the economic draft.”) To be honest, it has never really recovered since then.

Some helpful data on the attitudes of “younger” Americans

The most useful survey data I’ve found that plumbs this issue of how Americans born after 1965 think about international affairs comes from two organizations:

- The Pew Research Center, a non-profit whose website states that it is, “is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. We conduct public opinion polling, demographic research, content analysis and other data-driven social science research. We do not take policy positions.” Pew has conducted wide-ranging opinion surveys spanning numerous countries and numerous issues, for many years now. Its board is composed of high-ranking academics, social scientists, and media leaders. In 2019, Pew pioneered the method of using online “knowledge panels” of pollees to largely replace traditional polling methods of calling prospective pollees by phone.

- The Chicago Council on Global Affairs, which is probably the largest of the many “regional” bodies in the United States that present programs on international affairs to local community members who typically pay a small annual membership. Chicago is a hub of U.S. agricultural exports, finance, and manufacturing. CCGA has been headed for some years by Ivo Daalder, who was U.S. Ambassador to NATO under Pres. Obama. Its board skews heavily toward leaders of banking, investment, and manufacturing companies.

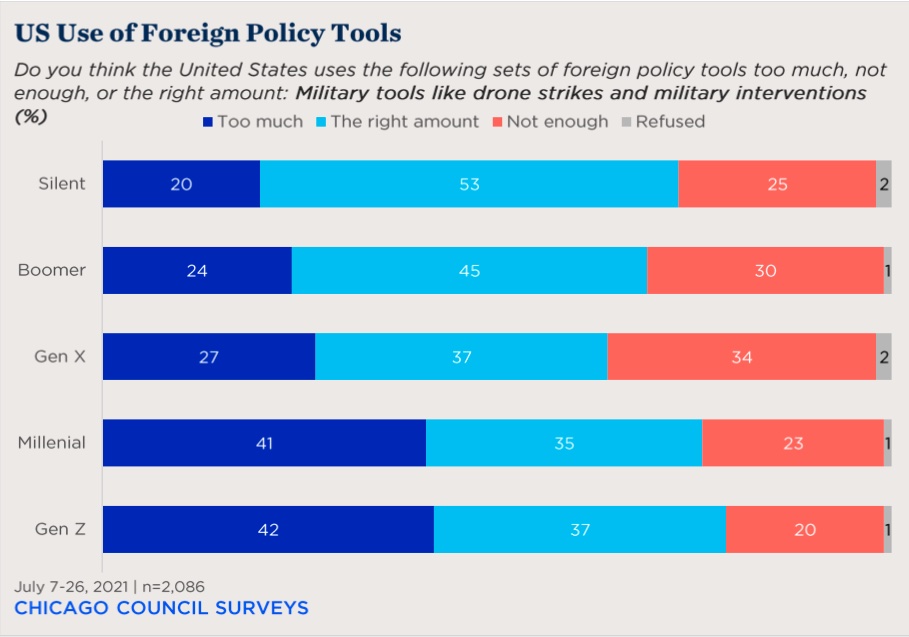

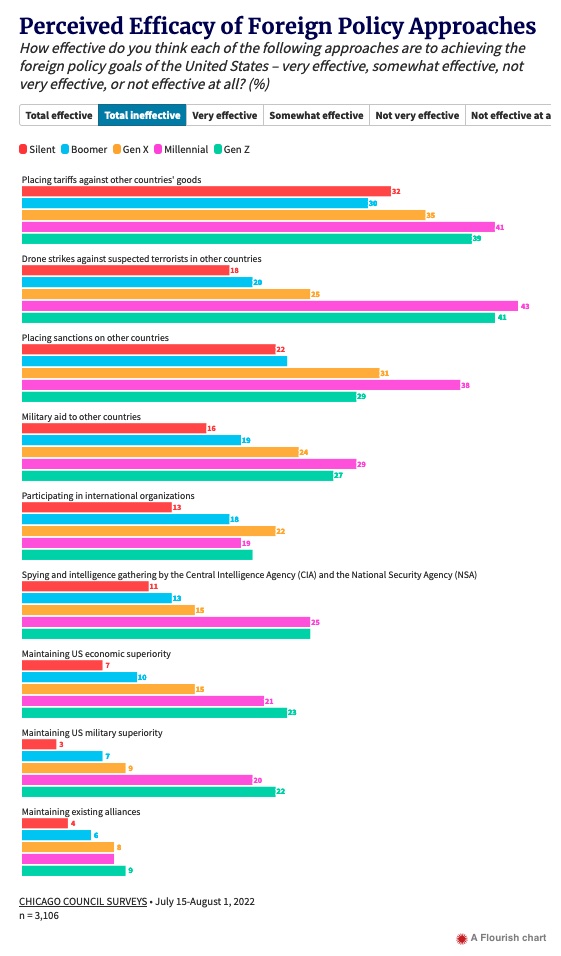

I’ll jump first into some of the data from two opinion surveys the CCGA conducted in July 2021 and July 2022. This result, from a July 2021 (that is, pre-Ukraine crisis) survey on support for use of military “tools” in conducting foreign policy, is interesting:

Those results indicate that that while the older generations, through Gen X, trended net-hawkish (more red than dark blue there), millennials and Gen Z-ers clearly reversed those preferences.

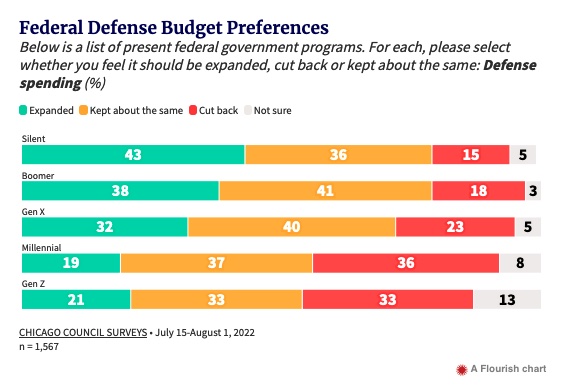

Something like those generational preferences persisted into the CCGA’s July 2022 survey, which looked specifically into the attitudes of the different age-cohorts toward U.S. military spending. Here, the question was a little different:

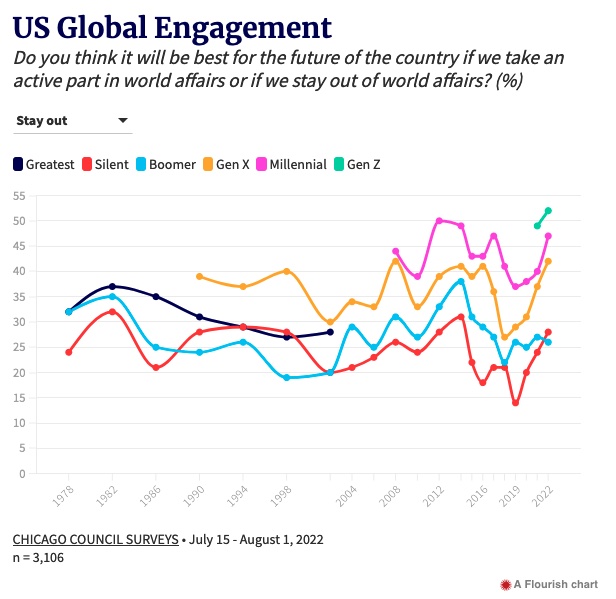

CCGA’s July 2022 survey, which was taken five months after the Ukraine conflict erupted, indicated an intriguing, pretty broad, cross-generational increase in support for “staying out” of world affairs, with the numbers notably higher among the younger generations:

