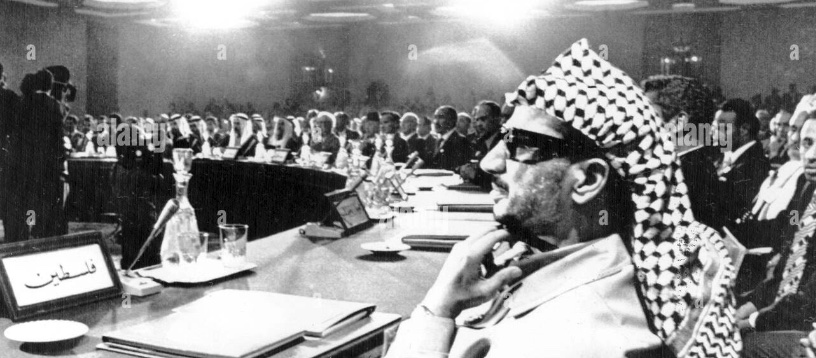

PLO leader Yasser Arafat taking part in the November 1974 Arab League summit

Most of the current commentary in the Western media on the 1973 Arab-Israeli war has focused on the “shock” effect the war had on Israel’s society and politics, or on the role the war played in jump-starting the Egyptian-Israeli negotiations that in 1978 led to the Camp David Accords, and a year later to the conclusion of a complete Egyptian-Israeli peace. (The recent release of a new Hollywood movie about Israel’s then-premier Golda Meir has helped keep the focus on the Israeli dimension of the war, though the historical accuracy of the movie has come under much serious questioning, e.g. here, here, or here.)

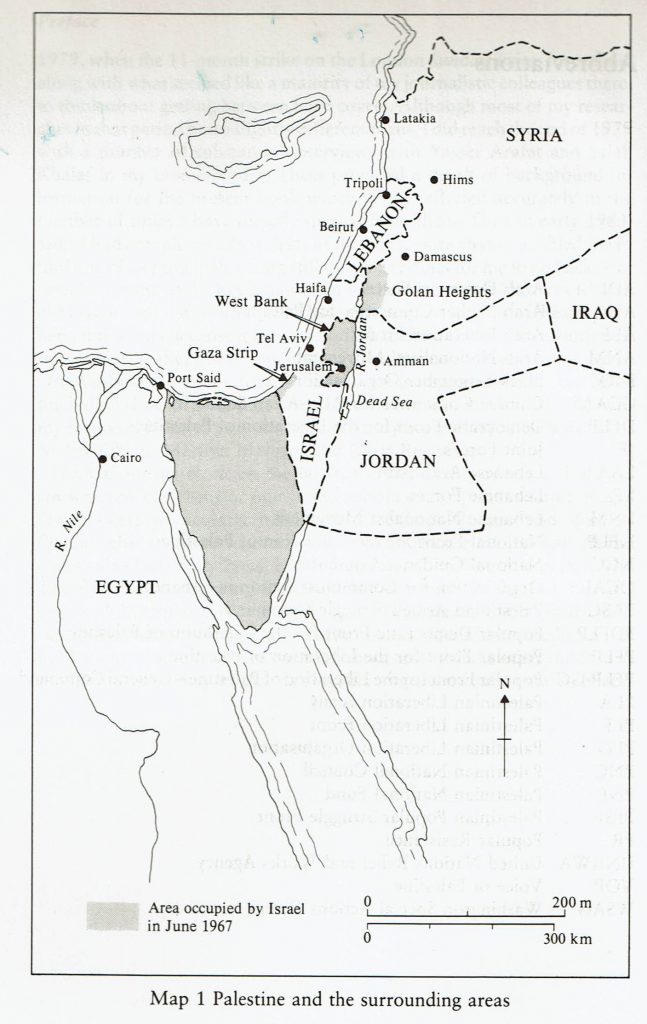

However, the Israelis and Egyptians were far from the only peoples in West Asia (the “Middle East”) whose fate was greatly impacted by the war. Indeed, given that Egypt was at that time far and away the weightiest of the Arab states, the fact that the war led to the launching of a diplomatic process that removed Egypt from the coalition of Arab parties that since 1948 had been in a state of unresolved war with Israel transformed the balance of power throughout the whole region.

The parties most direly affected by Egypt’s removal from the former Arab-rights coalition were firstly the always vulnerable Palestinians, and also the states of Syria (which had been a party to the war of 1973) and Lebanon, which had not.

