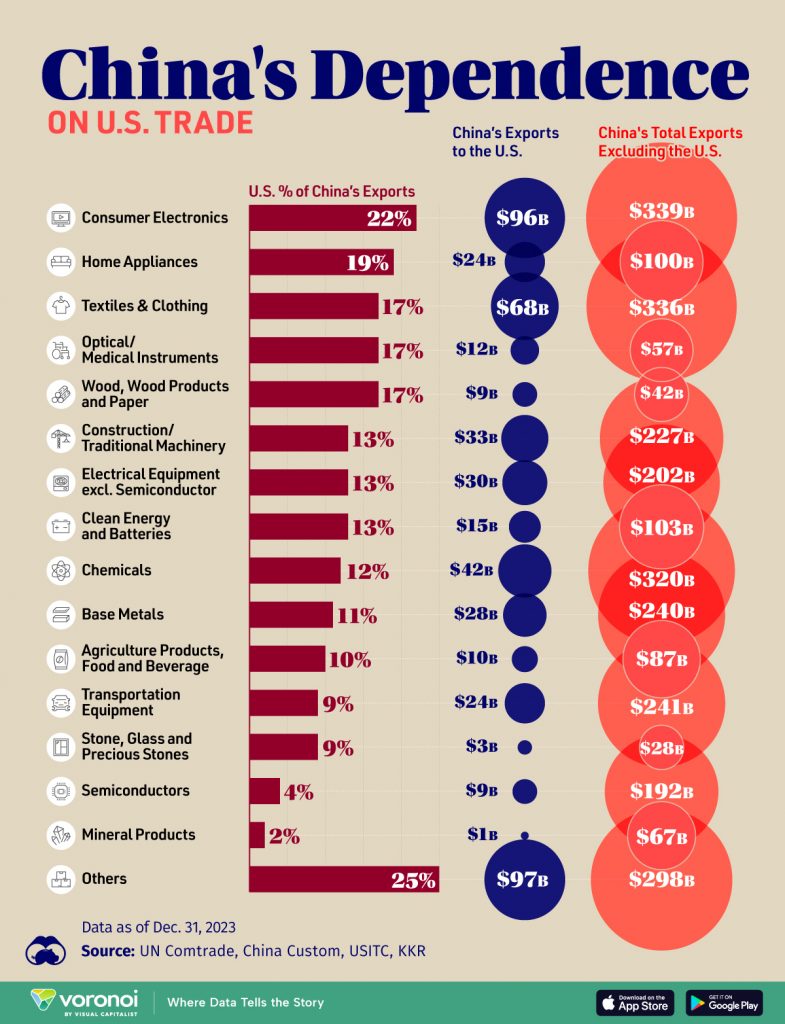

On April 2, Pres. Trump launched a super-harsh economic “war” against China, slapping on the country a harsh initial round of his tariffs that by April 9, after two rounds of reciprocal raises, had reached the level of 145%. By April 11, China’s reciprocals had reached 125%, and Beijing also announced a ban on exports of a broad range of rare-earth minerals and their derivatives.

Trump said throughout that he was waiting for China– and all the other countries on which, with extreme folly, he had also slapped tariffs of a range of harshness– to call him and start negotiating. Pres. Xi didn’t call. Trump blinked first and early, saying Oops he wanted to exempt computers and iPhones. But he also announced punishing new fees on all China-linked vessels to use U.S. ports.

Pres. Xi still hasn’t called, while there are several signs that Trump is increasingly eager to pick up the phone himself and start offering non-trivial concessions.

The two countries are thus far in an economic-warfare standoff that, as many participants in the IMF/World Bank’s Spring Meetings this week have warned, threatens to plunge the U.S. economy and a large chunk of the rest of the world economy into a deep recession.

