Pres. George H.W. Bush opens the 1991 Madrid Middle East Peace Conference

Last Thursday, Israel’s former ambassador to Washington Itamar Rabinovitch told a Council on Foreign Relations audience that he judged the then-current U.S.-Israeli focus on winning a Saudi-Israeli accord was badly conceived, inasmuch as it tried to bypass or paper over the Palestinian question. He likened the attitudes of Israeli and U.S. leaders to those of passengers on the Titanic, as they blithely sailed toward the large iceberg of the Palestinian issue that still lay very close to them…

36 hours later Hamas launched its Operation “Al-Aqsa Flood.”

That far-reaching and technically complex breakout took nearly all Israelis by surprise, and revealed the deep strategic complacency and tactical chaos into which Israel’s long-famed security system had fallen.

In most of Western discourse, the early reactions to what happened October 7 followed these tracks:

- Stunned surprise and horror at images of the suffering of Israeli civilians

- Weirdly racist claims that “Hamas could never have been as smart as to organize something like this… So it must have been organized by Iran“

- Horror at and excoriation of Hamas’s actions, portrayed as so frequently as “targeting” Israeli civilians

- Urgent calls for Israel to respond very forcefully indeed to Hamas, with little or no recognition that any such response would involve inflicting great suffering on Palestinian civilians—and also, potentially, on some of the dozens of Israelis now held captive within Gaza

- Repeated avowals that Hamas “must be punished”, accompanied by some unsubstantiated claims that the violence it showed during the October 7 breakout was “akin to that of the Islamic State.” (It wasn’t.)

- A general reluctance or refusal to link the October 7 breakout to the great suffering that Israelis have inflicted on Palestinians in Gaza, the West Bank (including East Jerusalem), Lebanon, and elsewhere for many decades now.

Who are Hamas?

In those Western media accounts, Hamas has nearly always been portrayed as intrinsically violent, deeply anti-Semitic, and unalterably opposed to the existence of Israel. But most of these descriptions are written by people who have never met, interviewed, or interacted with Hamas leaders. I have—periodically throughout the years between 1989 and roughly 2012. (You can find accounts of some of these interviews in The Nation, Boston Review, and elsewhere. E.g., here.)

Here is my current assessment of their positions and capabilities.

- Yes, Hamas is politically hard-line, in that its leaders have always strongly criticized the extent of the concessions that the leaders of the PLO/PA have been willing to make to Israel. We can recall that when Yasser Arafat and other PLO leaders reached the “Oslo Accords” for an interim agreement with Israel in September 1993 and then under those accords the PLO leaders “returned” to the occupied territories and there established the “PA” as an interim ruling body, Hamas strongly opposed that whole process. And in 1996, after the PLO/PA leaders held their first parliamentary and presidential elections in the occupied territories of the West Bank and Gaza, Hamas strongly opposed that electoral process, instead stepping up its violence against Israeli civilians.

- But it is also important to remember that that whole (heavily US-pushed) “Oslo process” that Arafat and the other PLO leaders had taken part in, led nowhere. Under Oslo, those leaders’ return to parts of historic Palestine in 1994 was supposed to inaugurate a five-year process of negotiation over a “final status” agreement with Israel. 1999 came and went with no final-status agreement. (And more recently, Washington has given up even any pretense of working for a final-status peace.)

- Meanwhile, throughout the 30 years since 1994, successive Israeli governments supported the continued building of—actually, quite illegal—Israeli settlements throughout the West Bank, including East Jerusalem, and have launched periodic, extremely damaging raids against Palestinian institutions in the West Bank and (especially) Gaza.

- In 2005, after the death of Yasser Arafat, the PA agreed, in coordination with the governments of Israel and the United States, to hold new elections for both its presidency and its “parliament” (both of them, institutions with tightly limited powers, under Oslo.) This time around, the Hamas leaders agreed to take part in the parliamentary election. That decision for the first time showed Hamas’s willingness to work within the Oslo framework—the clear goal of which was always understood by the PLO and all other Palestinian and Arab leaders to be the establishment of an independent Palestinian state alongside Israel

- These next PA parliamentary elections were held in January 2006. It soon became clear that Hamas had won them. They ended up winning 74 of the council’s 132 seats! In a reporting trip I made to the region soon thereafter I explored how Hamas had pulled that off that victory, which stunned the traditional (Fateh) leaders of the PLO and their backers in Washington and Tel Aviv. I found it was through exercising a combination of skills: a history of having provided helpful community services to different grassroots constituencies; a reputation for generally “clean hands” (unlike Fateh); effective organizing through women’s networks, with several Hamas women leaders getting elected to the parliament; and good electoral discipline, e.g., by not running more candidates than there were seats in multi-seat constituencies (as Fateh and its allies did in several places.)