In 1973, the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), which was the broadest Palestinian political movement, was still reeling from the defeat its guerrilla forces had suffered in 1970 and 1971 at the hands of the Jordanian monarchy. In that period, the Jordanian forces had brutally evicted the Palestinian guerrillas from Jordan. The PLO leadership and most of its constituent guerrilla groups then regrouped in Lebanon; and the PLO leadership retained considerable political heft in the region, still enjoying formal diplomatic ties with nearly all the other Arab governments.

During the 1973 war itself, a few hundred Palestinian fighters took part in the hostilities on the Egyptian front, and others took part, on the Syrian front. Salah Khalaf (Abu Iyad), who was the No.2 leader in the PLO’s largest constituent group, Fateh, also wrote later that on the day the 1973 war started, “some 70,000 Palestinian workers employed by Israeli enterprises went on strike in the West Bank and Gaza.”

Khalaf and his comrade in the Fateh leadership Farouq al-Qaddumi (Abul-Lutf) were both in Cairo in late summer 1973. In August, Egypt’s President Sadat gave them warning that the war would be coming soon, and on September 9 he explained that his main war goal was to jump-start the convening of an all-party peace conference to which the PLO would be invited along with Israel, all the front-line Arab states, the United States and the Soviet Union. (For more details on the role the PLO played during and after the war, see pp. 54-60 of my 1984 book The Palestinian Liberation Organisation: People, Power and Politics. Those pages can be downloaded here.)

The peace conference Sadat had been aiming for did indeed have a grand opening session in Geneva in December 1973. It brought together all the parties Sadat had told the Palestinian leaders that he wanted to see there– but with the exception of the PLO which was never invited. Then, over the two years that followed, first of all Sadat concluded a unilateral disengagement agreement with Israel (January 1974), then Syrian president Hafez al-Asad concluded one (May 1974)… and then Sadat concluded a second one (September 1975.) Through those actions taken by the two Arab protagonists in the 1973 war, it became clear to the PLO leaders that their movement and its cause was being shut progressively ever further out of the diplomatic action.

Meantime, in Lebanon, the proto-national infrastructure the PLO had been building up came under increasing assault from the Falangist-Christian militias there. In late April 1975, the Falangists launched a fierce assault against a busload of unarmed Palestinians, which ignited a broad civil war that raged throughout the country for many years. The Israelis were big instigators of (and beneficiaries from) that war, primarily through the alliances they built with the Falangists and other rightwing Christian militias.

In 1982, Israel’s defense minister, Ariel Sharon, launched a blisteringly broad military attack against the Palestinian and allied militias and the many Palestinian refugee camps in Lebanon. After six weeks of fierce fighting the Israelis were able to force the PLO to ship all its remaining fighting forces and its national leadership out of Lebanon to very distant shores (Tunisia, Yemen…) Very soon after that evacuation was complete, in September 1982 the IDF forces stood watch outside the two Palestinian refugee camps of Sabra and Shatila while fighters from their Falangist proxy forces went in and slaughtered many hundreds, perhaps thousands, of the unarmed Palestinian civilians residing therein. (The safety of those civilians had been explicitly guaranteed by the United States, as part of the PLO’s evacuation agreement.)

When he launched his attack on the PLO forces in Lebanon in summer 1982, Sharon did not need to worry about facing any counter-pressure from any of the Arab “front-line” states. Egypt was by then deep into the peace treaty that Sadat had concluded in 1979. Syria had abided since 1974 under an informally agreed “Red Line” agreement in Lebanon under which it and Israel each had a geographically separate “sphere of great influence” there. And Jordan’s King Hussein had acted in close concert with Israel’s leaders ever since the late 1960s.

…In total, then, the after-effects of the 1973 war were very negative for the Palestinians and their leaders in the PLO. The one tiny political gain they were able to make in the aftermath of the war came at the summit that the Arab League held in Rabat, Morocco in October 1974. At that summit, all the gathered Arab leaders– including Jordan’s King Hussein– agreed to a resolution that for the first time declared the PLO to be the “sole legitimate representative of the Palestinian people.” (They also resolved that the oil-rich Arab states … “would provide multi-annual financial aid to the [states in confrontation with Israel] and the PLO.”)

At the time, the PLO leaders, who were still smarting from their defeat at the hands of Jordan in 1970-71, were delighted to wrestle the “sole legitimate representative” card away from Hussein. He had, after all, been the leader who had lost East Jerusalem and the rest of the Palestinian West Bank region to the Israelis back in 1967. However, in the 49 years since October 1974, the PLO leadership has proven itself notably unsuccessful in winning any meaningful gains for the people whose “representation” they won at that time.

** One last note about Golda Meir. It should never be forgotten that she was the person who in 1969 stated outright that, “There was no such thing as Palestinians.”