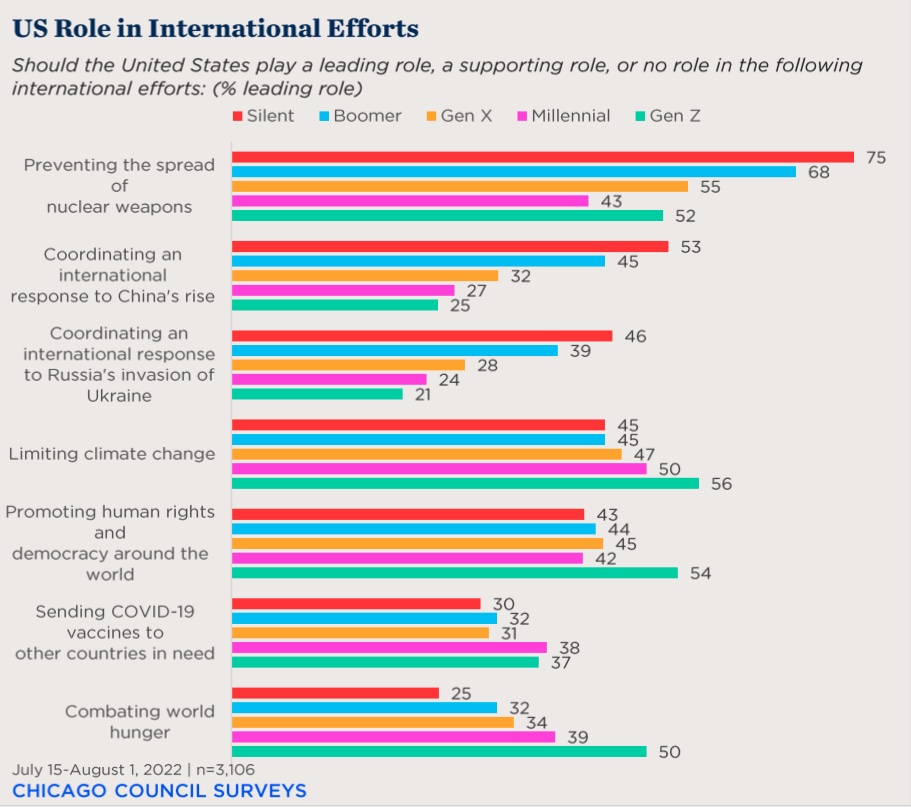

That survey also asked the 3,106 respondents which global issues, from a proffered list of seven, they wanted the U.S. to be active in, and here was how the various age-cohorts broke out on the issues on which they wanted the U.S. to play “a leading role”:

There, the relatively much stronger support from Gens X-Z for policies like “Limiting climate change” and “Combating world hunger” than for “Coordinating international responses” to the challenges from both China and Russia is very notable — and this delta is even greater for the younger of those demographics.