- After the 2006 election, the PLO and its U.S. and Israeli allies started plotting to overthrow the newly elected leaders of the PA’s parliament and premiership, and in 2007 they tried to launch a violent coup to achieve that. The Hamas leaders in Gaza rebuffed that coup attempt. They then set about institutionalizing their position in Gaza (which has always been a key incubator for Palestinian nationalist networks), while the Fateh people retreated with their sometimes generous U.S. funding to Ramallah, in the West Bank. Hamas and its allies retained significant support in the West Bank and throughout the widespread Palestinian diaspora.

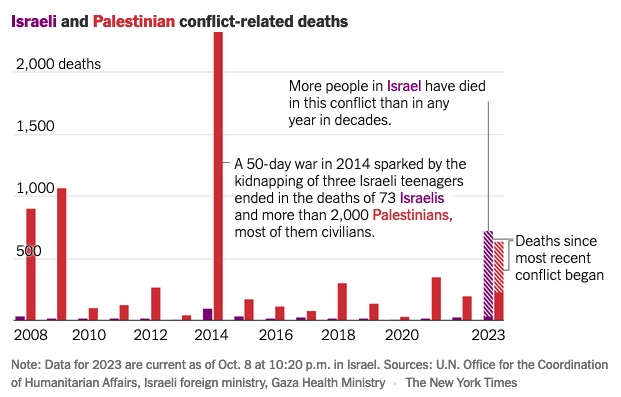

- Over the years since 2007, several Israeli government have undertaken very harsh punishment raids into Gaza—actions that many Israeli commentators refer to cynically as “mowing the lawn”, and that successive U.S. presidents have seemed generally happy to allow. The raids of late 2008 and summer 2014 were particularly destructive. This bar-graph that the NYT released late evening on October 8 shows the historic levels of casualties in Israeli-Palestinian fighting since 2008:

Hamas and the future of Palestine/Israel

Washington’s power within global politics has declined significantly since the time in the 1990s when it was easily able to hijack the whole broad, multilateral peace-negotiating system it had launched at the Madrid Peace Conference of October 1991. That conference was co-sponsored by the Soviet Union, which as we know collapsed shortly thereafter. So when some wily leaders from Israel’s staunchly Zionist Labour Party came to Bill Clinton’s Washington with their Norway-backed plan to “split off” the always-vulnerable and easily manipulable PLO from the other Arab parties who had been at Madrid, and to deal with them one-on-one, Pres. Clinton and his band of staunchly Zionist advisers thought that was a great idea…

Hence “Oslo” was born, as a very specifically U.S.-controlled project; and Washington has been able to monopolize control of all Palestinian-Israeli peace efforts since then.

In 2020, Pres. Donald Trump gave U.S. recognition to the Israeli government’s unilateral annexation of the Greater East Jerusalem area—which since 1949 had been considered an integral part of the West Bank—as well as its annexation of Syria’s Golan. Trump also backed away from giving even rhetorical support to the U.N.’s longheld position that there should be two states—one Arab and one Jewish—within the area of historic Palestine, preferring instead to sweep aside all the Palestinians’ claims and focus on the so-called “Abraham Accords” between Israel and some very distant Arab states.

After Joe Biden was inaugurated in 2021, he chose not to rescind Trump’s support for the two Israeli annexations, though the unilateral annexation of land held under military occupation remains a gross violation of international law (as does the implantation of one’s population as settlers into such lands.) And after initially voicing some inclination to work for a two-state solution in historic Palestine, over time Biden stepped away from that and shifted instead toward focusing on… the Abraham Accords.

But the global balance has shifted a lot since 1994. Washington can no longer effortlessly control all aspects of Arab-Israeli diplomacy. And other powerful voices in the international arena have retained their support for the two-state solution. In the past two days, China, Russia, and nearly all the Arab states (including Saudi Arabia) have reiterated their view that the two-state solution has to still be the international goal.