I thought it would be a good time to take a deep dive into what China’s manufacturing and international-trading capabilities (and vulnerabilities) actually are…

But the journey I took in order to explore those topics took me to some extremely intriguing areas I had not expected when I first set out…

Snapshots of each side’s trade vulnerability to each other

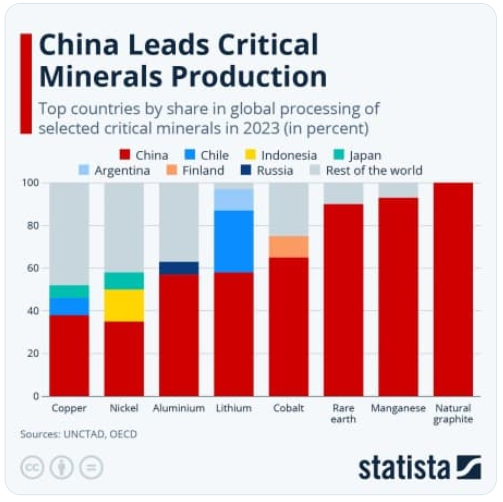

One really clear and simple resource I found on this basic topic was this report published (in English) by the Spanish daily El País, on April 11. The three most useful of the charts El País promised were these:

You can click on any of the images to enlarge it. The first chart shows the growth in the trade deficit, 2000-2024. The second shows the largest categories of goods in US imports from China, the top two of which are “Transmission equipment” ($55.5 bn) and “Computers” ($38.0 bn.) I’m guessing “transmission equipment” is electrical goods or inputs… The third chart shows the largest categories of goods in China’s imports from the U.S., with the three largest being Soya bean, Crude oil, and Petroleum gas.

(I’m not wholly convinced by the second of those charts, whose numbers seem far from adding up to the $439 bn of total U.S. imports from China. Nonetheless, the general picture is clear: U.S. exports are overwhelmingly raw or nearly-raw materials, while China’s exports are overwhelmingly manufactured products. But still.)

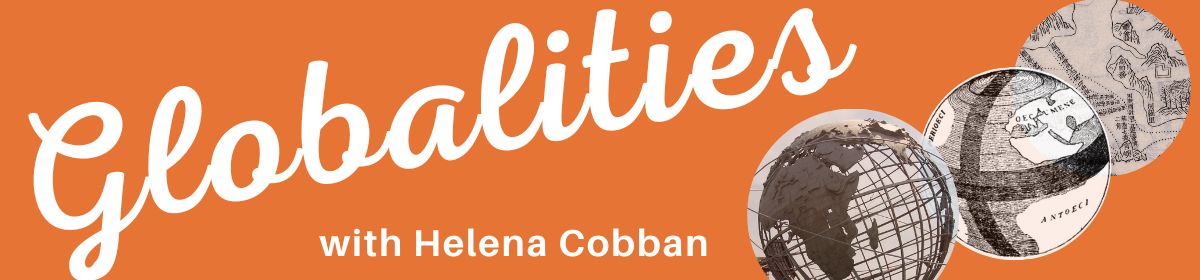

Another interesting question is the degree of dependence each country’s economy has on this bilateral trade. One interesting graphic for this is this one, from Visual Capitalist. (Click to enlarge, if needed.)

The only possibly misleading thing about this one is that it compares China’s exports to the U.S. in each category only to the country’s total experts, not to the total (export + domestic) consumption for these items in the year shown, which was 2023. And China’s domestic market in many of these categories is, as we know, very substantial. (Note to J.D. Vance: China’s population is certainly not made up of “peasants”. And guess what, they very much resented that racist put-down.)

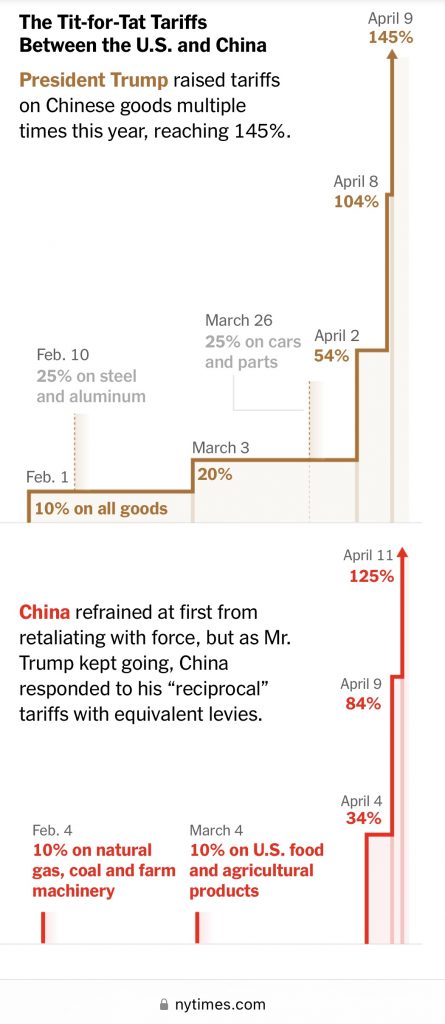

Just for comparison here, this chart shows the types of goods the EU was importing from China in 1995 and 2021…

So in 2021, the EU was importing $550 bn worth of goods from China, with 69% of those described as “Potentially ‘critical’ products.”