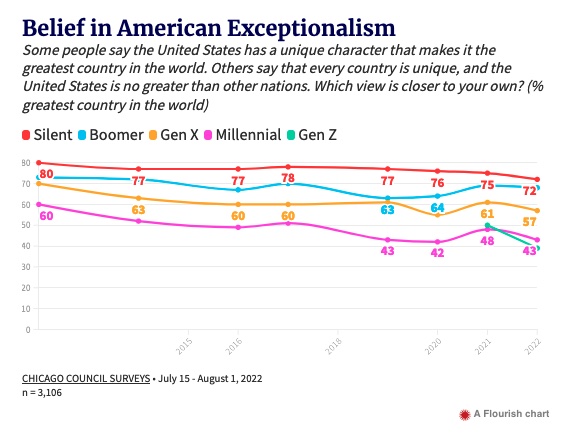

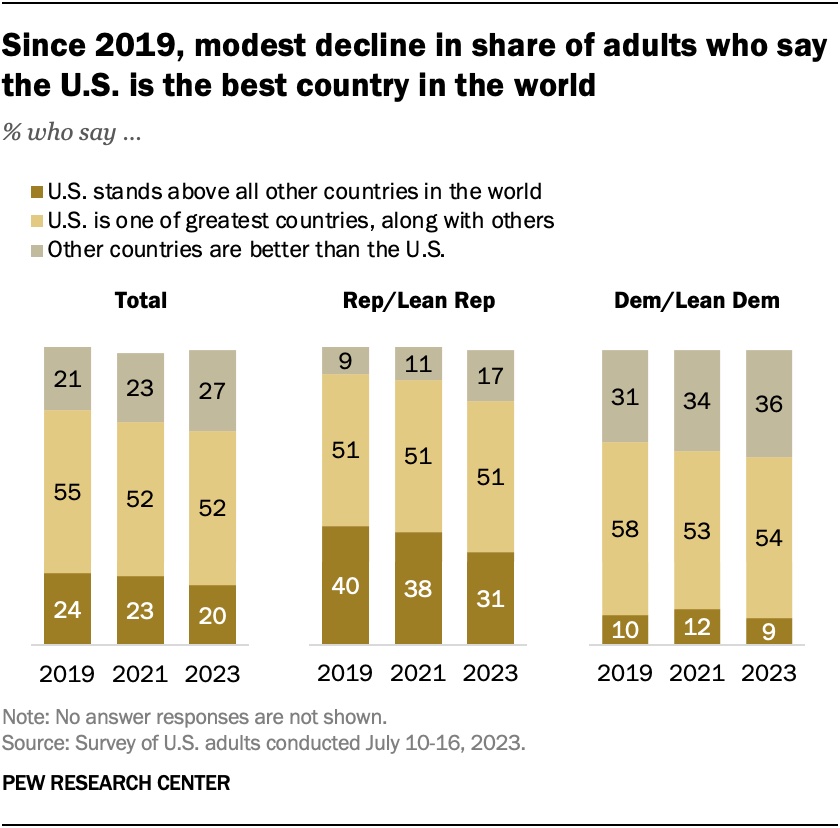

Both the CCGA and Pew have recently run polls asking about pollees’ views on American exceptionalism. Their questions were slightly different. They broke down the results they got differently, and the results they presented were very different:

However, the net result in both cases was roughly the same. Both organizations reported a net decrease in belief in American exceptionalism in recent years. The CCGA poll, by breaking out the age cohorts, showed Gen Z’s belief in exceptionalism as the lowest of any age cohort in 2022. The Pew poll on this question, which was administered in July this year, shows an encouragingly low level of support for outright exceptionalism (“U.S. stands above all other countries in the world”, as opposed to “U.S. is one of the greatest countries… “)

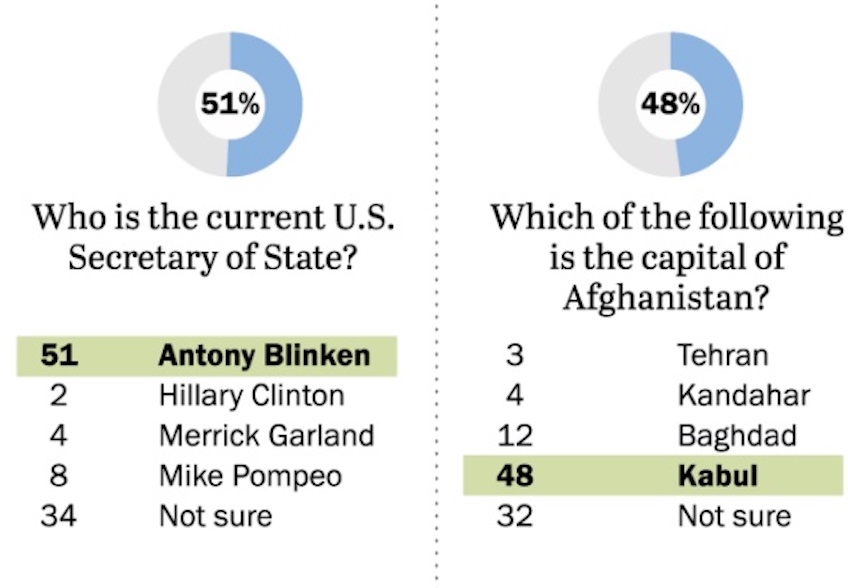

In late March 2022, one month after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Pew had administered an intriguing poll on “What do Americans know about international affairs?” The poll asked its 3,581 respondents to choose between five proffered answers to twelve straightforward “identification” questions, as shown. (One of the answers was always “Not sure.” Pew noted that this answer was chosen by many more women than men, and that men were more likely than women to choose wrong answers… )

The results of this poll provide a reality check for all of us who follow international news very closely. Only 51% of respondents could correctly name the U.S. Secretary of State. Only 48% identified the capital of Afghanistan and just 17% named the province of China with the greatest concentration of Muslims….

