Painting of the armistice negotiation in Compiègne, France, November 1917

The veteran Washington Post columnist David Ignatius started out life (as I did) as a reporter, and in today’s column he does a good job of portraying a spirited discussion he observed in Kyiv among Ukrainian politicians on whether and when to end the grinding conflict in their country. He describes one parliamentarian at that gathering, Oleksiy Goncharenko (also mis-spelled Gershenko) as “almost shouting” as he says,

“We all want everything. But this is the real world, and we must make decisions from real options. We don’t have unlimited time, and we don’t have unlimited people.”

Ignatius notes that earlier hopes that Ukraine’s summer counter-offensive might succeed “haven’t been realized”, and that “Ukrainians are now willing to talk more openly about ways to end the war than during my visits last year.” And he seems to be channeling the “painful” choice that he now sees confronting the Ukrainian leaders:

In just conflicts, the best strategy is surely to stay the course, especially when people begin to despair…

But if Ukraine seriously questions whether it can survive a fight that might take many years, then it needs to think about a way to freeze this conflict on its own terms — with a security guarantee from the United States as part of that deal.

Earlier in the piece, he had described parliamentarian Goncharenko as arguing that, instead of continuing to expel Russia from territories it has occupied since 2014, Ukraine “should seek security guarantees from NATO to protect the territory it holds.”

It’s very welcome that anyone in the U.S. corporate media—especially someone with the heft of a David Ignatius—is now talking about the possibility of “freezing the conflict” in Ukraine. But the implication that such a freeze should be pursued only in the context of Ukraine getting a “security guarantee” from the United States or from NATO is not at all helpful. Negotiating any such security guarantee would be a multi-year, very complex, and probably unsuccessful quest—all the more so, since one of the main reasons Russia has always given for its military action in Ukraine has been its deep concerns over NATO moving ever closer to its border.

But Washington does have a good alternative to pursuing that lengthy (and most likely, unattainable) goal of negotiating a longterm “security guarantee” for Ukraine. This alternative is an armistice—like the one that has kept the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) between North and South Korea more or less stable for more than 70 years now.

In an armistice agreement, no-one is required to give up their dearly held longterm goals. Instead of being required to do that, the parties to an armistice mutually agree to postpone discussion of their longterm goals to another stage of diplomacy; and they sketch out (and commit to) the process by which that will happen. Meantime, once the armistice is signed, the parties to the conflict stop their warmaking completely and fall back to positions that are an agreed distance from the front-line, under some agreed form of third-party monitoring mechanism.

And then, the communities on each side of the front-line can finally start to breathe, and to rebuild.

Ask the South Koreans (or North Koreans) if they’re glad that their armistice of 1953 went into place, or do they wish their leaders had continued fighting at that point for all the war goals they had at that time?

… When I was growing up in England, every November 11 we marked Remembrance Day, a way of remembering the 888,000 British men and the millions from other countries who had died in World War I. (The British dead included my only two great-uncles.) When I came to the United States, I was pleased to see that November 11 was commemorated explicitly as Armistice Day, and I wish it still were. An armistice, which is an all-fronts ceasefire that has monitoring mechanisms and a path to final-status peace negotiations built into it, is something well worth understanding and somberly celebrating.

Somehow, the value of that key tool from the diplomats’ toolbox has been forgotten in a United States that has focused so heavily on military dominance, military “solutions”, and military “interventions” for the past several decades.

David Ignatius ‘s latest column takes another mis-step, too, in addition to failing to point to the value of a seeking a speedy armistice for Ukraine. He concludes his column with this:

As a superpower, the United States can try to steer this conflict toward a settlement that protects Ukraine and doesn’t reward Russian aggression. But don’t ask Ukrainians to give up their cause. They won’t do it.

My response to that: Yes, going for an armistice is a great idea, precisely because it doesn’t require the Ukrainians or anyone else to “give up their cause” at this point.

But no, the United States can—and should—do a whole lot more to end this carnage than just “steering” it. (And the at-a-distance, hands-off approach that he implied there was even more clearly spelled out in his column’s title, which was, “A hard choice lies ahead in Ukraine, but only Ukrainians can make it.”)