On Chinese manufacturing

I’ve been interested for some time in China’s advances in a broad range of technologies up and down the value chain. One of the high-tech analysts/commentators I’ve been following for a while is T.P. Huang. And this month, he has shared a lot of very informative material. Another Chinese-origin expert whose work I’ve come to appreciate only recently is William Huo, a guy who reportedly got his B.Sc. (or perhaps a graduate degree?) in Electrical Engineering and Computer Science from Princeton in 1984, then spent 30 months as Intel’s chief representative in China in the mid-1980s, and since 1992 has run his own company Cogent ATE in Beijing.

More on Huo, below. But first, T.P. Huang. This month, he has published three substantial threads, mainly in English, on Twitter/X.

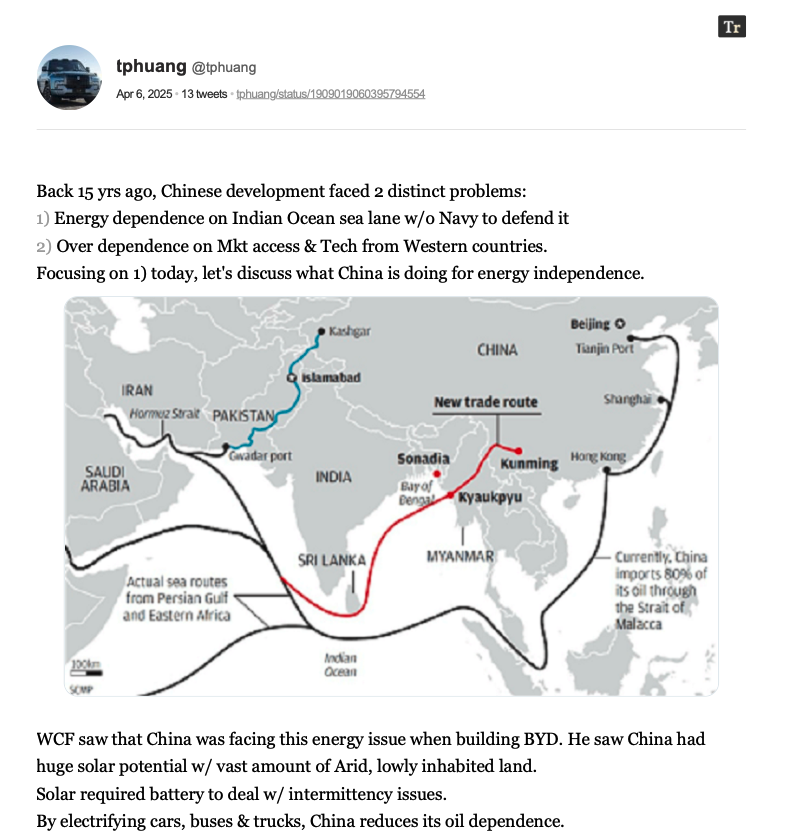

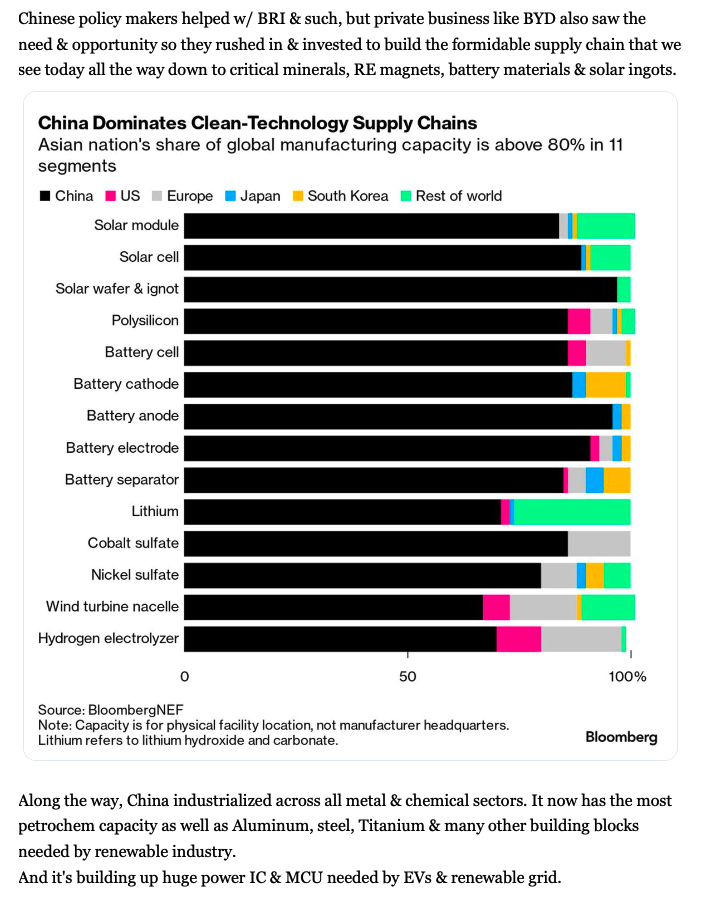

In the first of these, on April 6 (download PDF’s of Pt. 1, Pt. 2, Pt. 3) he tracked how, since 2010, China has pursued energy independence through a combination of developing its own green-energy production, storage, and transmission capabilities and developing more robust energy-importation routes.

Here’s the start of this lengthy and informative Twitter thread:

(WCF there is Wang Chuanfu, the founder of the electric-car company BYD.)

Here was just one of T.P.’s data-rich observations:

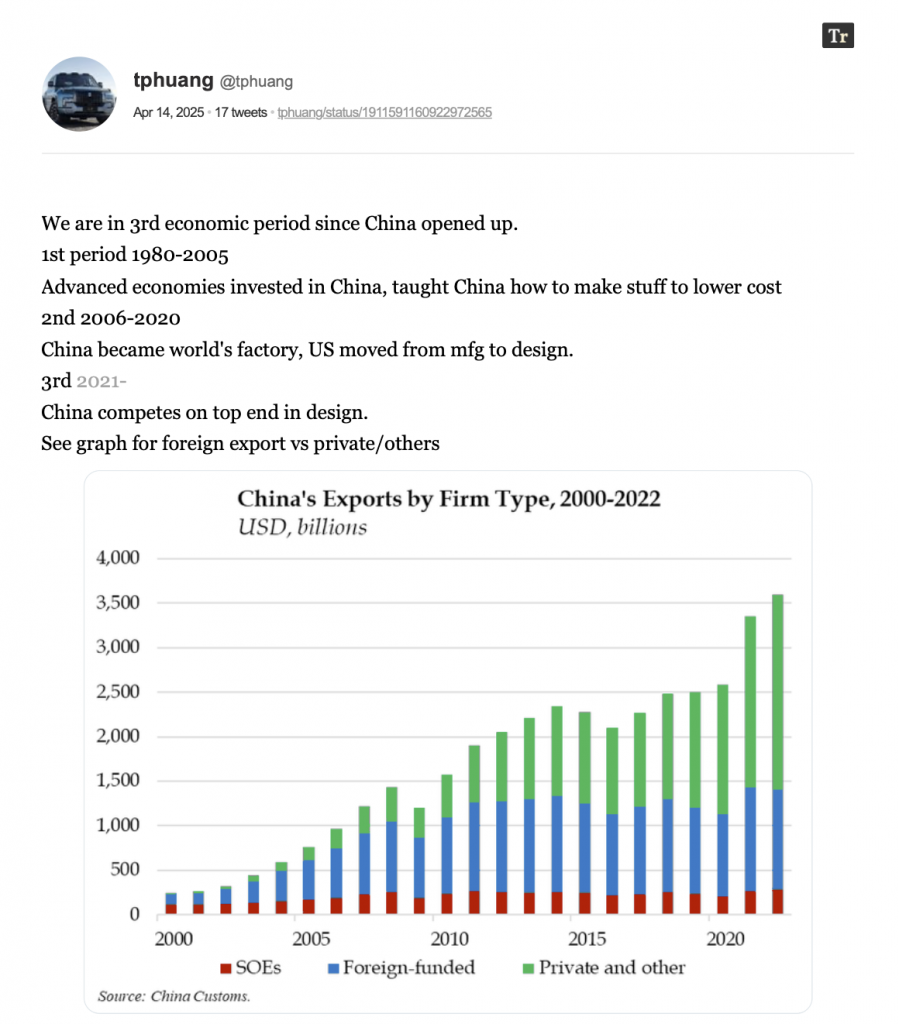

On April 14, T.P. published another informative Twitter thread (PDF here), in which he tracked how China had moved up the value chain in a range of different manufacturing sectors. This one started like this:

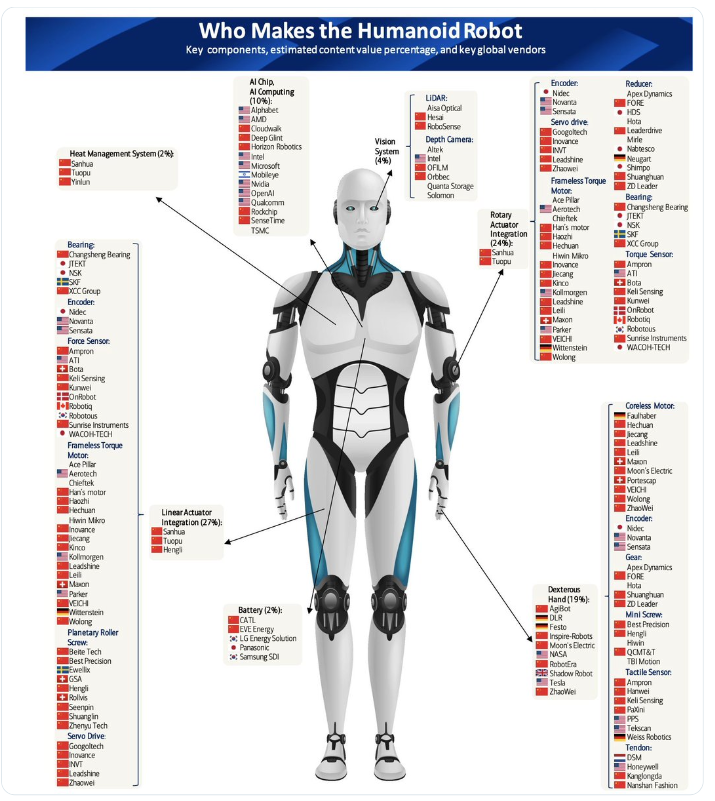

He has helpful graphs there on China’s rise in shipbuilding, vehicle production (and export), smartphone production, and other sectors, including development of humanoid robots and many kinds of automation.

(By the way, the NYT ran a great piece today on China’s very advanced development of robotics in manufacturing. The photos and videography there are all excellent.)

TP doesn’t give a source for this intriguing graphic he presented:

Some of his graphics are in English, some in Chinese. This one is in English, and well-sourced:

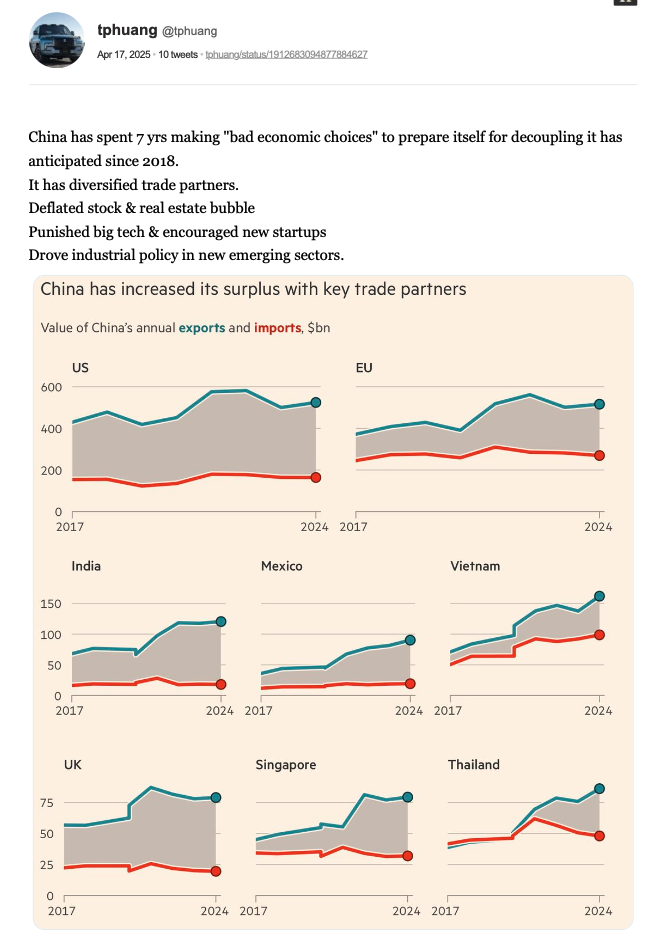

On April 17, as the many large shipping companies engaged in the US-China trade started to plunge into chaos, and as Trump ramped up his excoriation of China for having made “bad economic choices”, and as VP Vance– known by many in China as “the queen of eyeliner”– was making his racist and derogatory comments about China as being peopled only by “peasants”, TP composed another Twitter thread (PDF.)

This is how this one started:

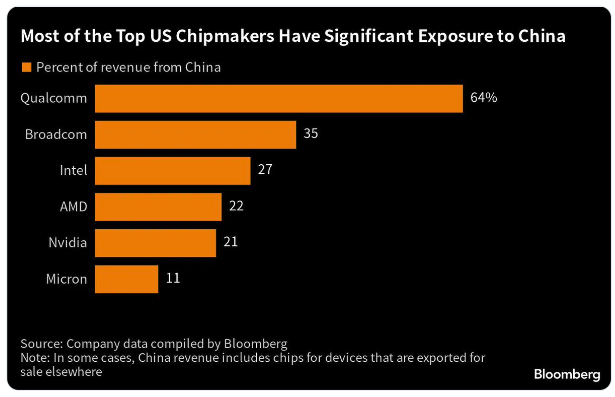

He provides this intriguing graphic from Bloomberg showing the vulnerability of US chipmakers to their markets in China:

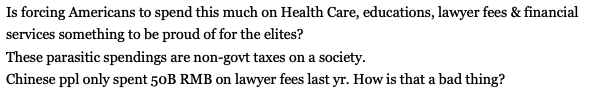

… And he concludes with some impassioned commentary:

(Copium, btw, is a handy portmanteau word for any narcotic you might take to help you cope.)

TP’s most recent Twitter thread (PDF) was a shorter musing on the contrast between the US and Chinese economic models. He used another graphic from the Visual Capitalist to illustrate the hefty proportion– roughly 2/3– of Americans’ spending that goes into services, and concluded thus:

In search of William Huo, an intriguing (& prolific) Twitter-thread author

So TP Huang’s shift from hard data to economic philosophizing makes a nice segue into the work of William Huo, a Twitter user who on January 24 announced the intentions he had set for the stream of Twitter threads he has produced in the Donald Trump era with a thread (PDF here) that started thus:

I noted a number of things there:

- the apparently approving citation of KMT leader Sun Yat-sen;

- the intellectual sophistication of the references to Adam Smith, Friedrich Hayek, neoliberalism, and Confucianism…

- and then, just the sheer discipline of how he composed that Twitter thread– and all the others of his that I’ve read.

I haven’t counted the characters in each individual tweet, but they almost certainly run under the limit that allows the writer to have the whole of his/her thought presented on the feed without Twitter resorting to visually annoying “jumps”. Huo’s tweets have vanishingly few typos or other observable errors. They’re composed in colloquial and hard-hitting English, with each tweet in the thread being posted within milliseconds of its predecessor. Each of his threads is composed as a response to either something someone else has tweeted, or something Huo has read elsewhere on the internet.

Plus, from the get-go– or rather, from the second in each series of tweets– they are all numbered as part of a (presumably previously conceived) whole thread: 1/10, 3/12, or whatever.

As someone who has played around with composing cogent short essays in the form of Twitter threads, I can say the discipline and focus Huo shows in his Twitter threads is mind-bogglingly impressive.