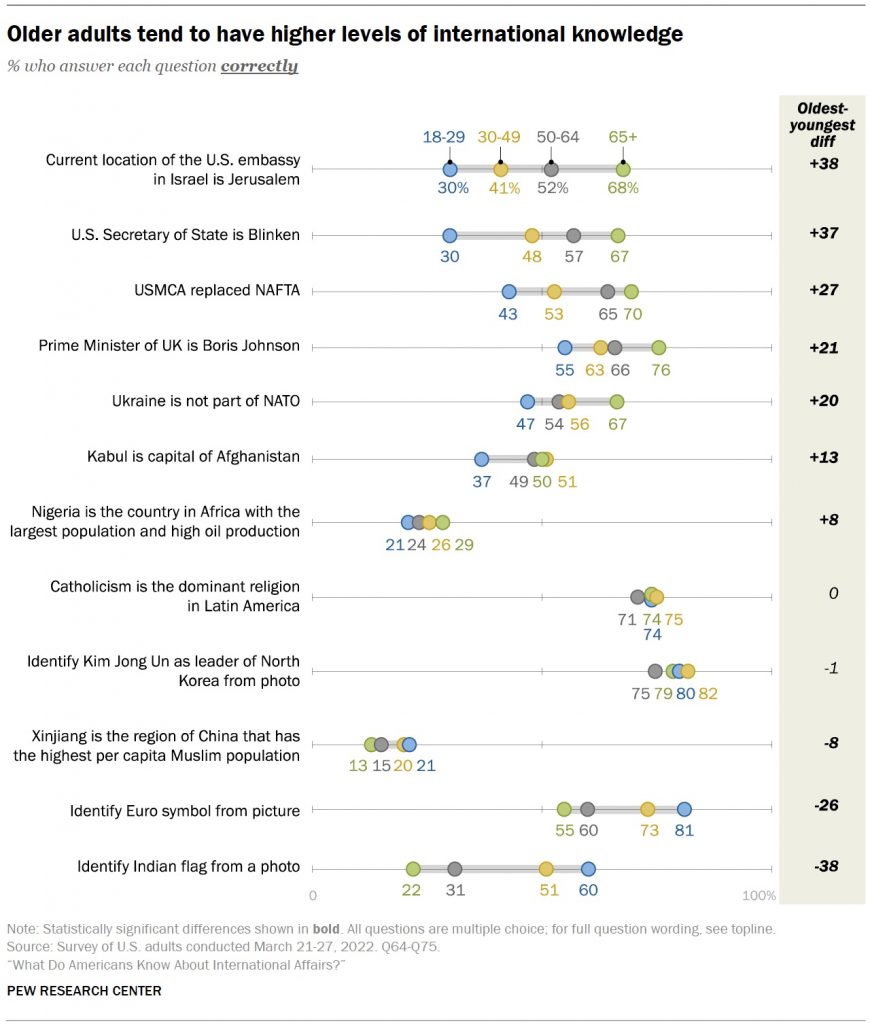

Pew also did an age breakout on these results, which produced this picture:

Anyway, a lot of the rest of that poll report is worth reading….

Some concerns about these polls and the big orgs that run them

Although I’m a big data nerd and feel I’ve learned many useful things from my foray into these big U.S. poll reports, I do just note that polling of individual respondents can in many cases be a problematic way to gauge attitudes—as opposed to, for example, organizing a robust debate on a topic and then asking for a show of hands afterwards, or any one of a number of other more community-oriented mechanisms… Also, the issue of “push-polling” needs always to be considered. It is not always as clear as asking something like, “How concerned are you about the gross corruption of Politician X?” (Respondent might then think: “Oh, is X so corrupt? I didn’t really know that. But of course if he is, as this evidently well-informed pollster seems to suggest, then of course I am very concerned about it… “)

The longer I spent reading recent CCGA and Pew polling reports, the more concerned I became about the push-polling that CCGA seemed to be engaging in.