How realistic is this? People who question the viability of this goal tend to use one of two main arguments:

- That Israel will never agree to any solution that involves pulling out of East Jerusalem and the rest of the occupied West Bank the million or so settlers it has implanted in those areas since since 1967.

- That Hamas will always oppose the many Palestinian concessions that a two-state formula involves.

On this latter point, I contend there is non-trivial evidence, especially from the records of the 2005-06 electoral period in Palestine, that under some circumstances Hamas’s leaders might be persuaded to join a negotiation for a robust two-state outcome.

What do I mean by “robust”? I mean an outcome that would more or less return Israel to the frontiers it occupied 1949-67 and that goes a sufficient way toward allowing the ten million or so Palestinian refugees to exercise the “right to return or compensation” that they were promised by the United Nations back in 1949.

An early way to set the stage for this could be through a Security Council resolution that would (a) reiterate the UNSC’s support for its earlier resolutions 242 and 338, which stressed the inadmissibility of the acquisition of territory by force; and (b) reiterate the UNSC’s staunch opposition to all attempts to either implant settlers into territories held under military occupation or to annex such territories… As well as, of course, calling on all parties to forswear the use of violence and to abide by all the provisions of international humanitarian law.

Does it seem unrealistic to call for such a policy? Well, in many Western countries it may currently seem unrealistic because we have all become so inured, for many decades now, to Washington’s continued refusal to hold Israel to any decent international standards, and therefore also to Washington’s active (and generously funded) connivance in Israel’s campaigns of illegal territorial expansion and its frequent recourse to military violence and escalation.

But actually, in today’s world it is possibly much more unrealistic to expect Palestinians and their supporters and allies worldwide simply to give up any hope for a political path forward but to resign themselves forever to being rights-less Untermenschen.

Two weeks ago, at the U.N. General Assembly, Colombian President Gustavo Petro issued a potent call that,

the United Nations, as soon as possible, should hold two peace conferences, one on Ukraine, the other on Palestine, not because there are no other wars in the world – there are in my country – but because this would guide the way to making peace in all regions of the planet, because both of these, by themselves, could bring an end to hypocrisy as a political practice, because we could be sincere, a virtue without which we cannot be warriors for life itself.

This is a tremendous proposal, that touches on two major features of today’s international scene: first, that both these difficult conflicts, in Ukraine and in historic Palestine, need to be resolved through principles-based negotiations, and not through the continued application of force, and secondly that the crass hypocrisy with which the United States seeks to rally support against Russia in Ukraine while actively supporting Israel as it undertakes very similar actions in Palestine, needs to be called out.

Petro’s is thus a great proposal, and I would call on all Palestinian parties (including Hamas) and all peace-loving Israelis to endorse it.

And along the way, please let us forget about all that terrible, so-destructive “Oslo” process. Let’s get back to the principled and broad-based process of Madrid. But with a few key changes:

- Since there is no longer a Soviet Union, a new Arab-Israeli peace conference should be sponsored directly by the U.N. Security Council.

- This conference should not punt, as Madrid did, on the issue of Palestinian representation.

- The new conference should not (as the Madrid process did) allow itself to get distracted into numerous little byways of side-issues but should address the issues of sovereignty, political independence, and national boundaries head-on.

… And as for the challenges of pulling Israel’s settlers out of the occupied territories? Putting them in there was a clear policy of successive Israeli governments, and in many cases was funded by U.S. institutions. Let Israel and the United States figure out how to do the extraction—as France did with the one million settlers it had implanted in Algeria, or Portugal with its settlers in Angola or Mozambique… (As in those cases, if individual families want to stay and live in the newly independent state in peace, that could perhaps be discussed. But no more settler privilege.)

Thank you, as always, for this essential historical context.

Thank you Helena, I must say, having given up on the prospects of any viable two state solution, i found your article hopeful.

Good job

This is a great and pragmatic article, and is a breath of fresh air; but I wish to add two more items to the proposed solution:

1) that the city of Jerusalem should be an international city in accordance with the United Nation’s 1948 resolution, to assure protection and access to the Holy sites by all people, not just one or two.

2) Add importance and significance to the international city by moving the United Nations to Jerusalem since it is more acceptable and central to more countries of the world than New York city. This will help the economic future of Jerusalem considerably