Actually, no. If and when the U.S. leadership decides that this war needs to end, then Washington alone, or in conjunction with some chosen NATO allies, can negotiate an armistice agreement with Russia at any point. It doesn’t need to stay sitting in a back seat while allowing a Ukrainian leader (who may have his own mix of motivations) to drive the bus of this war over a cliff.

Again, ask the South Koreans.

Back in the early 1950s, South Korea’s U.S.-installed strongman Syngman Rhee definitely never wanted to negotiate anything with the communist-ruled north. But after Dwight Eisenhower became U.S. president, he speedily decided to nail down the armistice.

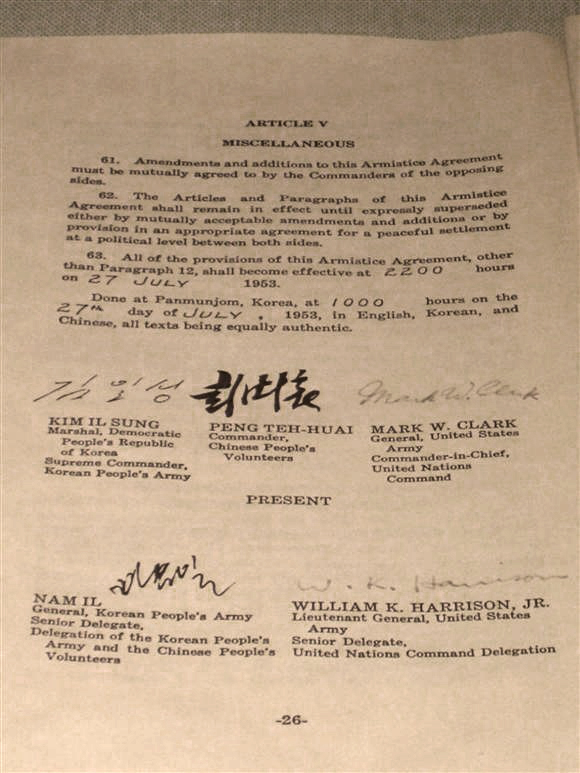

The armistice that was signed on July 27, 1953 in Panmunjom had three signatories: the local U.S. commander Gen. Mark W. Clark (who was also, by a quirk of history, representing the U.N. forces in Korea); North Korea’s Supreme Commander, Kim Il-sung; and the Commander of the “Chinese People’s Volunteers” who were fighting alongside the North Koreans.

Pres. Syngman Rhee never signed it. But over the years that followed, South Korea’s people benefited massively from the ending of the active conflict against their neighbors (and compatriots) to their north.

In 1953, Rhee had absolutely no realistic alternative but to “go along with” the terms of the armistice that Washington decided to commit to that year. And in Ukraine this year, Pres. Volodymyr Zelenskiy would have no realistic alternative but to “go along with” an armistice in his country, if Washington should decide that this is what needs to happen. (In Ignatius’s column, he quotes a Ukrainian defense ministry official as underlining that, “We depend 100 percent on the United States.”)

And yes, this armistice needs to happen, and needs to happen soon. The world needs it. The people of Ukraine need it. Americans need it. The madness of this war has to stop. And this wonderful, time-tested diplomatic tool of an armistice gives everyone a way to halt all the hostilities while deferring negotiations over “final status” matters to a later date.

Here in Washington DC, there seems to be great skepticism that Russia’s president would agree to any such halt. But that proposition has never been tested! Instead, Pres. Joe Biden and most of the congressional leaders just continue to stress their support for fighting against Russia “for as long as it takes.” But Ukraine’s people are hurting. They are weary and increasing numbers of them are now saying openly that it is time to end the fighting.

The rest of the world needs the fighting to end, too. And as we know, there are many visionary leaders around the world who are eager to help negotiate an armistice. Pres. Biden, get on the phone quick!

Thanks for this excellent essay

Yes, Helena, I couldn’t agree more with you. It is high time the Biden Administration returns to reality and ends its reprehensible effort to bleed Russia to the last Ukrainian.

My point would be that President Biden is standing in the way of an armistice because

he thinks that pushing such a plan would cause him to lose the election in the fall of 2024.

Putin’s support is dwindling. I think he would slowly be brought around to such a course

of action.