For example, in the generationally focused poll that CCGA conducted in July 2022, they presented some very interesting (and actually hopeful!) data in a number of their charts, like the “Perceived [in]efficacy of foreign policy approaches” one shown here… But if you look more closely at the nine different options offered, eight of them are about either maintaining U.S. supremacy or implementing coercive measures, while only one—”Participating in international organizations”— has any cooperative or potentially diplomatic content to it. (Plus, military alliances like NATO or AUKUS can be considered “international organizations.”) Hence, the universe of choices that the pollsters suggest that they and their respondents all dwell in is one that is very heavily skewed toward coercion and away from seeking cooperative, respectful ways to address global challenges.

In that poll, the CCGA pollsters also asked respondents to assess a list of “possible threats to the vital interests of the United States.” The clear message: Be afraid! Be very afraid! No parallel question was posed to pollees to elicit their views on the opportunities for cooperation they might identify with various countries around the world…

Elsewhere, the CCGA poll asked respondents about how they want the United States to respond to “the situation involving Russia and Ukraine.” The five options they offered were:

- Sending US troops to help the Ukrainian government defend itself against Russia

- Increasing economic and diplomatic sanctions on Russia

- Sending additional arms and military supplies to the Ukrainian government

- Providing economic assistance to Ukraine

- Accepting Ukrainian refugees into the United States

Notably absent from the list? Any option to “Push for a speedy ceasefire in Ukraine and a resolution of outstanding issues through negotiation”, to “Seek urgent mediation from the United Nations, the OSCE, or other bodies in order to defuse the crisis”, or similar…

To me, the CCGA’s design of much of its polling effort reveals a worrying degree of pro-militaristic bias—much more so than in the Pew polling. This doesn’t render the CCGA’s poll reports worthless. Some of the most valuable aspects of what they present are (as for Pew) their time series’s, and the granularity of their attempt to break out generational differences. But the pro-militarist bias of much of their work is worth keeping in mind.

(Re-)connecting the peace movement with more younger Americans

In light of the above, I would propose a multi-faceted plan that aims to meet members of Generations X through Z—and even Gen Alpha, young people born since 2013—where they are. And that, for the people among them inclined to be activists would seem to be in the spaces around these issues:

- the climate crisis

- gun violence

- racial justice

- growing economic inequities.

Of these issues, the climate crisis is the one that, it seems to me, has the greatest number of evident connections with the goals and methods of any peace movement. Firstly, since it is clearly a global and already-present crisis, it urgently requires cooperative global action if is to be addressed with any hope of success; and the continuation of active wars and conflicts blocks any chance of such action.

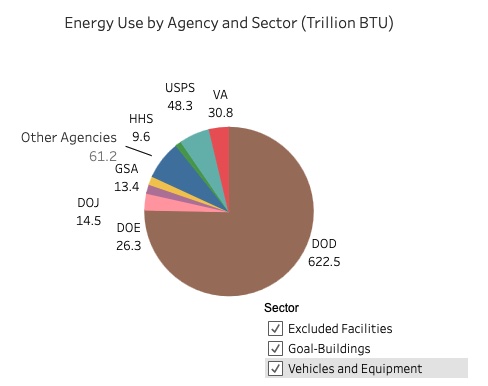

Second,the preparing and waging of war are truly gas-guzzling, high-emitting enterprises. The U.S. Department of Energy presents lots of data on this web-portal about both the energy use of different U.S. government agencies, and their levels of emissions. Here are the data for 2022 on fuel used by various agencies:

The Department of Defense, by using 622.5 TBTU in 2022, accounted for roughly 75% of total energy use by federal government agencies. (Other agencies, including the VA and the DOE itself should have some of their usage assigned to the broader “military” basket, too.)