It was that discipline and sophistication of composition, as well as the speed and sheer rate of production of these Twitter threads– 18 well-composed threads just on April 23!– that led me to conclude, first, that these Twitter threads were actually being produced by a well-tuned AI system.

Initially I believed that, since these tweet-threads go out under William Huo’s name, he must at least approve the main thrust of their content? Then I came to wonder whether “William Huo” exists at all? Maybe he is just an avatar produced and run by some person or organization unknown?

If he is really, as his Xing profile presents him, the founder and long-time CEO of a (non-trivial), Beijing-based software or possibly AI company called Cogent ATE, then surely we should find more traces of his or his company’s real-life existence in generally well-sourced places like Wikipedia?

Who knows if he exists?

Anyway, whether “William Huo” is an actual person or an avatar for some shadowy intellectual body, the Huo output on Twitter is intriguing and thought-provoking. Here are some notable aspects of it:

- Huo’s threads go quite a lot deeper than TP Huang’s into some extremely nerdy hi-tech topics. For example, on April 23, he produced threads on Chinese advances in EV battery tech, new Chinese AI and robotics advances, Huawei’s new cluster processor, the development of a new Molybdenum disulphide transistor, and China’s inauguration of a “post-lithography” capability in chip fabrication. Nerd city! Clearly these breakthrough Chinese capabilities are things that someone in China– let’s call him “William Huo”– wants the English-speaking world to know about.

- His threads also go into the nuclear-tech (1, 2) and military (1, 2) arenas.

- He ventures with self-confidence into the arenas of economic history and economic philosophy. In particular, on April 23, he had a five-part series of Twitter threads reviewing the involvement of current U.S. Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent in the Asian Financial Crisis of 1997, and Bessent’s record since then. Definitely worth reading and bearing in mind, today… (1, 2, 3, 4, 5). Huo had also, earlier had an intriguing thread outlining, “How China Outplayed the West and Built the Future While America Decayed.”

- He ventures with confidence into fields of political philosophy (and geopolitics) in general. He recently had intriguing threads on: the rise of BRICS; how China outplayed the West; how China survived and thrived after the 1997 Asian Financial Collapse; the ravages of US neoliberalism in the 1980s; the Cultural Revolution as a (laudable) example of Confucian-style ritual annihilation; the myth of US wealth; the backwardness of US educational and tech sectors; and US “industrial policy” as cosplay…

- “Huo” (or whoever) had decided to share all these thoughts, data-points, insights, etc, in English, on Twitter. There is an evident, though carefully modulated, derision in his tone on occasion. (I have to confess I agree with just about all of the political philosophy he articulates.)

One footnote here, which may– or may not– also provide a clue to William Huo’s true identity (or anyway, the political leanings of whatever body lies behind his name) is that on April 22, Huo posted this fascinating Twitter thread about Jensen Huang, the founder of the advanced, US-based computer-chip company Nvidia.

Huo was working, there, to analyze Jensen Huang’s attempt to “thread” the needle on the always thorny topic of the status of Taiwan. Jensen Huang was born in Taiwan in 1962 and was sent to the U.S. with his brother, when he was nine. He went to college in Oregon, worked for various Silicon Valley companies, then in 1993 he co-founded the processor-design and -production company Nvidia. Its design concept was based on optimization for graphic processing, which proved to be a winning formula.

Today, Nvidia has become the biggest producer of chips for the US’s AI sector, and Huang is still at the helm. But China is also a big market for the company, so Huang, like the leaders of all the other big US chip companies, has had to figure how to deal with the yawning chasm of de-coupling that Trump has dug. The status of Taiwan is a complex issue for all the titans of the high-tech world, given that the world’s biggest producer of high-end chips is the Taiwan-located TSML. But for Huang, the status of Taiwan is also a personal issue…

So at a recent Trump-hosted dinner, Huang straightforwardly proclaimed that he had “grown up in China.”

Huo’s comment on that was that,

It wasn’t a mistake. It was a move…. This is what survival looks like at the top of the semiconductor food chain….

While the US struts around with tariffs and sanctions, Huang is speaking fluent multipolar reality.

He throws Washington a $500 billion bone, then tells Beijing Nvidia has grown thanks to Chinese partnerships.

Two masters. One strategy.

… Anyway, let’s see what happens in this potentially cataclysmic Trump-China standoff over the days to come…