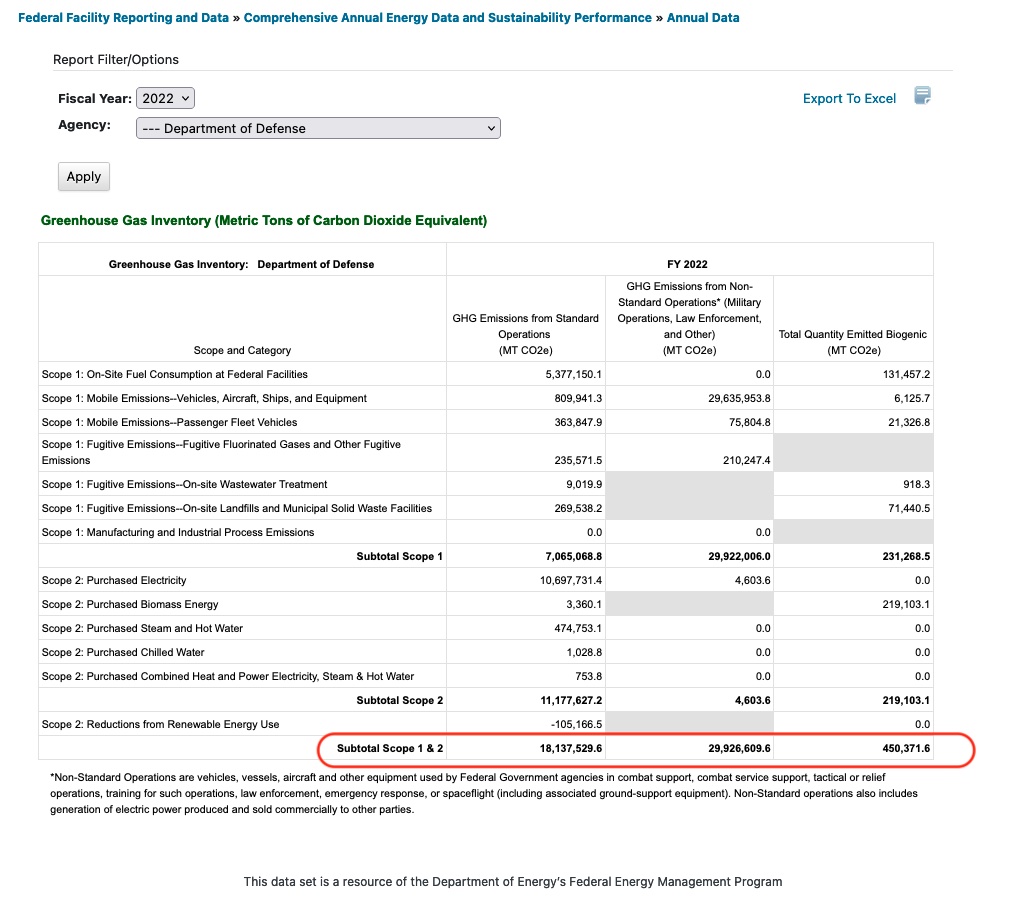

And then, on the matter of emissions, the portal gives us this:

Taking “Standard” and “Non-Standard” operations together, in 2022 the DOD emitted 48,065 Gigatons of CO2 in 2022. This is massive!

Brown University’s “Costs of War” project has produced some great work on the environmental costs of war, e.g. here. But very few antiwar activists have systematically worked to explore and publicize the many connections between warmaking and war preparing, on the one hand, and extreme environmental degradation on the other. One organization that has done this is Environmentalists Against War, which maintains a helpful (though somewhat dated-looking) website. Another is CodePink, which has maintained a pretty feisty “War Is Not Green” campaign for some time. But we probably also need a much bigger, more active, and well-funded organization that’s dedicated solely to presenting up-to-date news about the links between militarism and the climate crisis— and also, crucially, to doing intensive outreach to leaders and members of all strands of the broad environmental movement.

War, indeed, is not green at all. Let’s sing that from the rooftops and have the slogan adopted as broadly as possible.

… And the same is true for all three of the other issue-areas that I identified above. It should certainly be possible for the antiwar movement to build strong links with counterparts in the (anti-) gun violence, racial justice, and economic justice movements. But it strikes me that doing the work with the environmental movement would be a good place to start.